Author: Beau Curet, MD (EM Resident Physician, UTSW / Parkland Memorial Hospital) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 23-year-old female presents with acute onset lower abdominal pain for the past 3 days that started shortly after she started her period. She says she has also had abnormal vaginal discharge. She denies fevers, chills, nausea, vomiting, dysuria, hematuria, diarrhea, and constipation. She is sexually active with one partner of 3 months and inconsistently uses condoms.

Vitals signs in triage are BP 128/73, HR 79, T 97.9 Oral, RR 16, SpO2 100% on RA. She is well-appearing and non-toxic. Abdominal exam shows mild bilateral lower abdominal tenderness without guarding, and speculum exam shows small amount of blood (patient is on her menses), as well as cervical discharge. Bimanual exam is significant for bilateral adnexal tenderness and cervical motion tenderness. Urine pregnancy test is negative.

What is the patient’s diagnosis? What’s the next step in your evaluation and treatment?

Answer: Pelvic Inflammatory Disease

Background:

Infection in females ascending from the cervix and vagina, causing inflammation of the upper genital tract including uterus, fallopian tubes, and ovaries, and occasionally causing a tubo-ovarian abscess. Infection can also extend to the peritoneal cavity causing pelvic peritonitis, peri-appendicitis, and peri-hepatitis (Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome).1,2,3

- Most common serious infection in sexually active females 16-25.3

- PID is typically the result of progression of an initial sexually transmitted infection (STI) of the lower genital tract.3

- Although mortality from complications of PID is rare, treatment of PID is necessary to prevent long-term sequelae including infertility, chronic pelvic pain and scarring, tubo-ovarian abscess, and ectopic pregnancy.2,3,4

- Many cases of PID or initial STI are asymptomatic.2,4

- Because of the difficulty of diagnosis of PID and the potential for complications and infertility, providers should have low threshold to diagnose and empirically treat when PID is suspected.5

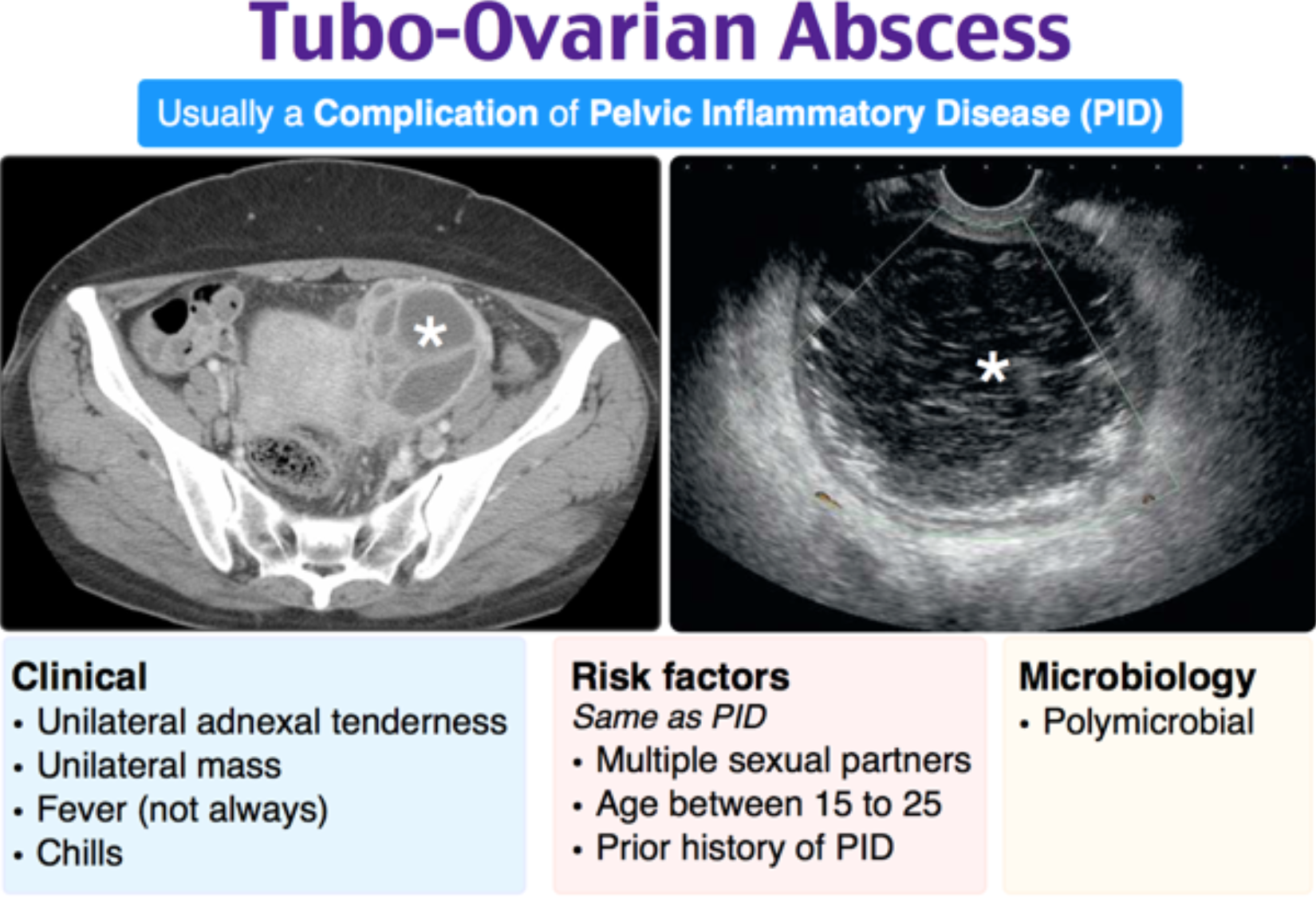

- Most common cause of death is ruptured tubo-ovarian abscess, which carries a 5-10% mortality rate.3

Risk factors:

- Risk factors include adolescence/young adulthood, younger onset of sexual activity, multiple sexual partners, no barrier protection during intercourse, history STI/PID, sexual abuse, recent IUD insertion, frequent douching, lower socioeconomic status, co-infection with other STIs/HIV, and recent abortion.1,3,6

- Additional risk factors for development of TOA include previous history of PID, delayed treatment, and HIV co-infection.1,3,6

Pathophysiology:

- PID is typically a result of ascending untreated STI from the cervix and vagina, with the most common microbial culprits being Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis. A less common sexually transmitted etiology is Mycoplasma genitalium.2

- PID is often polymicrobial, especially in advanced disease (presence of TOA).2,3

- Alternate, often non-sexually transmitted causes of PID include the same vaginal flora implicated in bacterial vaginosis, respiratory and enteric pathogens, and viruses.

Clinical presentation:

- Presentation is variable, and many patients are asymptomatic and may develop long-term sequelae due to delayed diagnosis and treatment.3,4

- Most common complaints are lower abdominal/pelvic pain and vaginal discharge.3

- Pain is classically described as acute onset during or directly after menses, bilateral lower abdominal in location, dull or crampy, and exacerbated by movement or intercourse.3,4

- Patients less commonly present with lower back pain, vaginal bleeding (postcoital bleeding, bleeding between menstrual cycles), pain with intercourse, or dysuria.2

- Systemic symptoms (nausea, vomiting, chills, fever) are usually absent, and if present, may indicate advanced disease.2

- RUQ pain can indicate presence of Fitz-Hugh-Curtis syndrome (peri-hepatitis).2

Differential diagnosis:

- Ectopic pregnancy, cervicitis, bacterial vaginosis, endometriosis, ovarian cyst, ovarian torsion, fibroids, menstrual cramps, mittelschmerz, spontaneous/septic abortion, cholecystitis, gastroenteritis, appendicitis, diverticulitis, UTI/pyelonephritis, nephrolithiasis.2,3

Evaluation and Diagnosis:

- Pelvic inflammatory disease is a clinical diagnosis based on the finding of pelvic organ tenderness in combination with signs/symptoms of lower genital tract inflammation.4

- No single complaint, physical exam finding, or laboratory finding is highly sensitive or specific for PID, so diagnosis involves consideration of all risk factors, physical exam findings, lab findings and overall clinical presentation.6

- History/physical exam:

- Pertinent past medical history includes previous STIs and STI treatment, HIV status, history of endometriosis, number of sexual partners, use of barrier protection, vaginal douching, and substance abuse.2,3

- Physical exam in the emergency department should include four components: vital signs, abdominal exam, bimanual pelvic exam, and vaginal speculum exam.2

- Physical exam may include lower abdominal tenderness, cervical motion tenderness, uterine or adnexal tenderness, and signs of lower genital tract inflammation.3

- Signs of lower genital tract inflammation include mucopurulent exudate from cervical os, presence of yellow or green mucus on cotton-tipped swab placed into cervical os (positive “swab test”), cervical friability (easily elicited bleeding on “swab test”), or many WBCs on wet mount of vaginal secretions.2,4

- TOA or pyosalpinx should be suspected in anyone with a palpable adnexal mass or disproportionate unilateral adnexal tenderness.2,3

- Vital sign abnormalities including fever and tachycardia are rare and may indicate presence of TOA, pyosalpinx, or peritonitis. Hypotension should prompt consideration of ruptured TOA, aggressive resuscitation, and surgical consultation.2

- Labs:

- Every female of childbearing age should receive pregnancy test in the ED.2,3

- N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis nucleic acid amplification test (NAAT) and vaginal wet mount should also be routinely sent in any patient in ED in which PID is suspected.

- Absence of abundant WBCs on wet mount has been shown to have a significant negative predictive value for PID.3

- If PID is suspected, send testing for possible concomitant STI infection (RPR for syphilis, HIV, and hepatitis).3

- An abnormal urinalysis does not predict or exclude PID. Any pelvic inflammation including PID can cause WBCs in the urine.2,3

- ESR, CRP, and WBC are nonspecific when elevated and have limited usefulness in diagnosis of PID. Elevation may support diagnosis of PID when already clinically suspected.2,3

- Imaging:

- Not routinely needed for diagnosis or management of PID in the emergency department.2

- Reasons for obtaining imaging in the emergency department include:

- Suspected TOA (palpable adnexal mass, vital sign abnormalities or disproportionate unilateral adnexal tenderness).3

- Exclusion of other causes of pelvic and lower abdominal pain.2,3

- First line imaging modality is transabdominal or transvaginal ultrasonography.2

- Ultrasound lacks sufficient sensitivity to rule out PID if normal; however, certain findings which are specific for PID if seen include thick tubal walls (>5 mm), fluid-filled fallopian tubes, hyperemia of pelvic structures on doppler, and cogwheel sign.2,3

- Pelvic or tubo-ovarian abscesses appear on US as complex adnexal masses with internal echoes. US can detect up to 70% of adnexal masses missed on physical exam. CT pelvis can be obtained as a second line modality to assess for suspected TOA that is not visualized on US.1,3

- CT abdomen/pelvis is the most useful imaging modality for assessing for appendicitis or other causes of acute abdominal/pelvic pain in the emergency department.2,3

- MRI is the most sensitive and specific imaging modality for PID, with sensitivity/specificity as high as 98% and 95%, respectively, though it is often not available.2

- Current CDC treatment/diagnostic guidelines5:

- Recommend empiric treatment for PID if one of three following minimum clinical criteria are met and no alternative cause of pain is found: cervical motion tenderness, uterine tenderness, or adnexal tenderness.

- One of more of following additional clinical criteria in combination with one of minimum criteria mentioned above increase the specificity for diagnosis of PID: oral temp >101 F, abnormal cervical mucopurulent discharge or cervical friability, abundant WBCs on wet mount, elevated ESR/CRP, and lab documentation of cervical N. gonorrhoeae or C. trachomatis infection.

Management:

- The goal of PID treatment is broad spectrum antibiotic (including anaerobic) coverage of the majority of likely pathogens, the most common being N. gonorrhoeae and C. trachomatis.5

- In women with mild to moderate severity PID and absence of pregnancy or TOA, IV and PO regimens have similar efficacy.3,5

- For outpatient treatment of PID, CDC guidelines recommend:5

- Ceftriaxone 250 mg IM (or other third generation cephalosporin) in single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg PO BID for 14 days, and consideration of addition of metronidazole 500 mg PO BID for 14 days for anaerobic coverage OR

- Cefoxitin 2 g IM in single dose and Probenicid 1bg PO in a single dose plus doxycycline 100 mg PO BID for 14 days, and consideration of metronidazole 500 mg PO BID for 14 days for anaerobic coverage

- For inpatient treatment of PID, CDC guidelines recommend5:

- Cefotetan 2 g IV every 12 hours plus doxycycline 100 mg PO or IV every 12 hours OR

- Cefoxitin 2 g IV every 6 hours plus doxycycline 100 mg PO or IV every 12 hours OR

- Clindamycin 900 mg IV every 8 hours plus gentamicin loading dose IV/IM 2 mg/kg followed by maintenance dose of 1.5 mg/kg every 8 hours.

- For doxycycline allergic patients, alternative regimens exist involving the addition of azithromycin to a cephalosporin or azithromycin with metronidazole.2

- According to CDC guidelines, whenever prescribing an alternate treatment option for PID, a culture should be obtained prior to initiating treatment.2,5

- IUDs in place do not need to be removed prior to initiating treatment for PID.3

- Treatment of PID in pregnancy should be done in consultation with an OBGYN.2

- Management of tubo-ovarian abscess:

- 60-80% resolve with antibiotic therapy alone.3

- Antibiotic therapy for TOA includes normal PID regimen with addition of anaerobic coverage with either metronidazole, clindamycin, or ampicillin/sulbactam.2,3

- Patient with clinical/radiological signs of TOA rupture OR patients who do not improve after 72 hours of treatment should be evaluated for CT/US-guided percutaneous drainage or other surgical interventions.2,3

Disposition:

- Little to no data exists regarding efficacy of outpatient vs inpatient treatment.3

- Indications for admission in PID:2,3

- Cannot exclude surgical emergency from differential diagnosis

- Pregnancy

- Failure of outpatient treatment, non-compliance with outpatient treatment

- Sepsis, clinical toxicity (fever, nausea, vomiting), inability to tolerate PO

- Tubo-ovarian abscess

- History of recent uterine instrumentation

- Immunosuppression

- Adolescence

- Pre-existing fertility issues

- For discharged patients, 72 hour follow-up should be arranged to ensure clinical improvement and compliance with prescribed regimen.

- Discharge instructions:

- Recommendation of abstinence from sexual activity until 1 week after completion of treatment for both partners and/or until symptoms have resolved.3

- Strong encouragement of partner evaluation and treatment.3

- Education on use of barrier contraceptives and “safe sex” techniques.3

- Follow-up in 3 days in ED or with primary care physician/OBGYN.

A sexually active 24-year-old woman presents to the emergency department with complaints of pelvic pain and discharge. Her vitals are within normal limits and her pregnancy test is negative. Exam is significant for cervical friability and white cervical discharge, as well as cervical motion and right adnexal tenderness. Pelvic ultrasound is performed showing a 4 cm mass near the right ovary. Which of the following would be the most appropriate treatment for this patient?

A) Cefoxitin IV x 3 days with doxycycline PO x 14 days

B) Ceftriaxone IM x 1 dose with azithromycin PO x 1 dose

C) Metronidazole PO x 7 days

D) Vancomycin IV x 5 days with clindamycin IV x 5 days

Answer: A

This patient presents with cardinal symptoms of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). Pelvic inflammatory disease is an ascending infection from the vagina or cervix to the upper reproductive tract in women. The primary symptoms of pelvic inflammatory disease are lower abdominal or pelvic pain, cervical tenderness or friability, and mucopurulent cervical discharge. The majority of cases are due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis. A complication of pelvic inflammatory disease can be tubo-ovarian abscess, an abscess of the fallopian tube or ovary. The presence of a tubo-ovarian abscess is an indication for inpatient treatment of pelvic inflammatory disease with cefoxitin and doxycycline.

Ceftriaxone and azithromycin (B) is the treatment for cervicitis. Cervicitis presents as cervical tenderness and discharge without ascending spread or abscess and is most commonly due to Neisseria gonorrhoeae or Chlamydia trachomatis. Metronidazole (C) would be indicated for a patient with trichomoniasis, which presents with a punctate cervical rash known as “strawberry cervix”, or bacterial vaginosis, presenting with a foul smelling white discharge which can be diagnosed by clue cells on wet prep. Vancomycin and clindamycin (D) would have poor activity against the common bacteria isolated from pelvic inflammatory disease.

FOAMed:

References:

- Chappell CA, Wiesenfeld HC. Pathogenesis, diagnosis, and management of severe pelvic inflammatory disease and tuboovarian abscess. Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 2012 Dec;55(4):893-903.

- Bugg CW, Taira T. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease: Diagnosis And Treatment In The Emergency Department. Emergency Medicine Practice. 2016 Dec;18(12):1-24.

- Shepherd SM, Weiss B, Shoff WH. Pelvic Inflammatory Disease. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e New York, NY: McGraw-Hill; 2016.

- Brunham RC, Gottlieb SL, Paavonen J. Pelvic inflammatory disease. The New England Journal of Medicine. 2015;(21):2039.

- Workowski KA, Bolan GA. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines, 2015. MMWR Recommendations & Reports. 2015;64(3):1.

- Mitchell C, Prabhu M. Pelvic inflammatory disease: current concepts in pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2013;27(4):793–809.