Today on the emDOCs cast with Brit Long, MD (@long_brit), we discuss necrotizing soft tissue infection pearls and pitfalls with Jess Pelletier, MD.

Jess is an emergency medicine physician and Education Fellow at Washington University School of Medicine. This second part looks at imaging and management of NSTI. For background, presentation, and laboratory evaluation, please see Part I.

Episode 66: NSTI Pearls and Pitfalls Part II

Pearl #5: Imaging has variable sensitivity for NSTI and can delay definitive operative management.

Pitfall: Relying on imaging to secure a diagnosis.

- NSTI is a clinical diagnosis; don’t wait for imaging to treat and speak with surgical specialist

- Plain radiographs may show gas, but sensitivity is 25-49%

- CT sensitivity is 80-88.5%, and specificity is 93.3-98%

- MRI has a sensitivity of 90-100% for NSTI when looking specifically at fascial thickening with T2 weighting

- MRI is limited in availability and requires a significant amount of time, usually making it impractical

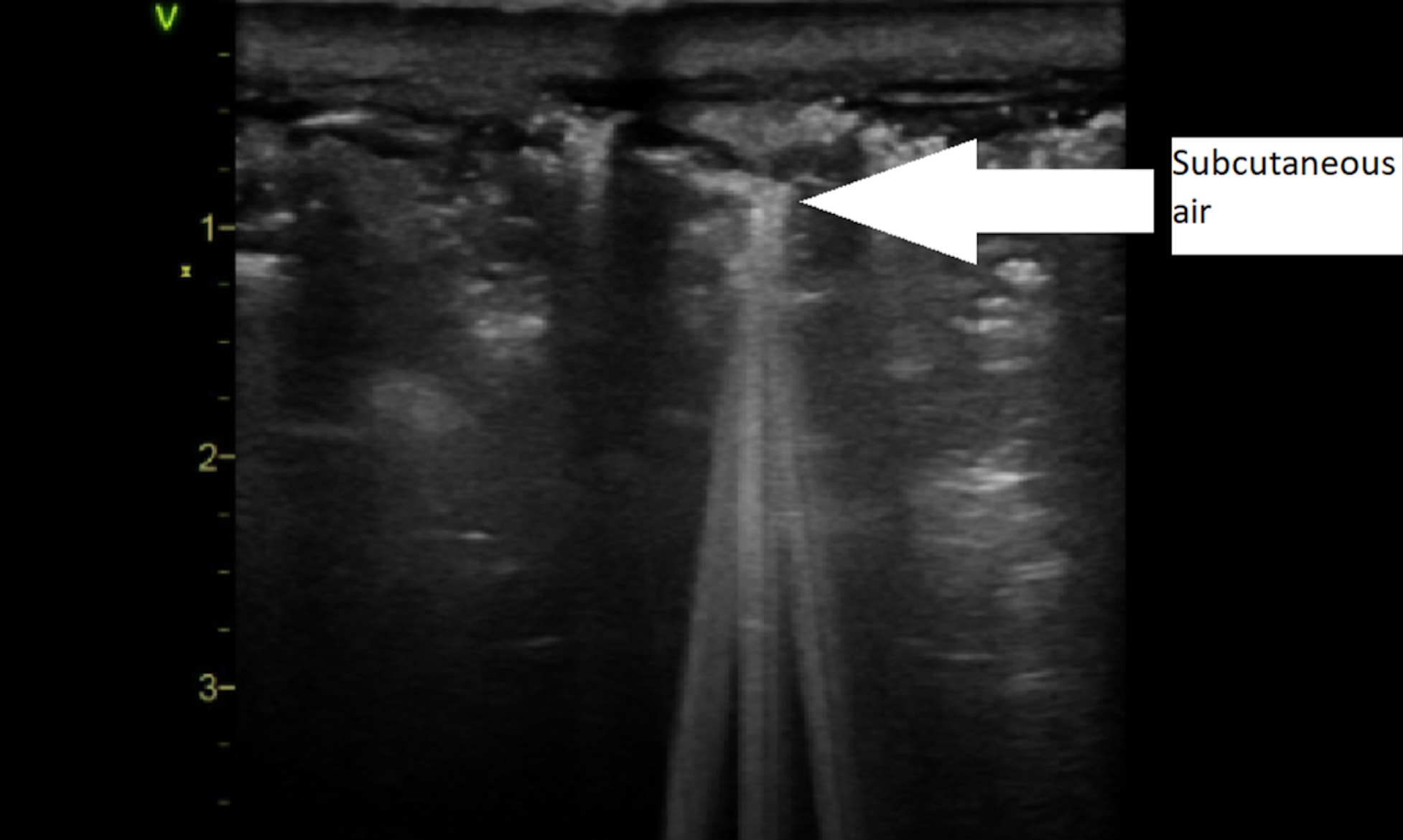

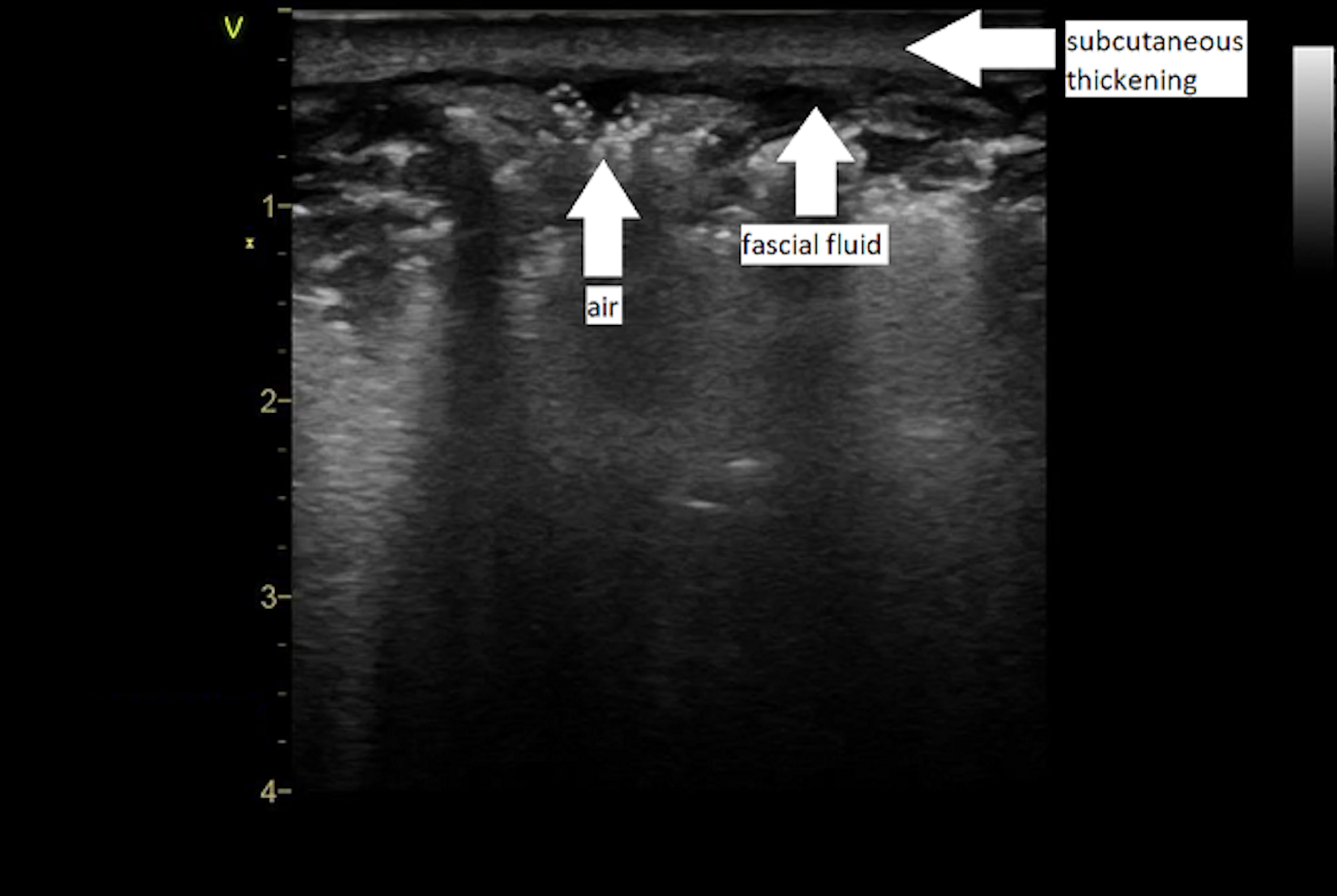

Pearl #6: POCUS may support the diagnosis of NSTI but is insufficient to exclude the condition.

Pitfall: Not utilizing POCUS in NSTI evaluation.

- POCUS can expedite the diagnosis

- “STAFF” mnemonic – subcutaneous thickening, air and fascial fluid

- Fluid accumulation is likely the most reliable POCUS finding for NSTI, with a sensitivity of 42.3%-88.2% and a specificity of 93.3%; look for over 2 mm of fascial fluid

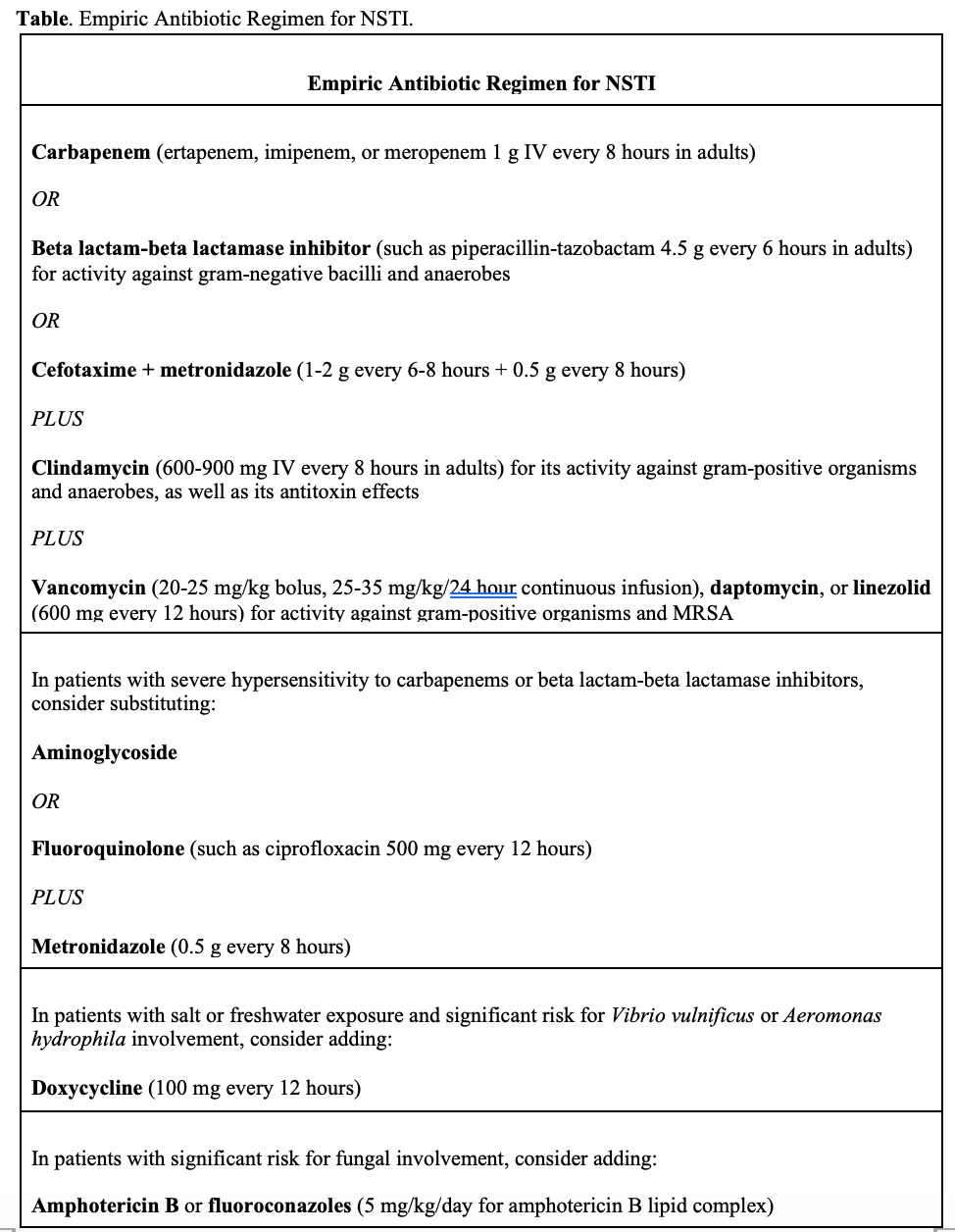

Pearl #7: Ensure the patient is hemodynamically optimized and has received antibiotics before transfer to the surgical suite.

Pitfall: Withholding antibiotic therapy if the diagnosis of NSTI is not entirely clear.

- ED management focuses on surgery consultation, aggressive fluid resuscitation, early broad-spectrum antibiotics, and initiation of vasopressors if fluid resuscitation does not maintain adequate perfusion

- Delays to the surgical suite may lead to worsened spread of the underlying infection and subsequent increase in risk for amputation, hospital length of stay, and mortality

- Adjunctive therapies include hyperbaric oxygen and intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIG), but they remain controversial

- There are not currently evidence-based guidelines to endorse the use of either of the adjuvant therapies, and they should be considered on a case-by-case basis when and if available

Pearl #8: A definitive diagnosis can be made at bedside with a scalpel in some patients.

Pitfall: Failing to explore all avenues to help the patient with a NSTI achieve early surgical consultation and source control.

- The pathophysiology of NSTI involves tissue death at the microvascular level with rapid spread along fascial planes

- Clinicians can perform bedside incision after local anesthesia to assess for ‘dishwater’ fluid or the ability to use one’s finger to ‘probe’ the necrotic tissue without impedance usually encountered with intact fascia

- Make a small incision (i.e. enough to insert a gloved finger) at the location of suspected NSTI (i.e. area is anesthetic, has dusky coloration, hemorrhagic bullae, or other signs of NSTI)

- Confirmed diagnosis with ‘dishwater’ appearing fluid or if finger can be used to explore the wound freely in all directions with minimal resistance

- While this may not be needed if general surgery is readily, this technique can confirm the diagnosis and expedite transfer for definitive surgical management in institutions where surgical consultation is not possible

Pearl #9: Source control in NSTI is the most significant factor in reducing mortality.

Pitfall: Failure to appreciate the importance of early and aggressive source control.

- In all NSTI subtypes, inflammation of local tissues leads to microvascular thrombosis, preventing host immune cells from responding to the infection and leading to decreased tissue oxygen and necrosis

- Once this microvascular thrombotic process has progressed and local tissue perfusion is poor, antibiotics cannot effectively penetrate the infected tissues

- Source control is paramount and the primary variable affecting patient outcome in NSTI

- One 2017 retrospective study found a 46% reduction in mortality with surgical intervention

- Survival in NSTI is optimal when patients are taken for surgical debridement within 6 hours of diagnosis, but a survival benefit is still seen as long as surgery is performed within 24 hours

Summary:

- NSTI is a deadly spectrum of soft tissue infection

- Variety of risk factors: immunocompromise, diabetes, renal/liver disease, also chronic illness or recent surgery, but a significant number won’t have any risk factor

- Patients can have various presentations; look carefully for vital sign abnormalities, and make sure to perform a full skin exam

- Patients don’t always have bullae or crepitus

- Red flags: pain out of proportion, rapidly expanding erythema, and pain beyond the margin of the erythema

- Don’t rely on labs or the LRINEC score to rule out the disease

- Imaging can help, but it isn’t 100%, even CT

- US can provide some important clues at the bedside with the STAFF mnemonic

- Treatment focuses on source control, resuscitation, broad-spectrum antibiotics, and source control

- If you’re concerned about the disease, get your surgeon down to the bedside

- Source control is the most important factor in the prognosis

References:

- Pelletier J, Gottlieb M, Long B, Perkins JC Jr. Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections (NSTI): Pearls and Pitfalls for the Emergency Clinician. J Emerg Med. 2022 Apr;62(4):480-491.

- Fernando SM, Tran A, Cheng W, et al. Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infection: Diagnostic Accuracy of Physical Examination, Imaging, and LRINEC Score: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Surg. 2019;269(1):58-65. doi:10.1097/SLA.0000000000002774

- Misiakos EP, Bagias G, Patapis P, Sotiropoulos D, Kanavidis P, Machairas A. Current Concepts in the Management of Necrotizing Fasciitis. Front Surg. 2014;1. doi:10.3389/fsurg.2014.00036

- Peetermans M, de Prost N, Eckmann C, Norrby-Teglund A, Skrede S, De Waele JJ. Necrotizing skin and soft-tissue infections in the intensive care unit. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020;26(1):8-17. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2019.06.031

- Montravers P, Snauwaert A, Welsch C. Current guidelines and recommendations for the management of skin and soft tissue infections. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2016;29(2):131-138. doi:10.1097/QCO.0000000000000242

- Stevens DL, Bryant AE. Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections. N Engl J Med. 2018;378(10):971. doi:10.1056/NEJMc1800049

-

Chen K-CJ, Klingel M, McLeod S, Mindra S, Ng VK. Presentation and outcomes of necrotizing soft tissue infections. Int J Gen Med. 2017;10:215-220. doi:10.2147/IJGM.S131768

- Yen Z-S, Wang H-P, Ma H-M, Chen S-C, Chen W-J. Ultrasonographic screening of clinically-suspected necrotizing fasciitis. Acad Emerg Med Off J Soc Acad Emerg Med. 2002;9(12):1448-1451. doi:10.1111/j.1553-2712.2002.tb01619.x

- Latifi R, Patel AS, Samson DJ, et al. The roles of early surgery and comorbid conditions on outcomes of severe necrotizing soft-tissue infections. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg. 2019;45(5):919-926. doi:10.1007/s00068-018-0958-z

- Wysoki MG, Santora TA, Shah RM, Friedman AC. Necrotizing fasciitis: CT characteristics. Radiology. 1997;203(3):859-863. doi:10.1148/radiology.203.3.9169717

- Martinez M, Peponis T, Hage A, et al. The Role of Computed Tomography in the Diagnosis of Necrotizing Soft Tissue Infections. World J Surg. 2018;42(1):82-87. doi:10.1007/s00268-017-4145-x

- Schmid MR, Kossmann T, Duewell S. Differentiation of necrotizing fasciitis and cellulitis using MR imaging. Am J Roentgenol. 1998;170(3):615-620. doi:10.2214/ajr.170.3.9490940

- Hopkins KL, Li KC, Bergman G. Gadolinium-DTPA-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging of musculoskeletal infectious processes. Skeletal Radiol. 1995;24(5):325-330. doi:10.1007/BF00197059

- Hakkarainen TW, Kopari NM, Pham TN, Evans HL. Necrotizing soft tissue infections: Review and current concepts in treatment, systems of care, and outcomes. Curr Probl Surg. 2014;51(8):344-362. doi:10.1067/j.cpsurg.2014.06.001

- Kehrl T. Point-of-Care Ultrasound Diagnosis of Necrotizing Fasciitis Missed By Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J Emerg Med. 2014;47(2):172-175. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2013.11.087

- Shyy W, Knight RS, Goldstein R, Isaacs ED, Teismann NA. Sonographic Findings in Necrotizing Fasciitis: Two Ends of the Spectrum. J Ultrasound Med. 2016;35(10):2273-2277. doi:10.7863/ultra.15.12068

- Testa A, Giannuzzi R, De Biasio V. Case report: role of bedside ultrasonography in early diagnosis of myonecrosis rapidly developed in deep soft tissue infections. J Ultrasound. 2016;19(3):217-221. doi:10.1007/s40477-015-0155-4

- Lin C-N, Hsiao C-T, Chang C-P, et al. The Relationship Between Fluid Accumulation in Ultrasonography and the Diagnosis and Prognosis of Patients with Necrotizing Fasciitis. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2019;45(7):1545-1550. doi:10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2019.02.027

- Hadeed G, Smith J, O’Keeffe T, et al. Early surgical intervention and its impact on patients presenting with necrotizing soft tissue infections: A single academic center experience. J Emerg Trauma Shock. 2016;9(1):22. doi:10.4103/0974-2700.173868

- Stevens DL, Bisno AL, Chambers HF, et al. Practice guidelines for the diagnosis and management of skin and soft tissue infections: 2014 update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin Infect Dis Off Publ Infect Dis Soc Am. 2014;59(2):e10-52. doi:10.1093/cid/ciu444

- Amphotericin B (Lipid Complex) (Lexi-Drugs). In: Lexicomp. ; 2021. http://online.lexi.com/?cesid=6BqX1UzCJn6&searchUrl=%2Flco%2Faction%2Fsearch%3Fq%3Damphotericin

- Levett DZ, Bennett MH, Millar I. Adjunctive hyperbaric oxygen for necrotizing fasciitis. Cochrane Emergency and Critical Care Group, ed. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Published online January 15, 2015. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007937.pub2

- Kadri SS, Swihart BJ, Bonne SL, et al. Impact of Intravenous Immunoglobulin on Survival in Necrotizing Fasciitis with Vasopressor-dependent Shock: A Propensity-Score Matched Analysis from 130 US Hospitals. Clin Infect Dis. Published online December 29, 2016:ciw871. doi:10.1093/cid/ciw871

- Wang T-L, Hung C-R. Role of tissue oxygen saturation monitoring in diagnosing necrotizing fasciitis of the lower limbs. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;44(3):222-228. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.03.022

- Singer M, Deutschman CS, Seymour CW, et al. The Third International Consensus Definitions for Sepsis and Septic Shock (Sepsis-3). JAMA. 2016;315(8):801. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.0287

- Martínez ML, Ferrer R, Torrents E, et al. Impact of Source Control in Patients With Severe Sepsis and Septic Shock*: Crit Care Med. 2017;45(1):11-19. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002011

- McHenry CR, Piotrowski JJ, Petrinic D, Malangoni MA. Determinants of Mortality for Necrotizing Soft-Tissue Infections: Ann Surg. 1995;221(5):558-565. doi:10.1097/00000658-199505000-00013

- Freischlag JA, Ajalat G, Busuttil RW. Treatment of necrotizing soft tissue infections. The need for a new approach. Am J Surg. 1985;149(6):751-755. doi:10.1016/s0002-9610(85)80180-x

- Bucca K, Spencer R, Orford N, Cattigan C, Athan E, McDonald A. Early diagnosis and treatment of necrotizing fasciitis can improve survival: an observational intensive care unit cohort study: Early diagnosis and treatment of NF. ANZ J Surg. 2013;83(5):365-370. doi:10.1111/j.1445-2197.2012.06251.x