Authors: Rahul Ramraj, MD (EM Resident Physician, Zucker SOM at Northwell NS/LIJ); Pinaki Mukherji, MD (EM/IM Associate Professor, Zucker SOM at Hofstra/Northwell)// Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Resident Physician, Zucker-Northwell NS/LIJ, NY), Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 60-year-old female with diabetes and hypertension from skilled nursing facility presents with worsening mental status, shortness of breath, and muscle weakness. Vital signs include BP 175/100, HR 105, RR 22, SpO2 95% on room air, T 100.7F, and blood glucose of 275. Physical exam is remarkable for A&Ox2, obesity, striae, bilateral upper/lower extremity muscle weakness, and 2+ bilateral lower extremity edema. CMP/CBC is unremarkable, BNP is 250, and EKG shows low voltage. Outpatient random serum cortisol is 2700 nmol/L.

What is the diagnosis, and urgent interventions will reduce the patient’s morbidity/mortality?

Answer: Cushing’s syndrome

Lower elevated serum cortisol with metyrapone, ketoconazole, or etomidate for the underlying severe Cushing’s syndrome.

Introduction

- Cushing’s syndrome (CS): prolonged exposure to excess cortisol state [1,2]

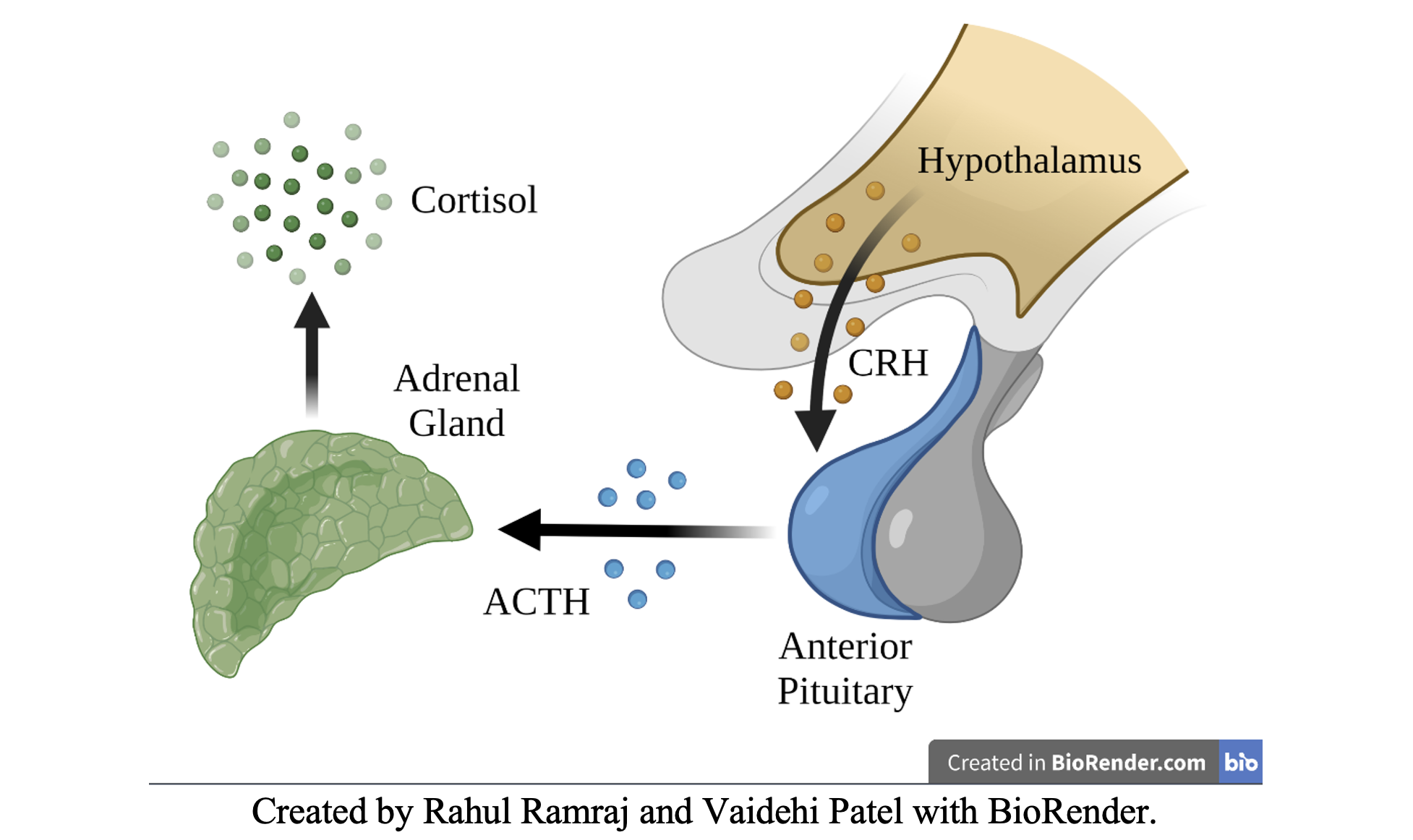

- Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal (HPA) Axis

- Hypothalamus – secretes Cortisol Releasing Hormone (CRH)

- Pituitary – secretes Adrenocorticotropin Hormone (ACTH)

- Adrenal Glands – secretes Cortisol

- Primary causes of excess mortality rate in CS [3]

- Cardiovascular disease (CHF/ischemia)

- Venous thrombosis

- Infection

Classifications/Epidemiology

- Exogenous (Iatrogenic) CS – most common etiology of CS [2]

- Endogenous CS – 0.7-2.4 per million population per year [2]

- ACTH-dependent – 80-85% of endogenous CS cases

- Pituitary Adenoma (Cushing’s disease) – 75-80% of ACTH-dependent CS cases

- Ectopic ACTH – 15-20% of ACTH-dependent CS cases

- Most severe CS and highest mortality rate [3,4]

- CRH-producing Tumor – <1% of ACTH-dependent CS cases

- ACTH-independent – 15-20% of endogenous CS cases

- Unilateral Adrenal Tumor – 90% of ACTH-independent CS cases

- Median Age of Diagnosis – 41.4 years [4]

- Female-to-Male ratio of 3:1 [4]

- ACTH-dependent – 80-85% of endogenous CS cases

Clinical Presentation

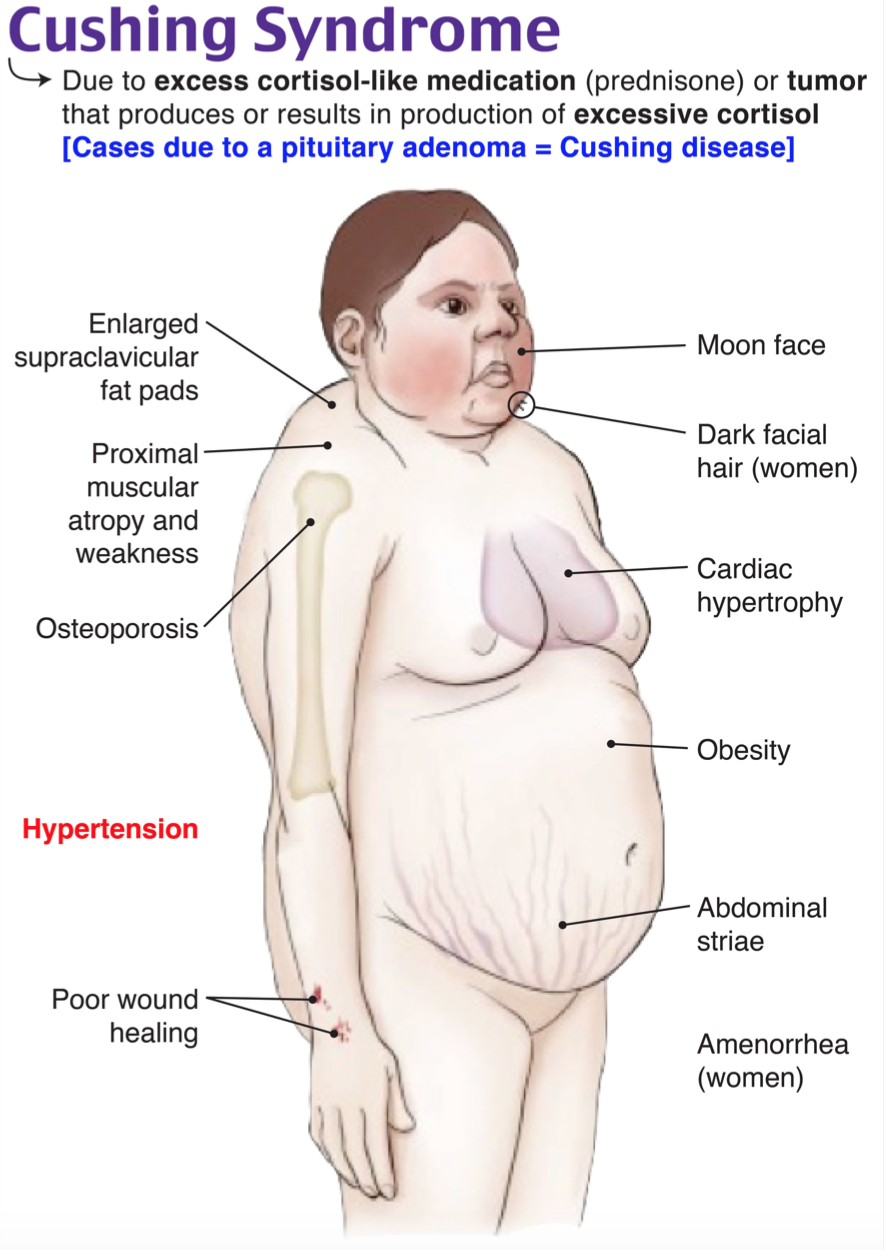

- Sensitive and common symptoms (>70% prevalence) [2]

- General: obesity or weight gain, rounded faces (moon facies)

- Skin: hirsutism/alopecia, facial plethora

- Gonads: menstrual irregularity

- MSK: muscle weakness/atrophy, decreased linear growth in children

- Metabolic: hypertension, hyperlipidemia

- Specific but less common symptoms (<70% prevalence) [2]

- Supraclavicular/dorsocervical fat pads (50% prevalence)

- Violaceous striae (44-50% prevalence)

- Neuropsychiatric: emotional lability/depression, psychosis/mania, cognitive dysfunction/short-term memory loss (<30% prevalence)

Evaluation

- Detailed medical and drug history [1]

- Differential diagnosis of hypercortisolism [2]

- Pregnancy

- Glucocorticoid resistance

- Pseudo-Cushing’s states (increased CRH secretion) – alcoholism, depression, severe obesity, anorexia nervosa, bulimia

- Diagnostic Tests – (typically inpatient/outpatient setting) [2]

- 24-hour urinary free cortisol (UFC): >3 x upper limit of normal

- Late-night salivary cortisol: >145 ng/dL

- Midnight serum cortisol: >7.5 µg/dL (awake) or >1.8 µg/dL (sleeping)

- Low-dose dexamethasone suppression test (DST)

- Severe CS (any of the following) requires urgent treatment [1,3]

- High random serum cortisol >36 µg/dL (1000 nmol/L) *ED serum test

- 24-hour UFC >4 x upper limit of normal

- Established CS with any of the following complications: sepsis, intractable hypokalemia (<3.0 mmol/L), uncontrolled hypertension, heart failure, GI hemorrhage/perforation, acute psychosis, thromboembolism, or uncontrolled hyperglycemia and ketoacidosis

Treatment

- Approach to non-emergent CS:

- First-line Treatments: resection of primary lesion(s) or taper exogenous steroid [3]

- Second-line Treatments: medication therapy, radiation therapy [3]

- Approach to severe CS

- Initiate medical treatment prior to completion of CS diagnostic tests [3]

- Medical Intervention

- Treatment rapidly improves life-threatening complications

- Steroidogenesis inhibitors – reduces serum cortisol in 24-48 hrs [3]

- Metyrapone monotherapy [1,3]

- 250 mg PO q6h, max 6 g/day divided into 3-4 doses/day

- Ketoconazole monotherapy [1,3]

- 200 mg PO q12h, max 1.2-1.6 g/day divided into 3-4 doses/day

- Etomidate – severely ill patients or if unable to tolerate PO [1,3,5]

- Loading dose 3-5 mg IV, continuous IV infusion of 0.03-0.10 mg/kg/h

- ICU – titrate to serum cortisol level of 150-300 nmol/L

- Metyrapone monotherapy [1,3]

- Glucocorticoid receptor antagonist – consider for hyperglycemia [1,3]

- Mifepristone

- 300 mg PO q24h, max 1200 mg/day PO

- Mifepristone

- Steroidogenesis inhibitors – reduces serum cortisol in 24-48 hrs [3]

- Treat Comorbidities/Complications:

- High Blood Pressure – resolution of hypercortisolism improves blood pressure control in up to 30-70% of patients [4]

- Metyrapone monotherapy and ketoconazole monotherapy lead to the greatest improvement in blood pressure

- Heart failure (fluid retention + hypertension), hypokalemia [1]

- Spironolactone 50-100 mg/day PO [1]

- Alternatives: triamterene or amiloride [1]

- Anticoagulation: low molecular weight heparin [1,6]

- Factors influencing start of thromboprophylaxis – hypercortisolism severity, previous VTE, limitation of mobility

- Sepsis or Opportunistic Infections [1]

- Pneumocystis pneumonia prophylaxis – trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole or dapsone

- Diabetes Mellitus (DM) control

- Mifepristone – approved for CS and hyperglycemia [4]

- Insulin administration after reducing serum cortisol [1]

- Mental status changes (i.e. acute psychosis) – haloperidol [1]

- High Blood Pressure – resolution of hypercortisolism improves blood pressure control in up to 30-70% of patients [4]

- Treatment rapidly improves life-threatening complications

- Surgical Intervention – after medical intervention in critically ill patients

- Bilateral adrenalectomy – rapid resolution of refractory hypercortisolemia, preferably with preoperative cortisol-lowering medication [1]

- Disposition – ICU management

- Close follow up of serum or urine free cortisol to stabilize HPA axis

- Monitor for adrenal insufficiency requiring glucocorticoid replacement

Pearls

- Consider CS when one sensitive and one specific sign (i.e.: obesity + striae; hirsutism + new psychosis)

- Begin empiric treatment if severe CS suspected: metyrapone, ketoconazole, or etomidate

- Confirm suspicion with random serum cortisol > 36 µg/dL (1000 nmol/L)

- Treat associated disorders – cardiovascular disease (cardiac failure, hypertension), venous thrombosis, infections (sepsis, peritonitis), metabolic complications (diabetes, hypokalemia)

- Bilateral adrenalectomy – when refractory to medical interventions in severe CS

A 32-year-old woman with a history of asthma, systemic lupus erythematosus, and chronic prednisone use presents to the emergency department with concerns for several wounds over her upper extremities that have not healed for weeks, despite local wound care. She cannot recall any recent trauma or falls. Her BP is 150/93 mm Hg. Physical examination reveals a dorsocervical fat pad and scattered ecchymoses and abrasions in varying stages of healing over the bilateral upper and lower extremities. Her skin appears diffusely atrophic, and her mucous membranes appear pink and moist. What is the most likely etiology of her physical examination findings?

A) Adrenal adenoma

B) Chronic corticosteroid use

C) Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone secretion

D) Pituitary adenoma

Answer: B

This patient is presenting with delayed wound healing secondary to underlying iatrogenic Cushing syndrome in the setting of chronic glucocorticoid use. Other etiologies of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-independent Cushing syndrome include adrenal adenoma and adrenal hyperplasia. ACTH-dependent causes of Cushing syndrome (often termed Cushing disease in this scenario) include ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor, ectopic ACTH secretion, and ectopic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion. Signs and symptoms include dysmenorrhea and hirsutism in women, skin striae, delayed wound healing, glucose intolerance, obesity, and fat deposition in characteristic regions (dorsocervical fat pad, moon facies), hypertension, proximal muscle wasting and weakness, osteoporosis or fractures, and neuropsychiatricside effects. These patients have an increased risk of thromboembolism events and cardiovascular disease. Diagnosis is typically made in the outpatient setting by 24-hour free cortisol or dexamethasone suppression testing. Management includes treatment of the underlying cause, such as tapering and discontinuing glucocorticoids as in this patient.

This patient is presenting with delayed wound healing secondary to underlying iatrogenic Cushing syndrome in the setting of chronic glucocorticoid use. Other etiologies of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH)-independent Cushing syndrome include adrenal adenoma and adrenal hyperplasia. ACTH-dependent causes of Cushing syndrome (often termed Cushing disease in this scenario) include ACTH-secreting pituitary tumor, ectopic ACTH secretion, and ectopic corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) secretion. Signs and symptoms include dysmenorrhea and hirsutism in women, skin striae, delayed wound healing, glucose intolerance, obesity, and fat deposition in characteristic regions (dorsocervical fat pad, moon facies), hypertension, proximal muscle wasting and weakness, osteoporosis or fractures, and neuropsychiatricside effects. These patients have an increased risk of thromboembolism events and cardiovascular disease. Diagnosis is typically made in the outpatient setting by 24-hour free cortisol or dexamethasone suppression testing. Management includes treatment of the underlying cause, such as tapering and discontinuing glucocorticoids as in this patient.

Further Reading

- Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline for CS: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4525003/

- Wiki EM: https://www.wikem.org/wiki/Cushing%27s_syndrome

- Emergency Central: https://emergency.unboundmedicine.com/emergency/view/5-Minute_Emergency_Consult/307292/all/Cushing_Syndrome

References

- Alexandraki KI, Grossman AB. Therapeutic Strategies for the Treatment of Severe Cushing’s Syndrome. Drugs. 2016;76(4):447-458. doi:10.1007/s40265-016-0539-6

- Sharma ST, Nieman LK, Feelders RA. Cushing’s syndrome: epidemiology and developments in disease management. Clin Epidemiol. 2015;7:281-293. Published 2015 Apr 17. doi:10.2147/CLEP.S44336

- Nieman LK, Biller BM, Findling JW, et al. Treatment of Cushing’s Syndrome: An Endocrine Society Clinical Practice Guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2015;100(8):2807-2831. doi:10.1210/jc.2015-1818

- Li D, El Kawkgi OM, Henriquez AF, Bancos I. Cardiovascular risk and mortality in patients with active and treated hypercortisolism. Gland Surg. 2020;9(1):43-58. doi:10.21037/gs.2019.11.03

- Lutgers HL, Vergragt J, Dong PV, et al. Severe hypercortisolism: a medical emergency requiring urgent intervention. Crit Care Med. 2010;38(7):1598-1601. doi:10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181e47b7a

- Van Haalen FM, Kaya M, Pelsma ICM, et al. Current clinical practice for thromboprophylaxis management in patients with Cushing’s syndrome across reference centers of the European Reference Network on Rare Endocrine Conditions (Endo-ERN). Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2022;17(1):178. Published 2022 May 3. doi:10.1186/s13023-022-02320-x