Authors: Christopher Whiting, MD (EM Resident Physician, University of Vermont) and Joseph Kennedy (EM Attending Physician, University of Vermont) // Reviewed by: Joshua Lowe (EM Attending Physician, USAF), Marina Boushra (EM-CCM Attending Physician, Cleveland Clinic Foundation); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 57-year-old man with a past medical history of hypertension and tobacco use presents to the emergency department (ED) with five days of abdominal pain. He describes the pain as a gradually worsening pressure-like discomfort distributed across his entire abdomen. He reports distension and the sensation of fullness. These symptoms progressed to significant nausea and several bouts of vomiting shortly before arrival. The patient also reports poor appetite and weight loss over the prior month. He has no significant surgical history. On physical examination, the patient has a markedly distended abdomen that is tender to palpation in all four quadrants, tympanitic on percussion, but is overall soft. His rectal vault is empty. His vital signs on arrival are HR 125 BPM, BP 165/118 mmHg, T 37.2 °C, and oxygen saturation 96% on room air. There is significant concern for an obstructive bowel process. What are the next steps in his evaluation?

Introduction

Large bowel obstruction (LBO) represents approximately 25% of all presentations of bowel obstruction.1 While less common than small bowel obstruction (SBO), obstruction of the large bowel is more likely to be a surgical emergency and is often associated with a serious underlying condition.1-3 This is because most LBOs are closed-loop obstructions, with the pathologic obstruction at the distal end and the ileocecal valve as a proximal end point. This can rapidly lead to significant dilatation, bowel ischemia/necrosis, and perforation. Conversely, SBOs are usually open-loop obstructions that can be decompressed from above.3 The most common cause of LBO is colorectal cancer (CRC), with recent data demonstrating that more than 60% of presentations are related to malignancy.1 The most common causes of non-cancer-related LBO are cecal and sigmoid volvulus. More rare causes include incarcerated hernia, stricture, inflammatory conditions, stercoral colitis, and adhesions.2-3

Risk Factors

CRC is the most common underlying etiology of LBO.1 Therefore, the risk factors for LBO closely parallel those of CRC, most notably advanced age, poor diet, heavy alcohol or tobacco use, and family history of CRC.4 Despite the widespread availability of screening for CRC, LBO is still the initial presenting symptom in nearly one-third of patients and, therefore, lack of a previous diagnosis of CRC does not reduce the risk of LBO.5 Recent evidence indicates regression in the age of presentation for CRC, with new screening guidance starting at age 45, this diagnosis should also be considered in younger patients.6 Other notable risk factors include a history of inflammatory bowel disease and chronic constipation.1 In the case of cecal volvulus, long-distance running is a unique risk factor.7 While post-operative adhesive disease is also a risk factor, it is far less commonly implicated in LBO compared to SBO.1

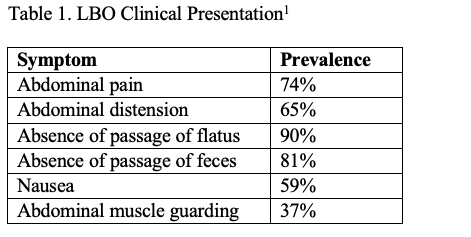

Presentation

The presentation of LBO varies but classically includes abdominal pain (74%), distension (65%), nausea (59%) and the absence of passage of flatus or feces (90% and 81%) (Table 1).1 Antecedent symptoms may be helpful in determining the etiology and distinguishing LBO from other suspected diagnoses. Patients with colorectal malignancy may share a recent history of weight loss, small-diameter (pencil) stools, or rectal bleeding.5 Chronic constipation may raise suspicion for stercoral colitis, while sudden-onset severe abdominal pain should point the clinician towards volvulus or incarcerated hernia. Signs and symptoms of peritonitis, hypotension, tachycardia out of proportion to pain, or fever should raise suspicion for perforation, which is a surgical emergency.8 LBO may not be easily distinguished from SBO, pseudo-obstruction, ileus, or other acute abdominal complaints on history and physical examination alone, as they share many of the same presenting symptoms.

Evaluation

Imaging

A definitive diagnosis of LBO requires imaging, most often a computed tomography (CT) scan with intravenous (IV) contrast. This also serves as a tool for surgical planning.2,3,5 A CT scan with IV contrast is reported as 96% sensitive and 93% specific for LBO.3,14 There are currently no good studies of enteric or rectal contrast administration in the evaluation of LBO and there are no society recommendations for its use. Therefore, as enteric contrast delays testing, can lead to complications of aspiration or vomiting. and is poorly tolerated by patients with obstruction, it should not be a routine part of the ED evaluation for LBO unless it is critical for another diagnosis on the differential.9,10 CT findings of LBO include diffuse proximal colon dilation with an abrupt transition point and collapsed distal colon (Figure 1). Small bowel dilation may also be seen.3,14

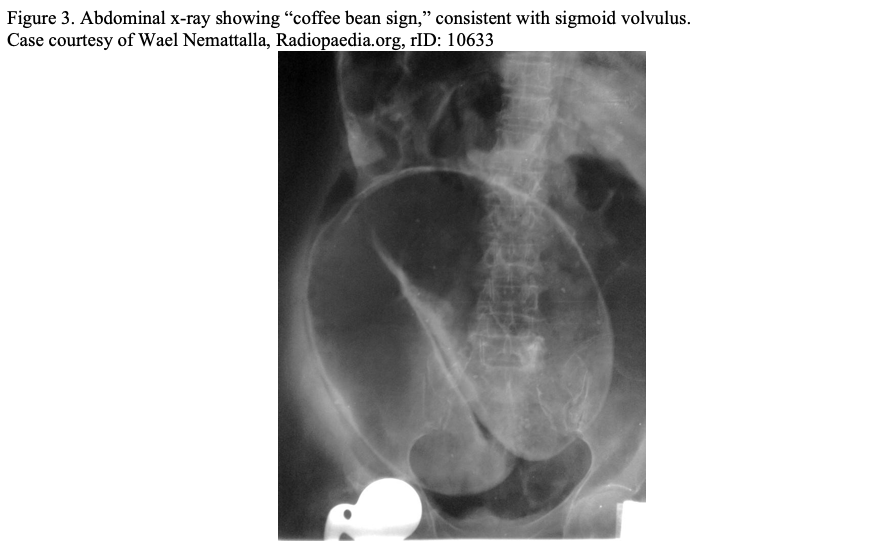

Plain radiographs can be utilized in cases of hemodynamic instability or anticipated significant delay to CT imaging to evaluate for free air, free fluid, or colonic dilatation (Figure 2). In certain disease processes, such as sigmoid and cecal volvulus, plain radiographs can be diagnostic (Figure 3). However, a negative plain radiograph should not be used to rule out obstruction and cannot usually determine the etiology of colonic dilatation. 3 Multiple mimics of LBO such as adynamic ileus, acute colonic pseudo-obstruction, or toxic megacolon can be difficult to distinguish on plain film and are better defined on CT.3 Point of care ultrasound (POCUS) can be highly sensitive for free fluid and pneumoperitoneum when used by a trained physician in the appropriate patient population. 9 POCUS has utility for the critically ill patient who may not be appropriate for CT to assess for perforation.9 In low resource settings, POCUS can be utilized to evaluate for LBO; unfortunately, not enough data exists to accurately judge its positive and negative predictive value.9

Fluoroscopic contrast enema can be a useful imaging modality to delineate LBO from pseudo-obstruction, as water-soluble contrast can usually distinguish a transition point from diffuse colonic dilation without a clear transition point. However, its practical use in the ED evaluation is limited due to personnel burden, patient discomfort, and patient selection (patients must be able to tolerate lying and turning on the fluoroscopy table to fully visualize the colon).3

Labs

There are no laboratory tests that are specific or sensitive for bowel obstruction. However, routine labs, including a complete blood count and metabolic panel, can guide resuscitative efforts preoperatively and may identify clinically relevant abnormalities associated with obstruction, including electrolyte changes, renal injury from hypoperfusion, or anemia secondary to underlying malignancy. In the critically ill patient, a type and screen and coagulation studies may be helpful. Lactate and procalcitonin have both been studied as diagnostic tools for bowel ischemia.11,12 Procalcitonin levels above 1 ng/mL on presentation have been shown to be highly sensitive, but not specific, for bowel ischemia and necrosis at the time of surgery in patients with confirmed LBO.12 Additionally, levels below 0.25 ng/mL have strong negative predictive value for ischemia and necrosis, 83% and 95% respectively.12

Management

LBO often warrants emergent or urgent surgical intervention which requires a multidisciplinary approach, often involving specialists in emergency medicine, general surgery, and gastroenterology. Bowel perforation demonstrated by CT, hard signs of peritonitis, or an overall toxic appearance warrant emergent surgical consultation. Measures to optimize the patient for surgical intervention and treat shock, including antibiotics and fluid resuscitation, are associated with improved outcomes in these patients.5 Non-perforated obstruction due to malignancy will usually be managed with urgent surgery.5 Depending on the location of the tumor, this may be a partial colonic resection with primary anastomosis or colostomy formation.5 Cecal volvulus should be managed with emergent colectomy or cecopexy if there is concern for ischemia. Otherwise, it is usually managed surgically within a few days.13

The management of sigmoid volvulus differs from other etiologies of LBO. Initial management can include endoscopic detorsion followed by delayed elective sigmoid colectomy.13 Depending on the hospital staffing, this may be a gastroenterology consult or a surgical consult. It is important to assess the patient’s medical comorbidities, as an endoscopic detorsion is a procedure occasionally performed in the ED by a gastroenterologist with an emergency physician providing support for sedation and monitoring. Symptomatic management for patient comfort with antiemetics and analgesics, while definitive management is undertaken, should not be overlooked.

Case Conclusion

The patient undergoes a CT scan with IV contrast that shows a left-sided mass within the sigmoid colon concerning for CRC. The patient receives 1 liter of lactated ringer’s solution while awaiting a surgical consultation. Surgery recommends NG decompression and that the patient remain nothing by mouth (NPO). The next morning, the patient undergoes a sigmoid colectomy with primary anastomosis. Based on surgical pathology, the patient is found to have CRC and is referred to an interdisciplinary oncology team.

Pearls

-LBO is often associated with a serious underlying condition such as CRC and is not usually successfully managed with non-operative measures.

-A CT scan with IV contrast is the test of choice in suspected LBO as it is highly sensitive and specific. However, surgical consultation should not be delayed while waiting for imaging in a patient who is in shock, appears toxic, or has signs of peritonitis.

-In hemodynamically unstable patients, perforation should be suspected. In these cases, CT may not be feasible and a plain radiograph showing free air or bedside US showing free fluid may be useful to confirm serious abdominal pathology prior to transfer to the operating room.

References

- Markogiannakis H, Messaris E, Dardamanis D, Pararas N, Tzertzemelis D, Giannopoulos P, Larentzakis A, Lagoudianakis E, Manouras A, Bramis I. Acute mechanical bowel obstruction: clinical presentation, etiology, management and outcome. World J Gastroenterol. 2007 Jan 21;13(3):432-7. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v13.i3.432. PMID: 17230614; PMCID: PMC4065900.

- Kothari K, Friedman B, Grimaldi GM, Hines JJ. Nontraumatic large bowel perforation: spectrum of etiologies and CT findings. Abdom Radiol (NY). 2017;42(11):2597-2608.

- Jaffe T, Thompson WM. Large-Bowel Obstruction in the Adult: Classic Radiographic and CT Findings, Etiology, and Mimics. 2015;275(3):651-663.

- Sawicki T, Ruszkowska M, Danielewicz A, Niedźwiedzka E, Arłukowicz T, Przybyłowicz KE. A Review of Colorectal Cancer in Terms of Epidemiology, Risk Factors, Development, Symptoms and Diagnosis.Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(9):2025. Published 2021 Apr 22. doi:10.3390/cancers13092025

- Pisano M, Zorcolo L, Merli C, et al. 2017 WSES guidelines on colon and rectal cancer emergencies: obstruction and perforation. World J Emerg Surg. 2018;13:36. Published 2018 Aug 13.

- Patel SG, Murphy CC, Lieu CH, Hampel H. Early age onset colorectal cancer.Adv Cancer Res. 2021;151:1-37. doi:10.1016/bs.acr.2021.03.001

- Bauman BD, Witt JE, Vakayil V, et al. Cecal volvulus in long-distance runners: A proposed mechanism. Am J Emerg Med. 2019;37(3):549-552. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2018.07.045

- Gorgens et al., Bowel Perforation: ED Presentations, evaluation and management. EMDocs. 2021 Nov. http://www.emdocs.net/bowel-perforation-ed-presentations-evaluation-and-management/

- Expert Panel on Gastrointestinal Imaging, Chang KJ, Marin D, et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria® Suspected Small-Bowel Obstruction.J Am Coll Radiol. 2020;17(5S):S305-S314. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2020.01.025

- Nelms DW, Kann BR. Imaging Modalities for Evaluation of Intestinal Obstruction. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2021;34(4):205-218. doi:10.1055/s-0041-1729737

- Cosse C, Sabbagh C, Kamel S, Galmiche A, Regimbeau JM. Procalcitonin and intestinal ischemia: a review of the literature.World J Gastroenterol. 2014;20(47):17773-17778. doi:10.3748/wjg.v20.i47.17773

- Markogiannakis H, Memos N, Messaris E, et al. Predictive value of procalcitonin for bowel ischemia and necrosis in bowel obstruction. Surgery. 2011;149(3):394-403. doi:10.1016/j.surg.2010.08.007

- Kapadia MR. Volvulus of the Small Bowel and Colon. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2017;30(1):40-45. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1593428

- Frager D, Rovno HD, Baer JW, Bashist B, Friedman M. Prospective evaluation of colonic obstruction with computed tomography. Abdom Imaging. 1998;23(2):141-146. doi:10.1007/s002619900307

1 thought on “Large bowel obstruction: ED presentation, evaluation, and management”

Pingback: LITFL Update 014 • LITFL • Newsletter