Authors: Haley Sinatro, MD (EM Resident Physician, UTSW EM); Alan John, MD (Assistant Professor, UTSW EM) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, Northwell, NY); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 37-year-old G2P2 female with no other past medical history presents to the ED with a 2-day history of intermittent fever and foul-smelling vaginal discharge. She was discharged 3 days prior after a cesarean delivery to a single, full term, live born infant complicated by premature rupture of membranes. She notes associated chills and abdominal tenderness. On exam, she is ill appearing, tachycardic, and febrile. Her surgical incision is clean, dry, and intact. She has significant tenderness to the lower abdomen on palpation. On pelvic exam, she has moderate thick, foul-smelling purulent discharge.

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Endometritis

Epidemiology

- Endometritis in the ED is more likely to be an acute presentation; chronic endometritis is a less common presentation

- Most acute endometritis cases occur after a cesarean section (C-section) 1-6 weeks postpartum

- Endometritis is 10-30x more common after C-section vs vaginal birth

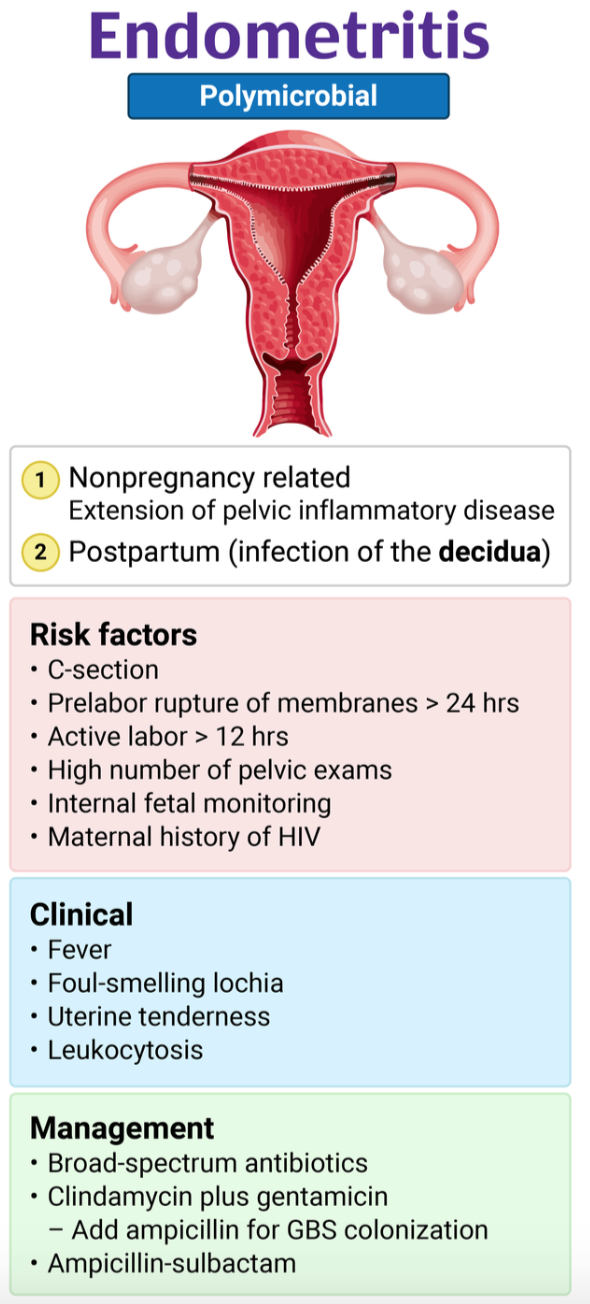

- Endometritis unrelated to pregnancy is less common, but can be precipitated by pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), sexually transmitted infections (STI) or a gynecologic procedure

- Other risk factors include: chorioamnionitis, prolonged labor, prolonged rupture of membranes, multiple cervical exams, internal fetal monitoring, large meconium in amniotic fluid among others1

- Microbiology:

- Postpartum infections are typically polymicrobial and involve 2-3 aerobes/anaerobes from the lower genital tract2

- Non-pregnancy related infections:

- Commonly due to progressive pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), a polymicrobial infection

- Strong association exists with chlamydial colonization/infection of the cervix3

- For TB endemic countries, upper genital tuberculous infections are common4

- Commonly due to progressive pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), a polymicrobial infection

Pathophysiology

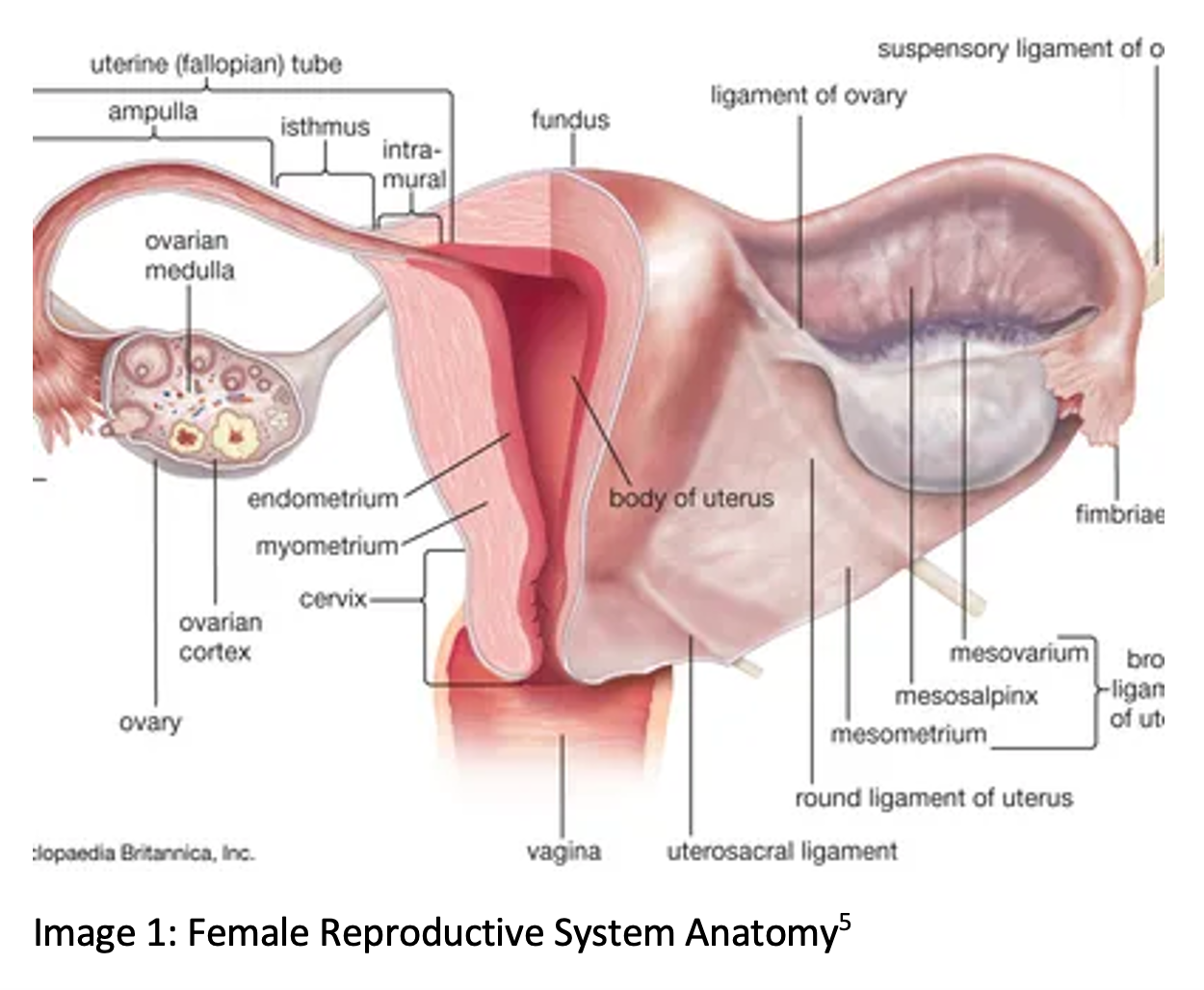

- Endometritis refers to inflammation of the endometrium; in postpartum endometritis it refers to infection of the decidua (pregnancy endometrium) and can extend to all uterine layers

- In non-pregnancy related endometritis, infections commonly occur in an ascending fashion (PID progressing to endometritis/salpingitis)

Clinical Presentation

- In postpartum and in non-pregnancy related infections, patients may present with fever, uterine tenderness, tachycardia, lower abdominal pain

- May also see malodorous discharge and vaginal bleeding on genitourinary exam

- Timing of symptoms is dependent on antepartum vs intrapartum vs postpartum development of infection as well as microbiology

- Attention should be paid to signs of severe/systemic infection or signs of sepsis, including fever, hypotension, tachycardia, tachypnea, and leukocytosis

- Severe infections can spread to peritoneal cavity and cause peritonitis, intraabdominal abscesses, or sepsis

- Even rarer complicated cases may involve necrotizing myometritis, necrotizing fasciitis of the abdominal wall, and septic pelvic thrombophlebitis

Evaluation

- Diagnosis is frequently made on clinical context and presentation

- Lab findings are nonspecific, but may include:

- WBC 15,000 – 30,000; keeping in mind that elevations can be normal with physiologic leukocytosis of pregnancy6

- Bacteremia: 5-20% of patients7

- Imaging: there are no characteristic imaging findings on either US or CT to guide diagnosis; many findings overlap with normal postpartum uterus

- Possible ultrasound findings:

- Thickened and heterogenous endometrium

- Intracavitary/cul-de-sac fluid

- Increased vascularity with use of Doppler

- Intrauterine air

- Utility of imaging:

- Eliminating other etiologies from differential: appendicitis, surgical site abscess/infection, torsion, pyelonephritis, etc.

- Evaluate for retained products of conception as etiology

- Possible ultrasound findings:

Diagnosis

- Diagnosis of endometritis with at least two of the following:8

- Fever >100.4F

- Abdominal or uterine tenderness without other cause

- Purulent uterine drainage

Treatment5

- Initial treatment

- Address ABCs

- Fluid resuscitation as indicated by clinical picture

- Antibiotics (table 1)

- Consult OB/GYN

Disposition

- Admit all patients who appear ill, present after C-section, or have significant comorbidities

- Consult OB/GYN for all patients who appear post C-section, or appear ill

Pearls

- Endometritis is largely a clinical diagnosis

- Endometritis outside pregnancy is possible and should remain on differential for suspected gynecologic cause of lower abdominal pain

- Low threshold for admission due to possibility of resistant infections, possibility of intra-abdominal extension of infections

A 25-year-old woman presents with abdominal pain. She was discharged 3 days ago after undergoing an uncomplicated cesarean section. On the day of discharge, she only had some minor discomfort, but she states that, over the past day and a half, the pain has significantly worsened. Vital signs are remarkable for T 39°C, HR 120 bpm, BP 95/50 mm Hg, RR 28/min, and SpO2 99%. Physical exam is remarkable for severe pelvic discomfort with palpation in the right lower or left lower quadrants of the abdomen. Her incision is intact without drainage or erythema. Pelvic exam reveals a foul-smelling vaginal discharge and uterine tenderness. Which of the following is the best next step in management?

A) Administer ceftriaxone 500 mg IM and doxycycline 100 mg PO

B) Consult OB/GYN for incision and drainage

C) Establish IV access and administer clindamycin and gentamicin

D) Prescribe doxycycline with metronidazole and ensure close OB/GYN follow-up

Answer: C

Most postpartum infections are identified after hospital discharge. In a postpartum woman with a fever, pelvic infection is presumed until proven otherwise. Risk factors for postpartum endometritis include multiple gestations, cesarean section, younger maternal age, long duration of labor and membrane rupture, internal fetal monitoring, and low socioeconomic level. Clinical features include fever, foul-smelling lochia, leukocytosis, tachycardia, pelvic pain, and uterine tenderness. The diagnosis is clinical, and close consultation with the patient’s OB/GYN may be helpful in determining disposition. Admission is needed for those who appear ill, have had a cesarean section, or have underlying comorbidities. Treatment consists of antibiotics and, on some occasions, debridement of necrotic tissue or abscess drainage. The preferred inpatient empiric antibiotics are clindamycin and gentamicin, as this remains the most effective regimen to treat postpartum endometritis.

Administering ceftriaxone 500 mg IM and doxycycline 100 mg PO (A) would be the appropriate treatment option for those with simple cervicitis. However, this patient has a history more concerning for postpartum endometritis. Also, the patient appears ill and septic. Therefore, these antibiotics would not be appropriate in the event that the patient had pelvic inflammatory disease or endometritis secondary to chlamydia or gonorrhea.

Consulting OB/GYN for incision and drainage (B) would be the appropriate treatment for an abscess.

Prescribing doxycycline with metronidazole and ensuring close OB/GYN follow-up (D) would be a treatment option for patients with mild postpartum endometritis. This patient appears septic and recently underwent a cesarean section delivery, which makes hospital admission and parenteral antibiotics the better choice for management. In addition, doxycycline should be avoided in breastfeeding patients.

Further Reading:

FOAM

- https://wikem.org/wiki/Postpartum_endometritis

- https://www.emdocs.net/postpartum-endometritis-ed-setting-presentation-evaluation-management/

References

- Chaim W, Bashiri A, Bar-David J, Shoham-Vardi I, Mazor M. Prevalence and clinical significance of postpartum endometritis and wound infection. Infect Dis Obstet Gynecol. 2000;8(2):77-82. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-0997(2000)8:2<77::AID-IDOG3>3.0.CO;2-6. PMID: 10805361; PMCID: PMC1784665.

- Casey BM, Cox SM. Chorioamnionitis and endometritis. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 1997 Mar;11(1):203-22. doi: 10.1016/s0891-5520(05)70349-4. PMID: 9067792.

- Paukku M, Puolakkainen M, Paavonen T, Paavonen J. Plasma cell endometritis is associated with Chlamydia trachomatis infection. Am J Clin Pathol. 1999 Aug;112(2):211-5. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/112.2.211. PMID: 10439801.

- Jindal UN, Verma S, Bala Y. Favorable infertility outcomes following anti-tubercular treatment prescribed on the sole basis of a positive polymerase chain reaction test for endometrial tuberculosis. Hum Reprod. 2012 May;27(5):1368-74. doi: 10.1093/humrep/des076. Epub 2012 Mar 14. PMID: 22419745.

- Morens, David. “Endometritis”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 6 Feb. 2024, https://www.britannica.com/science/endometritis. Accessed 7 February 2024.

- Acker DB, Johnson MP, Sachs BP, Friedman EA. The leukocyte count in labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1985 Dec 1;153(7):737-9. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90335-7. PMID: 4073137.

- Kankuri E, Kurki T, Carlson P, Hiilesmaa V. Incidence, treatment and outcome of peripartum sepsis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 2003 Aug;82(8):730-5. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0412.2003.00265.x. PMID: 12848644.

- Moldenhauer, Julie S. “Postpartum Endometritis – Gynecology and Obstetrics.” Merck Manuals Professional Edition, Merck Manuals, 29 Jan. 2024, https://www.merckmanuals.com/professional/gynecology-and-obstetrics/postpartum-care-and-associated-disorders/postpartum-endometritis

- Mackeen AD, Packard RE, Ota E, Speer L. Antibiotic regimens for postpartum endometritis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2015 Feb 2;2015(2):CD001067. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001067.pub3. PMID: 25922861; PMCID: PMC7050613.