Authors: Sophia Gorgens, MD (EM Resident Physician, Zucker-Northwell NS/LIJ) and Jessica Army, MD (EM Attending Physician, Zucker-Northwell NS/LIJ) // Reviewed by: Michael J. Yoo, MD (EM Attending Physician, San Antonio, TX); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 35-year-old man with a history of inflammatory bowel disease presents to emergency department (ED) with 2 days of abdominal pain. The pain is not localized, fluctuates in severity, and does not radiate. He endorses worsening nausea, vomiting, and anorexia over this time. His last bowel movement was 2 days ago and denies melena or hematochezia. His surgical history is significant for an appendectomy 5 years prior and a cholecystectomy 2 years prior. On exam, he is pale and diaphoretic, and his abdomen is diffusely tender with guarding. His vital signs are: heart rate 110, blood pressure 92/60, and temperature 99.6°F. Although you are concerned for a small bowel obstruction, the patient’s vital sign abnormalities are suspicious for a complicated obstruction. What are your next steps in management?

Introduction

Perforated hollow viscus is the dreaded complication of bowel obstruction, often resulting in sepsis and peritonitis, with a mortality rate reaching 30-50%.1 In particular, closed-loop obstruction and strangulated obstructions are at greater risk for perforation.2 There are many additional causes of bowel perforation, including trauma, foreign body ingestion, diverticulitis, inflammatory bowel disease, stercoral colitis, peptic ulcer disease, ischemia, and cancer.3-6 Although some causes present more insidiously than others, their prognoses are similar. Subsequently, early recognition of patients at high risk for perforation, prompt workup, appropriate management, and emergent surgical consultation is essential to prevent mortality in patients with perforated hollow viscus.

Risk Factors, Signs, and Symptoms

Patients with a history of abdominal surgery, radiation therapy, inflammatory bowel disease, or colon cancer are at increased risk of both bowel obstructions and perforation.1-2,5-6 Specifically, the development of adhesions, anatomical changes from prior surgeries, tumors, and any chronic inflammatory process makes patients vulnerable for the development of complicated bowel obstruction. Additionally, bowel perforations present similarly to bowel obstructions, with patients often experiencing nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, and abdominal distension.1,2,5-9 On physical exam, patients may have localized or diffuse abdominal tenderness, often with guarding and may have either hyperactive bowel sounds (in early-stage bowel obstruction) or diminished or absent bowel sounds (in late-stage bowel obstruction).1,2,5,7-9 Although classically associated with bowel ischemia, pain out of proportion on exam may be found in patients with perforation.2 Furthermore, signs of sepsis and peritonitis, including fever and leukocytosis, are not uncommon in patients with viscus perforation.1,5,8 However, hemodynamic instability such as hypotension and tachycardia, can be absent, and patients may appear deceptively stable in cases of delayed presentations.5,7

ED Workup

Serum laboratory studies are generally non-specific for patients with bowel perforation but can be a helpful guide for resuscitation and optimization for surgical intervention. Patients should be considered unstable and in need of rapid resuscitation and likely emergent surgery if they have hemodynamic instability, pH <7.2, base excess < -8, or evidence of coagulopathy.7,8

In a patient with high suspicion for a perforated viscus, the first imaging to obtain is an upright abdominal X-ray. Abdominal X-rays are good screening tools due to its easy accessibility and low cost. Although abdominal X-rays can quickly detect perforation, they only have a sensitivity of 66-85% and may be nonspecific.2,5-7,9 The most common finding for perforated viscus on X-ray is free air under the diaphragm, but this can be absent if there is a minimal amount of free air or if the patient is lying down (due to patient condition) rather than standing upright (Figure 1).2,5

Figure 1. An anterior-posterior upright abdominal X-ray demonstrating free air under the left hemidiaphragm concerning for hollow viscus injury (white arrow).12

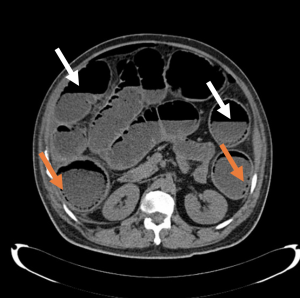

The sensitivity and specificity of computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen and pelvis for bowel obstruction approach 100% but their ability to detect complications such as perforations is lower (Figure 2).2,9 Though considered the gold standard, CT only identifies the site of perforation 82% to 90% of the time.4 Subsequently, frequent reassessments, serial abdominal exams, and considering the patient’s overall clinical status is essential in patients with any obstructive process—new hemodynamic instability or peritonitis may suggest the development or worsening of bowel perforation despite the lack of radiographic evidence on CT. Furthermore, up to 24% of small bowel obstructions require surgical intervention, either from the development of complications or failure of medical management, and obtaining CT imaging from the ED may help with operative planning.3,7-9

A CT with IV contrast is preferred over oral or rectal contrast, especially as nauseous and vomiting patients often cannot tolerate oral contrast.3-6,8-9 In the setting of bowel obstructions or perforations, the literature is sparse comparing the different contrast modalities (IV, oral, or rectal contrast). However, one meta-analysis showed no difference in identifying perforation when IV and oral contrast were compared, though this study was performed in patients with perforation secondary to blunt abdominal trauma.10 If oral contrast is used, water-soluble contrast is preferred in case of contrast extravasation.3,4

Although free air is highly suspicious for perforation, more subtle findings of bowel perforation with or without concomitant free include localized foci of extraluminal air, mesenteric fat stranding, bowel wall thickening, extraluminal fluid, extraluminal abscess, oral contrast extravasation, and bowel wall discontinuity (Table 1).3,4 Additionally, free air can be found intraperitoneal, retroperitoneal, or extraperitoneal, and its location further helps elucidate the area of perforation along the bowel in unclear cases, which is useful for surgical planning.4

Table 1. Summary of radiographic findings of bowel perforation on CT.3-4

Figure 2. Axial slice of a non-contrasted CT of the abdomen demonstrating air-fluid levels (white arrows) and multiple foci of intramural air (orange arrows).12

Several conditions can mimic the radiographic findings of perforation on CT. Specifically, patients with recent abdominal surgery will have postoperative pneumoperitoneum for an average of two weeks; infections such as emphysematous pyelonephritis or emphysematous cholecystitis will have foci of air; barotrauma, pneumothorax, or pneumomediastinum may track air between the abdominal wall and peritoneum.3-4 While this list of differential diagnoses are not inclusive, they highlight the necessity of an accurate history and physical exam to help correlate clinical suspicion with radiographic data.

Alternative imaging modalities include magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), which is generally more expensive and less available in the ED, and bedside ultrasound. Ultrasound is user dependent but has specificity of 84-100% and a sensitivity of 83-97% for recognizing small bowel obstructions (SBO). However, complications such as perforation may be harder to identify on ultrasound.2,5,9,11

Management

In uncomplicated small bowel obstructions (SBO), medical management to include antiemetics, analgesics, electrolyte optimization, and bowel rest can often resolve the obstruction. Additionally, a nasogastric (NG) tube may decompress the stomach and reduce the patient’s symptoms.2 There has been much debate about the usefulness of NG tubes in SBOs, but there is a paucity of data regarding NG tubes for bowel obstruction or perforation.2,13 The insertion of NG tubes for symptomatic patients, particularly those with active vomiting and abdominal distension, may be a reasonable strategy.8,13

In any patient with an obstructive process, fluid resuscitation with balanced crystalloids such as lactated ringers (LR), correction of acidosis if present, pain and nausea control, and electrolyte optimization is necessary.2,5,7,14 Unfortunately, data regarding specific fluid administration (liberal, restrictive, or goal-directed) are limited, especially in patients undergoing abdominal surgery, and the patient’s clinical status should dictate fluid management.14 Unlike uncomplicated obstructions, however, bowel perforation requires emergent surgical consultation for operative repair.2 Broad-spectrum antibiotics should also be started early, ideally covering Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria.2 Any size injury to the gut mucosa (edema, perforation, ischemia) can result in the translocation of intestinal microorganisms, and with large defects, frank fecal spillage into the peritoneum.7 Therefore, even if a patient does not appear septic, prophylactic antibiotic coverage of Gram-negative and anaerobic bacteria should be given.7 Specifically, clinicians should cover for Enterobacteriaceae, Klebsiella, and Enterococcus, with the additional coverage of Staphylococcus (including MRSA) and Pseudomonas in patients with recent instrumentation or hospitalization. Strategies include piperacillin-tazobactam 4.5g as a loading dose with 3.375g given every 8 hours, ertapenem 1g q24h, or metronidazole 1g q12h + ciprofloxacin 400mg q8h. The addition of vancomycin 20mg/kg can be added to cover MRSA, if necessary.15

Case Resolution

The patient’s rectal temperature revealed fever to 101.2°F. After receiving 2 liters of LR as well as acetaminophen and morphine, the patient’s vitals improve to HR 95, BP 115/70, and temperature 98.8°F. Recognizing sepsis, you start empiric piperacillin-tazobactam and draw blood cultures and labs, which return with a white blood cell count of 22. As the patient is too weak to stand, his supine chest and abdomen x-rays are unremarkable, but the subsequent CT abdomen pelvis with IV contrast shows a perforated small bowel obstruction. Surgery is consulted, and the patient is admitted for an operative repair of his bowel perforation in the OR.

Key Points

- Abdominal X-rays or ultrasound are fast and easy screening tools and can help diagnose patients who need emergent surgery for bowel perforation. However, they can be falsely reassuring and can miss cases of subtle pneumoperitoneum.

- A CT with IV and not oral contrast is the preferred imaging modality, especially as nauseous and vomiting patients often cannot tolerate oral contrast.

- Beware of bowel perforation mimics on CT scan, including postoperative pneumoperitoneum. Post-operative patients can also be at risk of perforation and pose challenges in delineating expected post-operative air versus perforation. In these cases, clinical correlation with the patient’s symptoms and vital signs and early surgical consultation is recommended.

- Remember to optimize medical management before the OR, including giving fluid resuscitation and antibiotics to cover Gram negative and anaerobic bacteria. Choices include piperacillin-tazobactam or a carbapenem (i.e. meropenem), though lower risk patients can still be covered by the combination of ceftriaxone and metronidazole.

References and Further Reading

- Aubuchon, Thomas et al. “EM@3AM: Viscous Perforation.” EMDocs. 2019 Dec. http://www.emdocs.net/em3am-viscous-perforation/

- Long B, Robertson J, Koyfman A. Emergency Medicine Evaluation and Management of Small Bowel Obstruction: Evidence-Based Recommendations. J Emerg Med. 2019;56(2):166-176.

- Borofsky S, Taffel M, Khati N, Zeman R, Hill M. The emergency room diagnosis of gastrointestinal tract perforation: the role of CT. Emerg Radiol. 2015;22(3):315-327.

- Kothari K, Friedman B, Grimaldi GM, Hines JJ. Nontraumatic large bowel perforation: spectrum of etiologies and CT findings. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42(11):2597-2608.

- Cutright, Amy et al. “Perforated Viscus.” SAEM. 2019. https://www.saem.org/about-saem/academies-interest-groups-affiliates2/cdem/for-students/online-education/m4-curriculum/group-m4-gastrointestinal/perforated-viscus

- Jaffe T, Thompson WM. Large-Bowel Obstruction in the Adult: Classic Radiographic and CT Findings, Etiology, and Mimics. Radiology. 2015;275(3):651-663.

- Pisano M, Zorcolo L, Merli C, et al. 2017 WSES guidelines on colon and rectal cancer emergencies: obstruction and perforation. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:36. Published 2018 Aug 13.

- Bower KL, Lollar DI, Williams SL, Adkins FC, Luyimbazi DT, Bower CE. Small Bowel Obstruction. Surg Clin North Am. 2018;98(5):945-971.

- Rami Reddy SR, Cappell MS. A Systematic Review of the Clinical Presentation, Diagnosis, and Treatment of Small Bowel Obstruction. Curr Gastroenterol Rep. 2017;19(6):28.

- Lee CH, Haaland B, Earnest A, Tan CH. Use of positive oral contrast agents in abdominopelvic computed tomography for blunt abdominal injury: meta-analysis and systematic review. Eur Radiol. 2013;23(9):2513-2521.

- Kuzmich S, Burke CJ, Harvey CJ, Kuzmich T, Fascia DT. Sonography of small bowel perforation. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2013;201(2):W283-W291.

- Morgan, M., Saber, M. Bowel Perforation. Reference article, org. (accessed on 09 Oct 2021) https://radiopaedia.org/articles/56677

- Morgenstern, Justin. “NG tubes for small bowel obstruction: More pain than evidence.” First10EM. 2021 Aug. https://first10em.com/ng-tubes-for-small-bowel-obstruction-more-pain-than-evidence/

- Casey JD, Brown RM, Semler MW. Resuscitation fluids. Curr Opin Crit Care. 2018;24(6):512-518.

- Tan A, Rouse M, Kew N, Qin S, La Paglia D, Pham T. The appropriateness of ceftriaxone and metronidazole as empirical therapy in managing complicated intra-abdominal infection-experience from Western Health, Australia. PeerJ. 2018;6:e5383. Published 2018 Aug 15.