Author: Shane O’Donnell, DO (EM Resident Physician: UTSW – Dallas, TX); Zachary Aust, MD (Assistant Professor of EM/Attending Physician: UTSW – Dallas, TX) // Reviewed by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 30-year-old male presents to the ED after being the operator of a public-access electric scooter while at night and accidentally driving full-speed into an unmarked pothole. He remembers falling directly onto the handlebars and coming to a complete stop. He called EMS when he realized it hurt too much to stand up. He denies loss of consciousness, is not on any blood thinners, and currently complains of pain in his hips/groin.

Initial assessment on arrival includes vital signs BP 134/86, HR 94, RR 16, SpO2 98% on room air, and temperature 99.0F. He is speaking and mentating appropriately but in significant discomfort when you exam his pelvis. Blood is seen at the urethral meatus, and the pelvis is unstable. There is no obvious perineal ecchymosis at this time. The rest of the exam is unremarkable.

What type of injury should be considered with blood at the urethral meatus and suspected pelvic fracture?

Answer: Bladder Rupture

Background:

- The bladder is a hollow organ adjacent to the pelvic floor, situated posteriorly to the pubic ramus, anterior to the uterus in women, and anterior to the rectum in men.

- It is a primarily extraperitoneal organ. The dome of the bladder is lined by the peritoneum and is also the weakest part of the structure.

- Bladder injuries are uncommon, occurring in approximately 1.6% of blunt trauma.1

- Injuries are primarily caused by blunt trauma and are most often associated with pelvic fractures. Penetrating trauma and iatrogenic injuries do occur but are much less common.2

- Motor vehicle accidents account for the overwhelming majority of bladder rupture presentations.3

Physical Exam

- Physical exam findings may not be conclusive and the absence of abnormalities on exam should not be used in solidarity to rule out bladder injuries.

- Pelvic instability should raise your suspicion of a bladder injury, as pelvic factures are the most common associated injury with bladder injury.4

- Blood at the urethral meatus/gross hematuria is an important finding and should also raise your suspicion for bladder injury (Sensitivity: 90%).4

- FAST exam is not sensitive enough to reliably detect solid organ injury, including bladder injury (Sensitivity 41-44%).5, 6

- In delayed presentations, signs of peritonitis and/or ileus may be evident if urine is extravasating into the peritoneal cavity. This is often due to the vulnerability of the bladder dome and it’s anatomic location adjacent to the peritoneal cavity.6

Evaluation

- Gross hematuria, especially with a pelvic fracture, increases suspicion of injury along the GU tract, and coinciding urethral injuries must also be suspected. Therefore, a retrograde urethrogram (RUG) should be performed prior dedicated imaging for bladder injury.

- To perform a RUG: Obtain a baseline KUB. After, insert a foley catheter a few centimeters into the urethra and gently inflate the balloon until a snug fit is achieved. Avoid overinflation and iatrogenic urethral injury. Instill 50-60mL of water-soluble contrast and obtain a second KUB while the last 10-15mL are being infused. Look for contrast extravasation as a positive finding for urethral injury.

- A RUG is NOT a substitute for dedicated cystography.

- Pelvic fracture alone is not an absolute indication for dedicated bladder imaging.7

- Gross hematuria + pelvic fracture = absolute indication for evaluation of bladder injury.

- Microscopic hematuria + pelvic fracture = consider bladder imaging studies / urologic consultation especially if other concerning signs are present.8

- Inability to void

- Increased BUN & creatinine

- Suprapubic pain

- Low-density peritoneal fluid

- Penetrating injury with pelvic trajectory + hematuria (gross or microscopic) requires radiologic or surgical evaluation.

- All life-threatening injuries should be identified and stabilized prior to evaluation of bladder injuries. This may require repeat imaging.

- Cystography is the gold standard for evaluation of bladder injury. Plain film and CT cystography both have sensitivities of 95%.9,10

- Empty bladder of urine using foley catheter.

- Instill a dilute, water-soluble contrast until the patient feels the need to urinate or until you have injected >300mL of contrast.

- CT slices should be thin cuts. Check with your institutional protocols for ordering.

Management/Disposition

- Urology consultation is necessary for all cases of confirmed bladder injury.

- Intraperitoneal Bladder Injury

- Communication between the bladder and peritoneal cavity can lead to urine extravasation into the peritoneal cavity, progressing to peritonitis and possibly sepsis.

- These injuries will almost always require surgical intervention, as they do not often heal spontaneously and can have devastating outcomes in left untreated.13

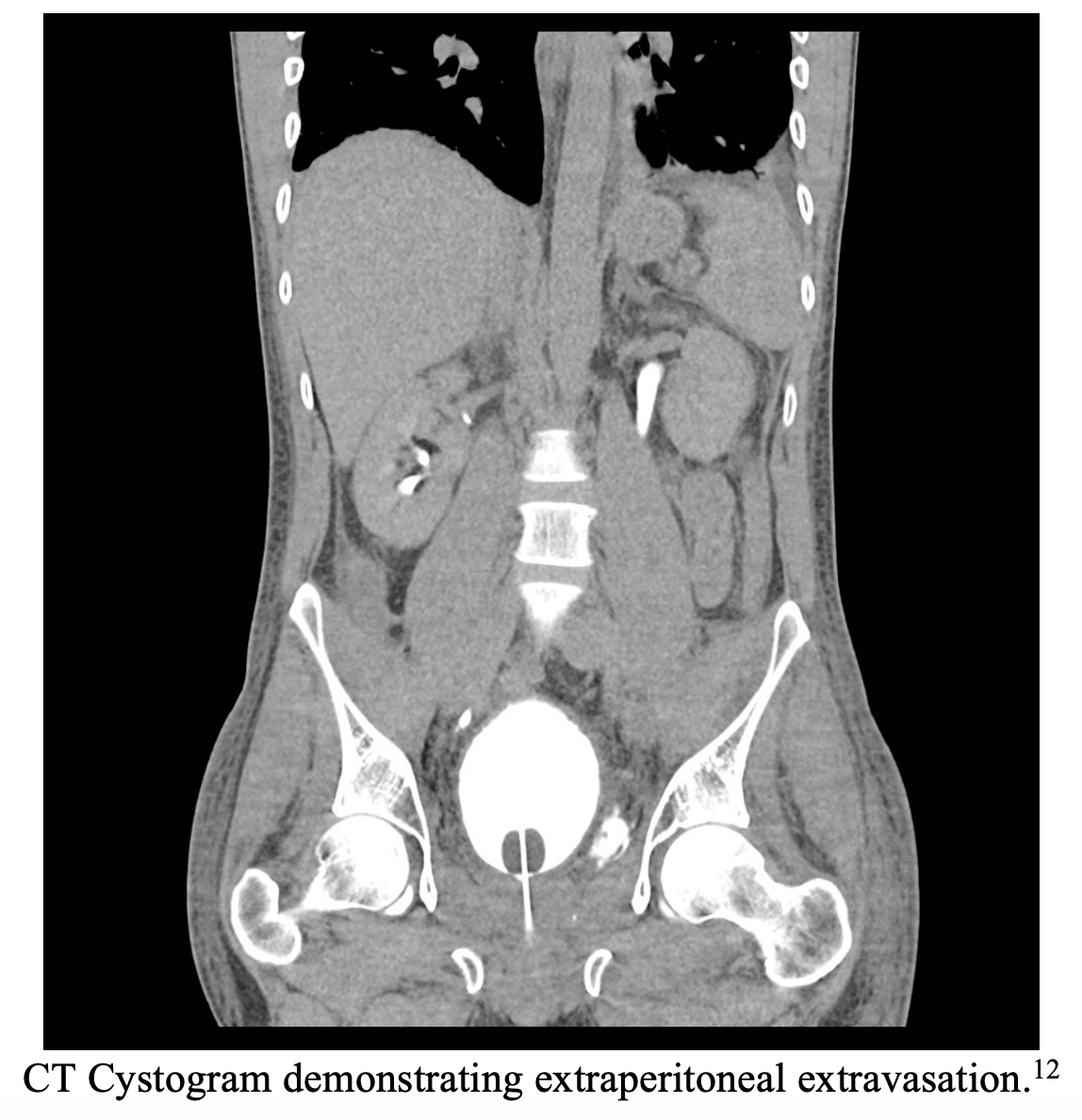

- Extraperitoneal Bladder Injury

- Can often be managed conservatively with foley catheter drainage for 2+ weeks.13,14

- May require surgical repair in the setting of complex injuries in the surrounding area.13

- Open pelvic fracture.

- Associated rectal or vaginal injury.

- Bladder neck injury.

- Foley catheter drainage issues from persistent hematuria / blood clots.

Pearls

- Gross hematuria alone OR pelvic fracture + hematuria is an indication for evaluation of a bladder injury.

- Identification and stabilization of life-threatening injuries should take place prior to dedicated bladder imaging.

- Performing a RUG to evaluate for urethral injury is NOT a substitute for cystography.

- CT and Plain Film cystography and almost identical sensitivities and specificities.

- Bladder injury location will guide surgical vs conservative management.

Post MVC, the restrained passenger of an automobile presents to the ED with lower abdominal pain. There is blood at the urethral meatus. A FAST examination is negative for free fluid in the abdomen. Vital signs are stable. A CT scan of the abdomen-pelvis with CT cystography is thus obtained, revealing an extraperitoneal bladder rupture and fractures of the left inferior and superior pubic rami. Which of the following should be part of the management plan for this patient?

A) Admission to the trauma service for continued observation

B) Application of a pelvic binder

C) Immediate consultation to urology for placement of a suprapubic catheter

D) Surgical repair of the bladder rupture within 24 hours

Answer: A

Greater than two-thirds of bladder injuries result from blunt trauma. Most occur from motor vehicle collisions, with severe abdominal injury such as that which occurs with ejection from the vehicle or excessive compressive force from the seat belt on a distended bladder. Bladder injuries are classified as contusions, intraperitoneal ruptures, extraperitoneal ruptures, or a combination of intraperitoneal and extraperitoneal ruptures. The management of extraperitoneal bladder rupture is nonsurgical with Foley catheter urine drainage for one to two weeks to allow for spontaneous healing (assuming urethral injury has also been ruled out). None of the injuries sustained by this patient require an emergent procedure. However, given the reported mechanism and associated findings, it is reasonable to admit the patient for observation, serial exams, and urology consultation.

A pelvic binder (B) is used to reduce venous bleeding caused by sacroiliac joint disruption in open-book pelvic injuries; pubic rami fractures are considered stable and do not require such intervention. Insertion of a suprapubic catheter (C) is unnecessary in the management of extraperitoneal bladder rupture. In fact, the treatment is usually limited to Foley catheter drainage alone. Surgical repair (D) is necessary only for intraperitoneal bladder ruptures. Without operative intervention of an intraperitoneal bladder rupture, lower urinary tract contamination will infect initially sterile urine and promote the development of subsequent bacterial peritonitis. Bladder repairs are never emergencies and should be performed following operative intervention for more severe, life-threatening injuries.

Further Reading:

#FOAMED

- http://www.emdocs.net/genitourinary-trauma-presentations-evaluation-and-management-updates/

- https://litfl.com/trauma-genitourinary-injuries/

- https://radiopaedia.org/articles/urinary-bladder-rupture?lang=us

References

- Gomez RG, Ceballos L, Coburn M, et al. Consensus statement on bladder injuries. BJU Int 2004; 94:27.

- Bjurlin MA, Fantus RJ, Mellett MM, Goble SM. Genitourinary injuries in pelvic fracture morbidity and mortality using the National Trauma Data Bank. J Trauma 2009; 67:1033.

- Terrier JE, Paparel P, Gadegbeku B, et al. Genitourinary injuries after traffic accidents: Analysis of a registry of 162,690 victims. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2017; 82:1087.

- Teeluckdharry B, Gilmour D, Flowerdew G. Urinary Tract Injury at Benign Gynecologic Surgery and the Role of Cystoscopy: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol 2015; 126:1161.

- Körner, M., Krötz, M. M., Degenhart, C., Pfeifer, K.-J., Reiser, M. F., & Linsenmaier, U. (2008). Current role of emergency us in patients with major trauma. RadioGraphics, 28(1), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1148/rg.281075047

- Richards JR, McGahan JP. Focused assessment with sonography in trauma (FAST) in 2017: What Radiologists Can Learn. Radiology 2017;283:30–48.doi:10.1148/radiol.2017160107

- Lumen N, Kuehhas FE, Djakovic N, et al. Review of the current management of lower urinary tract injuries by the EAU Trauma Guidelines Panel. Eur Urol 2015; 67:925.

- Brown D, Magill HL, Black TL. Delayed presentation of traumatic intraperitoneal bladder rupture. Pediatr Radiol 1986; 16:252.

- Quagliano PV, Delair SM, Malhotra AK. Diagnosis of blunt bladder injury: A prospective comparative study of computed tomography cystography and conventional retrograde cystography. J Trauma 2006; 61:410.

- Morgan DE, Nallamala LK, Kenney PJ, et al. CT cystography: radiographic and clinical predictors of bladder rupture. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2000; 174:89.

- Case courtesy of Dr Matt A. Morgan, <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/?lang=us”>Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/cases/41780?lang=us”>rID: 41780</a>

- Case courtesy of Dr Vikas Shah, <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/?lang=us”>Radiopaedia.org</a>. From the case <a href=”https://radiopaedia.org/cases/61059?lang=us”>rID: 61059</a>

- Morey AF, Brandes S, Dugi DD 3rd, et al. Urotrauma: AUA guideline. J Urol 2014; 192:327.

- Kotkin L, Koch MO. Morbidity associated with nonoperative management of extraperitoneal bladder injuries. J Trauma 1995; 38:895.