Author: Iosif Davidov, MD (EM/IM/CC/Ethics Fellow at North Shore/LIJ Northwell Health System) // Reviewed by: Sophia Görgens, MD (EM Physician, BIDMC, MA); Cassandra Mackey, MD (Assistant Professor of Emergency Medicine, UMass Chan Medical School); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK)

Welcome to EM@3AM, an emDOCs series designed to foster your working knowledge by providing an expedited review of clinical basics. We’ll keep it short, while you keep that EM brain sharp.

A 70-year-old female with a past medical history of hypertension, coronary artery disease s/p 2x drug eluting stent placement one month ago, atrial fibrillation on apixaban presents to the ED with weakness and lightheadedness.

Vital signs include BP 90/48, HR 122, T 98.3 F, RR 16, SpO2 97% on room air. The symptoms started roughly this morning and have progressively worsened. She also endorses some abdominal discomfort although the abdominal exam is benign. She appears pale. Lab work is concerning for a hemoglobin of 6.8 g/dl (decreased from 12 g/dl one month prior). She denies any gastrointestinal bleeding, and a rectal exam does not reveal any gross blood.

CT of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast reveals the following:

What is the diagnosis?

Answer: Spontaneous retroperitoneal hemorrhage

Epidemiology:

- Tends to occur more often in older patients (mean age at around 70 years) with a relatively even split between men and women.1

Risk Factors:1-4

- Spontaneous

- Anticoagulants (Apixaban, Rivaroxaban, etc.)

- Antiplatelets (aspirin, etc.)

- Older Age (median age of 70 years)1

- Abnormal vasculature/neoplasm of the kidney (e.g., angiomyolipomas)

- Iatrogenic

- Recent abdominal procedures

- Recent procedures involving cannulation of the femoral artery

- Ruptured AAA

Anatomy:

- Retroperitoneal hemorrhage (RPH) can be defined in three different zones: Central, lateral, and pelvic. A defined bleeding source is rarely found despite the zoning nomenclature, and this is more important for surgery and IR specialists in determining possible intervention.5

Clinical Presentation:1-3

- Variable presentation but may present with dropping hemoglobin/hematocrit without other findings in spontaneous cases.

- Most commonly will have pain:

- Abdominal pain (67%)

- Leg pain (24%)

- Back pain (21%)1

- Hemorrhagic shock

- History of recent procedures:

- Recent placement of femoral access

- Cardiac catheterizations

- Intra-abdominal surgeries

- Colonoscopies

- History of abdominal trauma or flank trauma

- Physical Exam Findings (unfortunately poor sensitivity and may take up to 24-48 hours to appear):

- Cullen’s sign (periumbilical ecchymosis)

-

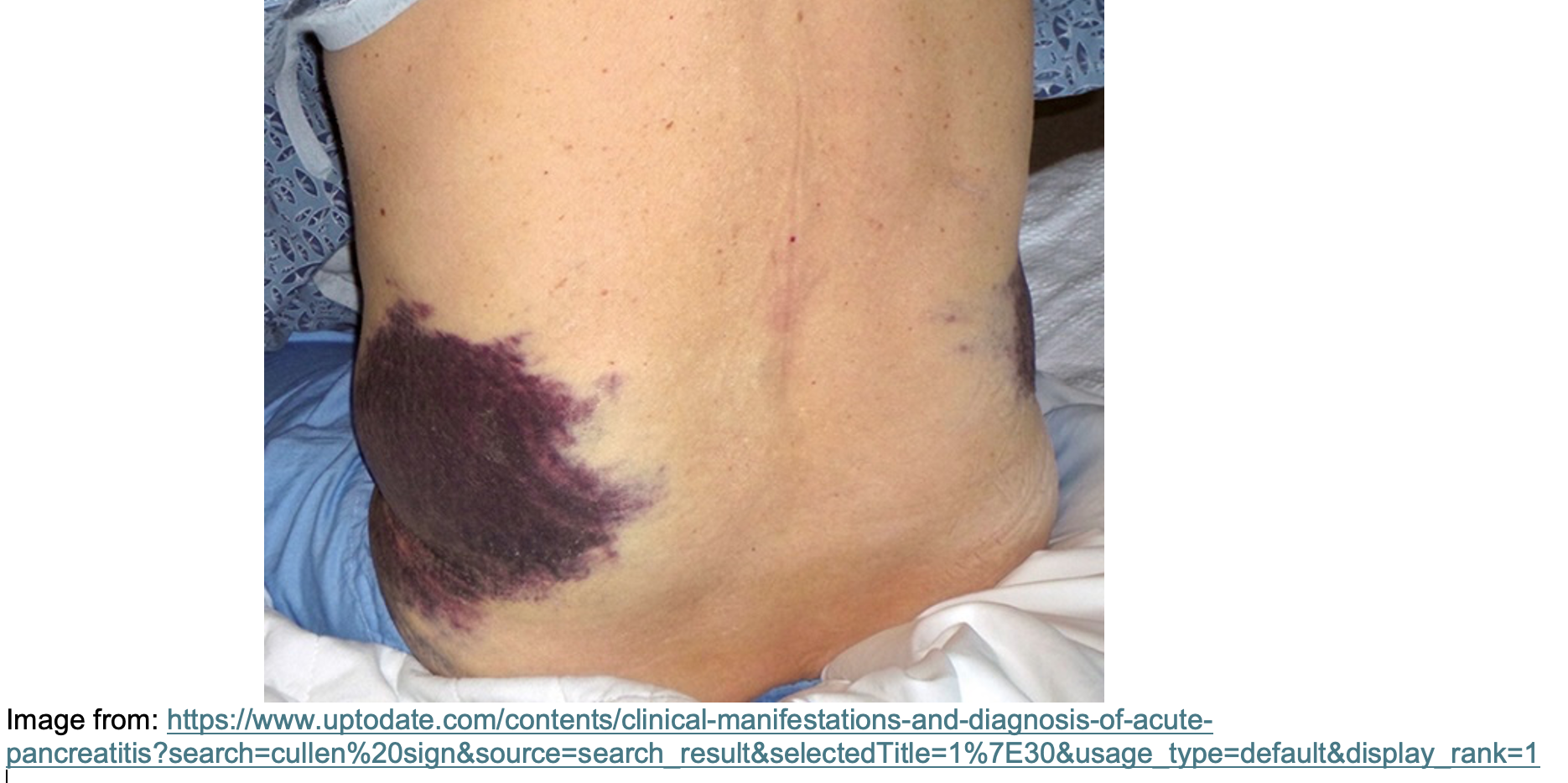

- Grey-Turner’s sign2 (flank ecchymosis)

-

- Fox’s Sign (proximal thigh ecchymosis)

- Bryant’s Sign (scrotal ecchymosis)

Evaluation:

- ABCs

- A trauma leading to a retroperitoneal hemorrhage likely is significant. Patients may arrive with other concomitant injuries such as head or spine injuries and may be critically ill.

- Imaging

- CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast or CT angiogram of the abdomen is the imaging modality of choice.

- Evaluates for cause of the bleeding (direct injury to a vessel for example) which would determine which service may intervene.

- CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast or CT angiogram of the abdomen is the imaging modality of choice.

- Laborator evaluation:

- CBC, CMP, lipase, type and screen, coagulation panel

Treatment:1-3

- Resuscitation with blood products as necessary for hemodynamic stability.

- Reversal of anticoagulation should be considered, especially in those with signs of hemodynamic instability.

- Majority of RPH will stabilize on their own and not require intervention.3

- If the patient is requiring large amounts of blood products or stabilizes and then worsens, then repeat labs and imaging to evaluate for expanding hematoma and possible site for intervention.

- All patients typically require admission for a new spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma for monitoring and decisions regarding when or if to restart anticoagulation.

Disposition:

- Consider ICU for many patients, especially if any signs of instability or repeatedly requiring blood products. Mortality can varies between 5-20%.1

- May need IR or surgical consultations for intervention.

Pearls:

- Retroperitoneal hematomas can occur spontaneously in our older population especially if on anticoagulation.

- Physical signs are unreliable for ruling out retroperitoneal bleeding and often do not show up until late in the presentation.

- Consider abdominal imaging with contrast in cases of acutely worsening hemoglobin without any explainable cause.

A 25-year-old man presents to the ED via EMS after he sustained a gunshot wound to the left flank. On examination, he has a circular wound, marked tenderness, and ecchymosis to the left flank. His initial vital signs include HR of 116 bpm, BP of 75/50 mm Hg, RR of 25/min, and SpO2 of 98% on room air. An eFAST is remarkable for trace-free fluid in the pelvis. After 1 L of normal saline and 2 units of packed red blood cells, the patient’s HR is 102 bpm and BP is 86/55 mm Hg. Chest X-ray and pelvis X-ray are unrevealing. What is the most appropriate next step in the management of this patient’s condition?

A) Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis with contrast

B) Measure serum hemoglobin and hematocrit

C) Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta

D) Transfer to the interventional radiology suite for embolization

E) Transfer to the operating room for retroperitoneal exploration

Answer: E

Retroperitoneal bleeding secondary to trauma can be associated with both penetrating and blunt trauma, usually to the abdomen or pelvis. There are three zones of the retroperitoneum. Zone I includes the central aspect of the retroperitoneum from the diaphragm extending inferiorly to the bifurcation of the aorta and thus includes the aorta, inferior vena cava, the branching of major arteries (e.g., renal vessels) from the aorta, the pancreas, and a portion of the duodenum. Zone II lies just lateral to zone I and extends from the diaphragm to the aortic bifurcation, including the perinephric regions bilaterally (i.e., the adrenal glands, kidneys, renal vessels, ureters, and ascending and descending colon). Zone III is inferior to the aortic bifurcation and includes the right and left internal and external iliac arteries and veins, distal ureters, sigmoid colon, and the rectum. Clinical features include abdominal or flank pain; ecchymosis to the flank, periumbilical region, proximal thighs, or scrotum; and hemorrhagic shock early in the disease course. Although a FAST exam may be positive in views of the pelvis if a zone III retroperitoneal bleeding is present, the test is validated for the detection of intraperitoneal bleeding and has a high false-negative rate for the detection of retroperitoneal bleeding.

The initial management of bleeding in these patients should be similar to other trauma patients, including evaluating and appropriately intervening on the patient’s airway, breathing, circulation, disability (e.g., Glasgow Coma Scale), and exposure (ABCDE). Management by retroperitoneal exploration varies by the suspected zone involved. In blunt or penetrating injury of zone I, the patient should undergo emergent exploration due to the risk of major vascular injury. In selective cases of traumatic injury to zone II, such as expanding hematoma, signs of active hemorrhage, or an inability to control hemorrhage with other methods (e.g., angioembolization in blunt trauma), the patient is a candidate for exploration. Management of zone III injuries differs between penetrating and blunt trauma. In cases of zone III penetrating trauma, exploration is indicated as a major vascular injury is at risk. For blunt injury to zone III, an alternative method for hemorrhage control should be pursued (e.g., angioembolization). In this patient with a penetrating posterior flank injury, trace-free fluid in the pelvis on eFAST, and ongoing signs of hemorrhagic shock despite fluid and blood product administration, transferring to the operating room for exploration is indicated, especially with high probability of zone III injury-related retroperitoneal bleeding.

Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis (A) with contrast would be indicated in hemodynamically stable patients to further elucidate the site of injury.

The time taken to measure serum hemoglobin and hematocrit (B) and await a result would delay definitive surgical control of likely ongoing hemorrhage given this patient’s incomplete response to fluid resuscitation. Additionally, hemoglobin results often lag in real-time when compared to the degree of acute hemorrhage.

Resuscitative endovascular balloon occlusion of the aorta (REBOA) (C) should be considered in patients at imminent risk of hemodynamic collapse and serves as a bridge to definitive surgical management. However, this patient’s response to fluid resuscitation, though only minimal to modest, indicates his ongoing bleeding is temporized with typical volume-mediated resuscitation. Additionally, no current high-quality literature exists regarding the definitive indications for REBOA placement.

Transfer to the interventional radiology suite for embolization (D) is indicated in patients with ongoing hemorrhage after a blunt injury to zone III, rather than a penetrating injury.

Further Reading:

Further FOAMed

- https://radiopaedia.org/articles/spontaneous-retroperitoneal-haemorrhage?lang=us

- https://litfl.com/retroperitoneal-haemorrhage/

References

- Sunga KL, Bellolio MF, Gilmore RM, Cabrera D. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma: etiology, characteristics, management, and outcome. J Emerg Med. 2012 Aug;43(2):e157-61. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2011.06.006. Epub 2011 Sep 10. PMID: 21911282.Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/21911282/

- Guldner GT, Smith T, Magee EM. Grey Turner Sign. [Updated 2024 Jan 9]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK534296/

- Sahu KK, Mishra AK, Lal A, George SV, Siddiqui AD. Clinical spectrum, risk factors, management and outcome of patients with retroperitoneal hematoma: a retrospective analysis of 3-year experience. Expert Rev Hematol. 2020 May;13(5):545-555. doi: 10.1080/17474086.2020.1733963. Epub 2020 Mar 3. Erratum in: Expert Rev Hematol. 2020 Jun;13(6):i. PMID: 32089021.

- Haskins, IA. Spontaneous retroperitoneal hematoma and rectus sheath hematoma. UpToDate. May 2024. (Accessed on 27 May 2024) https://www.uptodate.com/contents/spontaneous-retroperitoneal-hematoma-and-rectus-sheath-hematoma?search=retroperitoneal%20hemorrhage&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1#H4115548

- Mandell, SP. Overview of the diagnosis and initial management of traumatic retroperitoneal injury. UpToDate. June 2023. (Accessed on 27 May 2024) https://www.uptodate.com/contents/overview-of-the-diagnosis-and-initial-management-of-traumatic-retroperitoneal-injury?search=Overview%20of%20the%20diagnosis%20and%20initial%20management%20of%20traumatic%20retroperitoneal%20injury&source=search_result&selectedTitle=1%7E150&usage_type=default&display_rank=1