Author: Ramya Kondaveeti, MD (EM Resident Physician, ACMC/Oak Lawn, IL); Thaer Ahmad, MD (EM Attending Physician, Oak Lawn, IL) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Resident Physician, Zucker-Northwell NS/LIJ, NY); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 53-year-old female with a past medical history significant for hypertension presents to the ED with headache and dizziness. Her symptoms have been constant over the last two weeks. She was diagnosed with peripheral vertigo by her primary care doctor and sent home with meclizine which has not provided her with symptom relief.

Triage vital signs (VS) include BP 163/89, HR 78, T 98.4, RR 14, SpO2 98% on room air. On exam, no nystagmus is noted. Her extraocular movements and cranial nerves II-XII are intact, strength of all four extremities is 5/5 without any focal weakness, and there are no appreciable sensory deficits. There is, however, dysmetria of the right upper extremity.

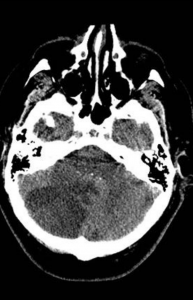

CT head without contrast1 reveals the following:

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Cerebellar Stroke

Epidemiology:

- 1-4% of cerebrovascular accidents occur in the cerebellum.2

- In the United States, approximately 795,000 people suffer from strokes every year.3

- Cerebellar strokes are associated with high morbidity and mortality. Infarction-associated edema can cause herniation, increased brainstem pressure, or obstruction of the 4th ventricle leading to obstructive hydrocephalus.3

- In comparison to cerebral strokes, the mortality rate associated with cerebellar strokes is nearly doubled.3

- While strokes in pediatric patients are more rare, posterior circulation strokes make up 30-40% of all childhood strokes.4

- Literature suggests that the average patient age is 62 years, with the most common underlying causes being atherosclerotic or cardioembolic disease. Less commonly, vertebral artery dissections will lead to cerebellar strokes which can be seen in younger patients.5

Pathophysiology:

- The cerebellum is supplied by three major arteries: the superior cerebellar artery, the anterior inferior cerebellar artery, and the posterior inferior cerebellar artery.

- Different types of cerebellar strokes can be defined by their vascular supply, though physical manifestations can frequently overlap or be atypical.2

- Superior cerebellar artery strokes most often present with headache, gait ataxia, dysarthria. Dizziness and vomiting are less commonly seen.8

- Posterior inferior cerebellar artery strokes present with severe dysphagia, dysarthria, dysphonia also known as lateral medullary syndrome.8

- Anterior inferior cerebellar artery strokes, also known as lateral pontine syndrome, present with the most widespread symptoms. This includes severe vertigo, nausea, vomiting, nystagmus, ipsilateral hemiataxia, ipsilateral Horner syndrome, facial weakness, loss of lacrimation, loss of salivation, loss of taste from anterior 2/3 of the tongue, loss of corneal reflex, loss of pain and temperature of the ipsilateral face and contralateral body.8

Evaluation:

- Distinguishing the difference between peripheral and central vertigo can be difficult. The most important distinction is peripheral vertigo is often accompanied by vestibulocochlear symptoms, can be triggered with positions, is intermittent, is usually without a headache, and does not demonstrate other neurologic deficits (vision, speech, gait abnormalities).10

- Physical examination should consist of a thorough neurological examination including assessment of the cranial nerves, motor function, sensation, speech, nystagmus, finger-to-nose, heel-to-shin, and gait evaluation.

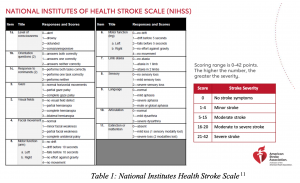

- The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale may also be beneficial in determining severity of strokes, though it is most useful for strokes affecting the anterior circulation stroke.

- Initial testing should include CT head without contrast to assess for a hemorrhagic stroke with addition of CTA head and neck if there is any concern for posterior circulation stroke.

- Definitive diagnosis of cerebellar infarction is made with MRI of the brain, as CT imaging (both non-contrast and IV contrast) is often unremarkable and has poor sensitivity for cerebellar stroke.

- ECG and laboratory analysis (glucose, CBC, electrolytes, renal/liver function, troponin, PT/PTT) also recommended.

Treatment:

- Treatment of cerebellar strokes depends on whether the etiology of the stroke is ischemic or hemorrhagic.

- Patients with intracranial hemorrhage should have a formal neurosurgical evaluation to determine supportive or surgical management.

- Anticoagulation reversal as needed:

- Provide prophylactic anti-epileptic treatment with levetiracetam 20mg/kg IV.

- Management of blood pressure is key for treatment and can be managed with labetalol pushes and/or an infusion of nicardipine or clevidipine4

- Prior to acute reperfusion in ischemic stroke, goal blood pressure is < 185/110

- 24 hours after acute reperfusion in ischemic stroke, goal blood pressure <180/105

- Hemorrhage stroke goal is dependent upon initial blood pressure

- Initial systolic blood pressure 150-220, goal systolic blood pressure 140

- Initial systolic blood pressure > 220, goal systolic blood pressure 140-160

- Give a 100mL bolus of 3% hypertonic saline or mannitol for signs and symptoms of cerebral edema.12

- Keep the head of the bed elevated to 30 degrees and if the patient is intubated, set the respiratory rate higher to temporarily treat cerebral edema until definitive management.

- Cerebellar infarctions can be candidates for thrombolysis if within the correct time frame of 4.5 hours and the deficit is substantial enough to warrant its use as there is a high risk of bleeding.

- If no thrombolysis, they should get aspirin 324 mg

- If they receive thrombolysis, aspirin should be held for 24 hours

- Endovascular therapy including mechanical thrombectomy and aspiration is reserved for severe posterior circulation strokes as the benefit has historically not been better than medical management.9

Disposition:

- Patients with diagnosed cerebellar stroke or highly suspected cerebellar stroke should be admitted for further evaluation and management.

- Admit to a telemetry floor or neurological intensive care unit dependent on clinical presentation and management. Patients receiving thrombolysis will require ICU admission for neurologic monitoring.

Pearls:

- Cerebellar strokes can present as dizziness, nausea and vomiting, ataxia, and/or dysarthria.

- Edema from infarction in the posterior fossa can result in severe brainstem injury, herniation, and death.

- Treat hemorrhagic cerebellar strokes medically with anticoagulant reversal therapy as indicated, prophylactic anti-epileptic treatment, blood pressure management, and hypertonic saline or mannitol for cerebellar edema.

- Ischemic cerebellar strokes should be treated with aspirin and can be considered for thrombolytic therapy if within the correct timeframe.

A 37-year-old woman presents with a sudden onset of vertiginous symptoms. Which of the following physical exam findings would be concerning for a central cause of her vertigo?

A) Corrective saccade when quickly rotating the patient’s head laterally leftward

B) Deviation of the right eye after covering it, followed by a correction when uncovered

C) Right-beating nystagmus on lateral gaze

D) Vertigo onset when turning the patient’s head laterally and laying them supine

Answer: B

Skew deviation of the eyes with sequential covering would be concerning for a central process as the source of this patient’s vertigo. Dizziness is a common presenting concern for patients, and further questioning should distinguish vertigo (room spinning) and presyncope (lightheadedness). The vestibular system relies on visual cues, the inner ear, and the cerebellum to maintain equilibrium. Posterior circulation strokes can cause vertigo and should be distinguished from benign causes of peripheral vertigo. The head impulse, nystagmus, test of skew (HINTS) exam can help distinguish peripheral from central causes of vertigo and can be more sensitive than MRI when used by trained physicians. It should only be performed on patients with ongoing vertiginous symptoms. Skew deviation should be assessed with the sequential covering of the eyes while the patient looks at a fixed point. Deviation of either eye with covering and uncovering is concerning for a central process.

Nystagmus (C) should be evaluated with patients looking both forward and laterally. Vertical, rotary, or bidirectional nystagmus is concerning for a central process. Head impulse (A) should be evaluated by having the patient look at a fixed point while the physician quickly rotates their head 20° laterally. Patients with vestibular neuritis will have a unilateral corrective saccade away from the affected side. The Dix-Hallpike maneuver (D)often recreates vertiginous symptoms in patients with benign paroxysmal peripheral vertigo.

Further Reading

- http://www.emdocs.net/posterior-circulation-strokes-why-do-we-miss-them-and-how-do-we-improve/

- http://www.emdocs.net/posterior-circulation-strokes-dizziness-pearls-pitfalls/

- https://emergencymedicinecases.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Himmel-Vertigo-Summary-2017.pdf

- https://foamcast.org/2016/01/12/episode-41-vertigo/

- https://coreem.net/core/posterior-circulation-stroke/

References:

- Stanislavsky A, Baba Y, Hacking C, et al. Cerebellar infarction. Reference article, Radiopaedia.org (Accessed on 03 Jan 2023) https://doi.org/10.53347/rID-19246

- Ioannides K, Tadi P, Naqvi IA. Cerebellar Infarct. [Updated 2022 May 8]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470416/

- Ma JO, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Stapczynski SJ, Cline DM, Thomas SH. Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide. 9th ed. (Tintinalli JE, ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill; 2019.

- Sarikaya H, Steinlin M. Cerebellar Stroke in Adults and Children. Handb Clin Neurol. 2018;155:301-312. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-64189-2.00020-2. PMID: 29891068.

- Barinagarrementeria F, Amaya LE, Cantu C. Causes and Mechanisms of Cerebellar Infarction in Young Patients. Stroke. 1997; 28 (12): 2400–2404.

- Brief Review in Cerebellar Stroke. Siriraj Stroke Center. Updated March 14, 2018. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://www.sirirajstrokecenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/cerebellar-stroke_edit.pdf

- Terao S, Sobue G, Izumi M, Miura N, Takeda A, Mitsuma T. Infarction of Superior Cerebellar Artery Presenting as Cerebellar Symptoms. Stroke. 1996; 27 (9) 1679—1681.

- Fogwe DT, Sandhu DS, Goyal A, et al. Neuroanatomy, Anterior Inferior Cerebellar Arteries. [Updated 2022 Jul 25]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK448167/

- Raymond S, Rost NS, Schaefer PW, Leslie-Mazwi T, Hirsch JA, Gonzalez RG, Rabinov J. Patient selection for mechanical thrombectomy in posterior circulation emergent large-vessel occlusion. Interv Neuroradiol. 2018 Jun;24(3):309-316. doi: 10.1177/1591019917747253. Epub 2017 Dec 12. PMID: 29231792; PMCID: PMC5967176.

- Lui F, Foris LA, Willner K, et al. Central Vertigo. [Updated 2022 Jul 4]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK441861/

- Fussner J, Velasco C. Stroke Coordinator Boot Camp Assessing Stroke— Scores & Scales. American Heart Association. Accessed January 17, 2023. https://www.heart.org/-/media/files/affiliates/gra/gra-qsi/2019-scbc-presentations/5–assessing-stroke–scores–scales-v2.pdf?la=en

- Schwarz S, Schwab S, Bertram M, Aschoff A, Hacke W. Effects of Hypertonic Saline Hydroxyethyl Starch Solution and Mannitol in Patients with Increased Intracranial Pressure After Stroke. Stroke. 1998; 29(8):1550-1555. 10.1161/01.str.29.8.1550