Authors: Noah Kronk, MS-4 (University of Missouri-Columbia); Jessica Pelletier, DO, MHPE (APD, EM Attending Physician, University of Missouri-Columbia, USA) // Reviewed by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case

A 30-year-old female presents to the emergency department (ED) with fever, fatigue, and an extensive rash. Five days prior, she began experiencing fever, headache, and myalgias, followed by swollen lymph nodes and a rapidly progressing rash. The rash started as macules on her face and soon spread to her trunk, arms, and legs, evolving into pustular, umbilicated lesions with central crusting. She reports no recent travel history or known contacts with similar symptoms but mentions that she shared a residence with multiple people, some of whom had unexplained rashes in recent weeks.

On examination, the patient appears fatigued with visible distress due to discomfort from the rash. Vital signs reveal a temperature of 38.4°C, heart rate of 112 bpm, respiratory rate of 22 breaths/minute, and blood pressure of 100/68 mmHg. Her skin shows extensive pustular lesions on her face, hands, and forearms, some of which have begun to crust over. Palpable lymphadenopathy is noted in the cervical, axillary, and inguinal regions. Initial laboratory tests are unremarkable except for mild leukocytosis. Given her presentation, mpox is suspected, and confirmatory PCR testing is performed. Supportive care and infection control measures are initiated.

Background

Mpox (formerly known as monkeypox) is a DNA virus within the Orthopoxvirus genus, part of the Poxviridae family. The mpox virus has two primary clades: the West African clade and the Central African (Congo Basin) clade, each further divided into subclades.1 The Central African clade (clade 1 mpox) is known to be more virulent and associated with greater illness severity and higher fatality rate, around 10%, compared to the 4% fatality rate of the West African clade (clade 2 mpox).1

Mpox is considered endemic to countries in Central and West Africa and was first detected in humans in 1970 in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In July 2022, mpox was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) after a clade 2 strain began spreading rapidly across 110 countries. This PHEIC status was lifted in May 2023 following a consistent global decline in case numbers.2 Beginning in January 2023, the DRC documented a record number of annual suspected cases of clade 1 mpox, specifically classified as Clade 1b. By 2024, over 17,000 suspected cases (2,863 confirmed) were documented across Africa, with the majority in the DRC. The outbreak spread to four additional African countries, leading the Africa CDC to declare it a Public Health Emergency of Continental Security. In August 2024, the World Health Organization (WHO) also classified the outbreak as a PHEIC.3 On November 16, 2024, health officials reported the first U.S. case of the clade 1b mpox strain treated in northern California, which the affected individual acquired via travel to the eastern region of DRC.4

Outbreaks involving different mpox subclades can vary significantly in their characteristics, including the populations they affect, modes of transmission, and associated mortality rates. Each subclade may demonstrate unique patterns in terms of spread and severity, which can influence public health responses and management strategies. During the 2022 clade 2 mpox outbreak, the majority of cases occurred among men who have sex with men (MSM), including individuals with multiple sexual partners and sex workers. This demographic was predominantly affected due to the transmission dynamics linked to close, prolonged physical and sexual contact. In contrast, the 2024 clade 1b outbreak has demonstrated a broader demographic impact, infecting a wider range of individuals, including heterosexual populations and children.5

Sexual contact was the primary mode of transmission during the clade 2 outbreak and continues to play a significant role in clade 1b cases. However, clade 1b has also been characterized by notable zoonotic transmission and household contact. Rodents, including African rope squirrels, tree squirrels, and Gambian pouched rats, are recognized as the natural hosts of the monkeypox virus. Human infection often results from bites, scratches, or contact with an infected animal’s fluids or lesions. In Africa, hunting and consuming bushmeat, particularly rodents and non-human primates, significantly drive zoonotic transmission, with improper handling during preparation further increasing infection risk.6 Notably, children in endemic regions have been disproportionately affected by clade 1b, accounting for 67% of reported cases and 78% of deaths in individuals aged 15 and younger.5

Mpox is primarily transmitted to humans through direct contact with infected animals, particularly rodents and primates, or through close contact with infected individuals or contaminated objects. Human-to-human spread can occur via respiratory droplets, bodily fluids, or contact with skin lesions.7 After exposure, the virus enters the body through mucous membranes and spreads through immune cells and lymph nodes, entering a latent period lasting up to two weeks. Symptoms then begin with fever, chills, headache, muscle pain, and swollen lymph nodes. A rash follows, starting on the face and spreading across the body, evolving from papules to vesicles, pustules, and eventually crusts that heal over 2-4 weeks, often leaving scars.8 Emergency clinicians must be able to recognize these classic skin lesions so that appropriate testing is ordered in the ED and the patient is instructed to isolate themselves to prevent further spread of disease.

Evaluation

History and Physical Exam

Gathering a detailed clinical history is essential for assessing suspected mpox cases and refining the differential diagnosis. Important factors include recent travel to endemic areas, known contact with infected individuals, the onset and nature of symptoms, sexual history, and any prior smallpox vaccination, as this vaccine can significantly lower the risk of severe mpox.9,10 Early symptoms of mpox are often nonspecific and generally appear within the first five days. Symptoms often begin with fever, typically the first sign, followed by muscle aches, fatigue, headache, sore throat, and cough.10

Physical examination findings for mpox typically include lymphadenopathy, especially in the neck, groin, and submandibular areas within the first six days of illness. The characteristic rash, which can show lesions at similar or varying stages of development, usually begins with pruritic or painful, firm, umbilicated lesions on the face around days 3–11. The rash then often spreads to the chest, limbs, hands, and feet, and may involve the oral mucosa and conjunctiva.10 A careful genital exam is crucial, as lesions may be localized there, as seen in many cases from the 2022 outbreak. Lesions start as macules and progress every 1–2 days: they evolve into papules (around day 3), then vesicles with clear fluid (days 4–5), and finally into pustules containing yellow fluid (days 6–7). These lesions then crust over and form scabs by days 7–14.11 While lesions generally progress at the same rate, they may sometimes appear in different stages across the body.

Figure 1. Mpox rash progression. Source: UK government, OGL 3 <http://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3>, via Wikimedia Commons. This file is licensed under the United Kingdom Open Government Licence v3.0

Figure 2. Mpox penile lesions. Source: By Dr Graham Beards – Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=122959447

Less common physical exam findings associated with mpox complications can include secondary skin infections, proctitis, bronchopneumonia, diarrhea and dehydration, eye-related issues, and, in very rare cases, encephalitis.12 Due to these potential complications, conducting thorough neurologic, ophthalmologic, and cardiopulmonary examinations is essential.

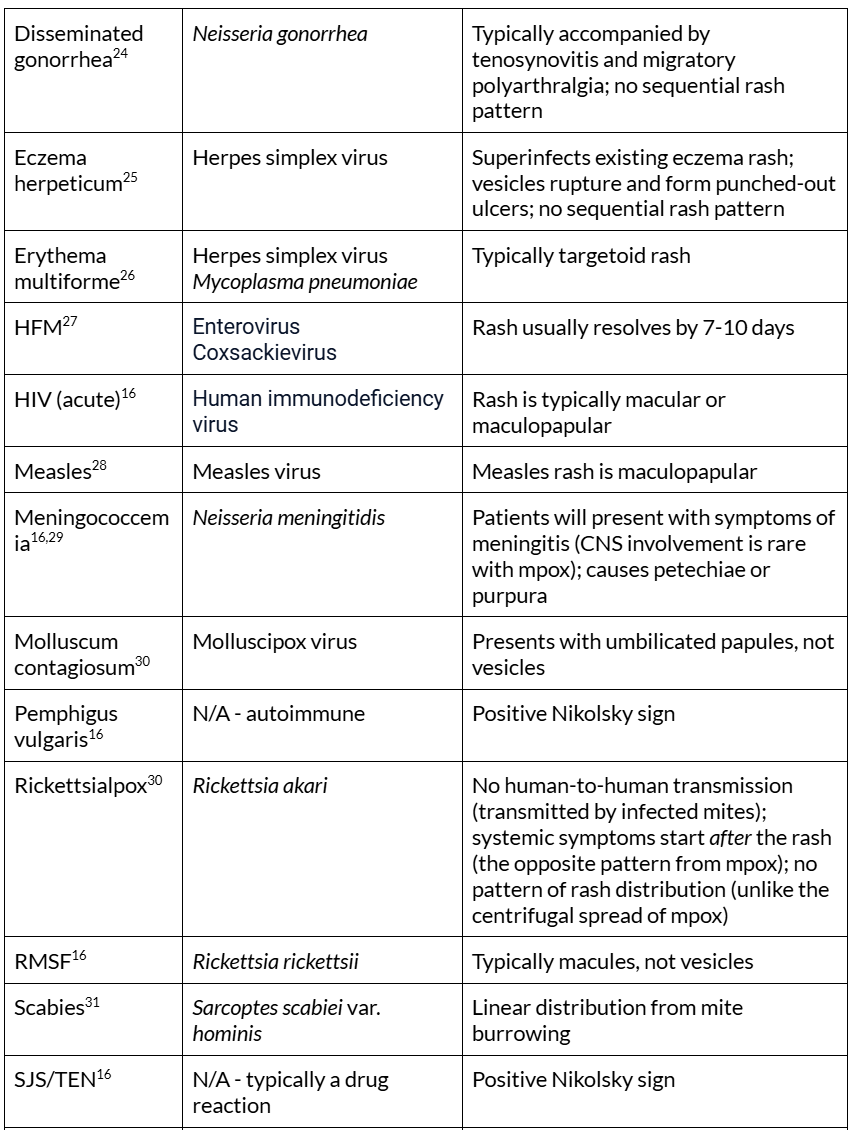

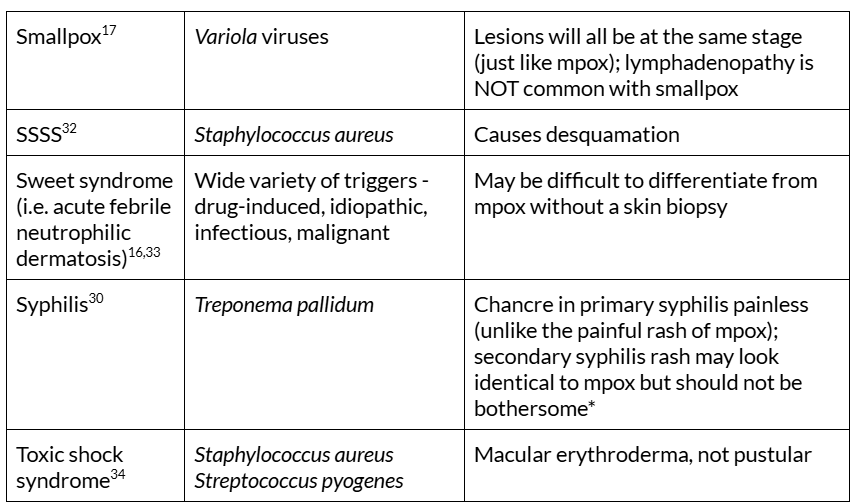

Table 1. Mpox rash mimics. Table adapted from: Long B, Liang SY, Carius BM, et al. Mimics of Monkeypox: Considerations for the emergency medicine clinician. The American Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2023;65:172-178. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.01.007

CNS = central nervous system, HFM = hand, foot, and mouth disease, HIV = human immunodeficiency virus, spp = species, SJS = Stevens-Johnson syndrome, SSSS = Staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome, TEN = toxic epidermal necrolysis. *Condylomata lata is a rash feature specific to secondary syphilis but is not always present30

Labs

To aid in narrowing down the differential diagnosis and assessing for severe manifestations of mpox, laboratory testing is recommended, including a complete blood count (CBC), electrolyte panel, and liver and kidney function tests.12 While these tests can help monitor the patient’s overall health status and detect complications, there are no specific laboratory findings directly indicative of mpox itself.

The WHO recommends PCR or real-time PCR as the primary diagnostic tools for mpox due to their high sensitivity, specificity, and efficiency.35 Standard PCR assays demonstrate over 96% sensitivity and 94% specificity, making them both rapid and reliable for accurate diagnosis.36,37 Samples should be collected from lesions or exudates, ideally from open lesions. Two swabs should be acquired from at least three different lesions, placing each swab in a dry, sterile container. Different types of lesions should be stored separately, while samples from similar lesions can be grouped together. Samples should be refrigerated or frozen until they are ready for testing.35

The World Health Organization (WHO) recently expanded its Emergency Use Listing (EUL) to include multiple rapid polymerase chain reaction (PCR) tests for mpox diagnostics. These include the ABT Molecular Diagnostics Emergency Use PCR and the GeneProof Mpox Virus PCR Kits, designed to provide accurate and timely detection of mpox, especially in resource-limited settings. The Xpert Mpox test, tailored for detecting mpox virus clade 2, is user-friendly and delivers results in under 40 minutes, making it ideal for urgent clinical and public health responses. Additionally, the cobas MPXV assay offers the capability to detect both mpox clades, delivering results within two hours. Its ability to process multiple samples simultaneously makes it a practical choice for high-volume laboratories.38

Other diagnostic methods are available, such as isothermal amplification techniques, CRISPR-based diagnostics, electron microscopy, viral culture, and immunological assays. Although these approaches offer alternative pathways, each comes with unique advantages and limitations, which are beyond the scope of this article.39

All patients evaluated for mpox should also be tested for sexually transmitted infections such as gonorrhea, chlamydia, syphilis, and HIV if their infection is suspected of having been sexually acquired. High rates of coinfection with these STIs were documented in several cohorts during the 2022 mpox outbreak.40-41

Management

Currently, no treatments are specifically approved for mpox infections. For most patients with intact immune systems and no underlying skin conditions, supportive care and pain management are typically sufficient for recovery without the need for additional medical intervention. Patients who do not require hospitalization can be discharged with instructions to strictly quarantine from others, including mammals (dogs, cats, etc.), as these animals can contribute to the spread of disease.42 Isolation should continue until all scabs have fallen off and new skin has formed.43

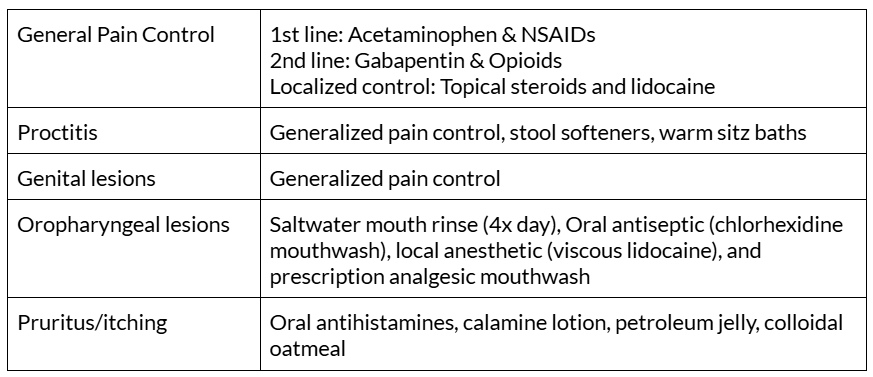

As shown in Table 1, the CDC recommends acetaminophen or NSAIDs for general pain relief, with gabapentin or opioids reserved for more severe cases. Localized pain, such as from proctitis or oropharyngeal lesions, can be treated with topical steroids, lidocaine, and saltwater rinses, while sitz baths and stool softeners alleviate discomfort during bowel movements. For pruritus, antihistamines and soothing agents like calamine lotion or colloidal oatmeal are effective in reducing irritation and promoting comfort.

Table 2. Management of pain related to mpox. Adapted from CDC: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Clinical Considerations for Pain Management.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-care/pain-management.html

For special populations, as discussed in the following paragraph, the CDC may recommend medications from the Strategic National Stockpile. As shown in Table 2, these include Tecovirimat (TPOXX), Cidofovir (Vistide), Vaccinia Immune Globulin Intravenous (VIGIV), and Brincidofovir (Tembexa).44 While there are no clinical trials specifically evaluating the effectiveness of these treatments in humans with mpox, animal studies have shown efficacy.

Special populations that might be considered for treatment include:

- Patients with severe disease (e.g., encephalitis, sepsis, or conditions requiring hospitalization).

- Individuals at increased risk of severe outcomes, such as those who are immunocompromised, pregnant or breastfeeding women, children, or those with complications.

- Patients with atypical mpox infections, particularly if the virus affects sensitive areas like the eyes, mouth, genitals, or anus, where infection could lead to more severe complications.43

Table 3. Treatment Options for mpox.

CMV = cytomegalovirus

Prevention

The CDC offers two orthopoxvirus vaccines, JYNNEOS and ACAM2000, to protect individuals at risk of mpox infection. Vaccination is recommended for those who have had known or suspected exposure to someone with mpox, engaged in sexual activity with a diagnosed individual in the past two weeks, or are planning travel to regions with a clade 1 mpox outbreak and anticipate sexual activity with new partners.49

The JYNNEOS vaccine is given as two subcutaneous injections, spaced 28 days apart, with peak immunity achieved 14 days after the second dose. It contains a live, non-replicating Vaccinia virus and is approved for preventing both smallpox and mpox in adults aged 18 years and older. No major contraindications have been identified other than a serious vaccine component allergy.50

The ACAM2000 vaccine uses a live, replication-competent Vaccinia virus, meaning it can produce additional viral particles after administration. Due to its replication capacity, it is contraindicated for individuals with moderate to severe immunosuppression, chronic skin conditions like eczema or other exfoliative disorders, and pregnant women. The vaccine is delivered as a single dose using a multiple-puncture technique with a bifurcated needle. The maximum immune response is typically reached 28 days post-vaccination.10, 50-51

Pearls and Pitfalls

- Although the majority of mpox cases have occurred in men who have sex with men (MSM), it is crucial to remain aware of other populations at risk.

- Avoid misdiagnosis due to similar rashes and use PCR testing for confirmatory testing.

- Be vigilant for complications such as encephalitis, proctitis, or secondary bacterial infections.

- Use caution when administering the ACAM2000 vaccine as it is contraindicated for individuals with immunosuppression, chronic skin conditions, or pregnancy.

References

- Karagoz A, Tombuloglu H, Alsaeed M, et al. Monkeypox (mpox) virus: Classification, origin, transmission, genome organization, antiviral drugs, and molecular diagnosis. J Infect Public Health. 2023;16(4):531-541. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2023.02.003

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO Director-General Declares Mpox Outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.who.int/news/item/14-08-2024-who-director-general-declares-mpox-outbreak-a-public-health-emergency-of-international-concern

- Rivers C, Watson C, Phelan AL. The Resurgence of Mpox in Africa. JAMA. 2024;332(13):1045. doi:10.1001/jama.2024.17829

- Stobbe M. US health officials report 1st case of new form of mpox in a traveler. The Associated Press. https://apnews.com/article/mpox-first-us-traveler-case-6e2ee003f53b7dc1d2e33ec16ba7c628. November 16, 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024.

- Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health Center for Health Security. Situation Update Mpox Virus: Clade I and Clade IIb.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://centerforhealthsecurity.org/sites/default/files/2024-06/20240610-mpoxsituationreport.pdf

- World Health Organization (WHO). Mpox (Monkeypox).; 2024. Accessed November 27, 2024. https://www.who.int/teams/blueprint/monkeypox#:~:text=Natural%20host%20of%20monkeypox%20virus,human%20primates%20and%20other%20species

- Acosta-España JD, Bonilla-Aldana DK, Luna C, Rodriguez-Morales AJ. The Resurgence of Mpox: A New Global Health Crisis. Infez Med. 2024;32(3). doi:10.53854/liim-3203-1

- Lu J, Xing H, Wang C, et al. Mpox (formerly monkeypox): pathogenesis, prevention and treatment. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2023;8(1):458. doi:10.1038/s41392-023-01675-2

- Liu H, Wang W, Zhang Y, et al. Global perspectives on smallpox vaccine against monkeypox: a comprehensive meta-analysis and systematic review of effectiveness, protection, safety and cross-immunogenicity. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2024;13(1):2387442. doi:10.1080/22221751.2024.2387442

- Long B, Koyfman A, Gottlieb M, et al. Monkeypox: A focused narrative review for emergency medicine clinicians. Am J Emerg Med. 2022;61:34-43. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2022.08.026

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Clinical Features of Mpox.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-signs/index.html

- Petersen E, Kantele A, Koopmans M, et al. Human Monkeypox. Infect Dis Clin North Am. 2019;33(4):1027-1043. doi:10.1016/j.idc.2019.03.001

- Feldmeyer L, Heidemeyer K, Yawalkar N. Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis: Pathogenesis, Genetic Background, Clinical Variants and Therapy. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17(8):1214. doi:10.3390/ijms17081214

- Robinson C, Jones J, Chachula L, Neiner J. Bullous Impetigo: A Mimicker of Immune-mediated Dermatoses. Mil Med. 2023;188(5-6):e1332-e1334. doi:10.1093/milmed/usab475

- Drolshagen H, Zoumberos N, Shalin S. Bullous Tinea: Single-Center Retrospective Histopathologic Review of 25 Skin Biopsies. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2023;147(11):1327-1332. doi:10.5858/arpa.2022-0243-OA

- Long B, Liang SY, Carius BM, et al. Mimics of Monkeypox: Considerations for the emergency medicine clinician. Am J Emerg Med. 2023;65:172-178. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2023.01.007

- Rao A, McCollum A. Smallpox & Other Orthopoxvirus-Associated Infections. In: CDC Yellowbook. ; 2022. Accessed November 27, 2024. https://wwwnc.cdc.gov/travel/yellowbook/2024/infections-diseases/smallpox-other-orthopoxvirus-associated-infections

- Doganay M, Metan G, Alp E. A review of cutaneous anthrax and its outcome. J Infect Public Health. 2010;3(3):98-105. doi:10.1016/j.jiph.2010.07.004

- Pattnaik H, Surani S, Goyal L, Kashyap R. Making Sense of Monkeypox: A Comparison of Other Poxviruses to the Monkeypox. Cureus. Published online April 24, 2023. doi:10.7759/cureus.38083

- Ortega-Loayza AG, Nguyen T. Cutaneous blastomycosis: a clue to a systemic disease. An Bras Dermatol. 2013;88(2):287-289. doi:10.1590/S0365-05962013000200022

- Garcia Garcia SC, Salas Alanis JC, Flores MG, Gonzalez Gonzalez SE, Vera Cabrera L, Ocampo Candiani J. Coccidioidomycosis and the skin: a comprehensive review. An Bras Dermatol. 2015;90(5):610-619. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20153805

- Hayashida MZ, Seque CA, Pasin VP, Enokihara MMSES, Porro AM. Disseminated cryptococcosis with skin lesions: report of a case series. An Bras Dermatol. 2017;92(5 suppl 1):69-72. doi:10.1590/abd1806-4841.20176343

- Farfán-Cano GG, Farfán-Cano SG, Farfán-Cano HR, Silva-Rojas GA, Solórzano-Bravo MT. Cutaneous histoplasmosis. A case report. Microbes Infect Chemother. 2022;2:e1353. doi:10.54034/mic.e1353

- Tang EC, Johnson KA, Alvarado L, et al. Characterizing the Rise of Disseminated Gonococcal Infections in California, July 2020–July 2021. Clin Infect Dis. 2023;76(2):194-200. doi:10.1093/cid/ciac805

- Liaw FY, Huang CF, Hsueh JT, Chiang CP. Eczema herpeticum: a medical emergency. Can Fam Physician Med Fam Can. 2012;58(12):1358-1361.

- Trayes K, Love G, Studdiford J. Erythema Multiforme: Recognition and Management. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(2). Accessed November 27, 2024. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/0715/p82.html

- Saguil A, Kane S, Lauters R, Mercado M. Hand-Foot-and-Mouth Disease: Rapid Evidence Review. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(7). Accessed November 27, 2024. https://aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2019/1001/p408.html

- Hübschen JM, Gouandjika-Vasilache I, Dina J. Measles. The Lancet. 2022;399(10325):678-690. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)02004-3

- Tsai J, Nagel MA, Gilden D. Skin rash in meningitis and meningoencephalitis. Neurology. 2013;80(19):1808-1811. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182918cda

- Hussain A, Kaler J, Lau G, Maxwell T. Clinical Conundrums: Differentiating Monkeypox From Similarly Presenting Infections. Cureus. Published online October 4, 2022. doi:10.7759/cureus.29929

- Tarbox M, Walker K, Tan M. Scabies. JAMA. 2018;320(6):612. doi:10.1001/jama.2018.7480

- Brazel M, Desai A, Are A, Motaparthi K. Staphylococcal Scalded Skin Syndrome and Bullous Impetigo. Med Kaunas Lith. 2021;57(11):1157. doi:10.3390/medicina57111157

- Joshi TP, Friske SK, Hsiou DA, Duvic M. New Practical Aspects of Sweet Syndrome. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2022;23(3):301-318. doi:10.1007/s40257-022-00673-4

- Atchade E, De Tymowski C, Grall N, Tanaka S, Montravers P. Toxic Shock Syndrome: A Literature Review. Antibiotics. 2024;13(1):96. doi:10.3390/antibiotics13010096

- World Health Organization (WHO). Laboratory Testing for the Monkeypox Virus: Interim Guidance, 23 May 2022.; 2022. Accessed November 26, 2024. WHO/MPX/laboratory/2022.1

- Bunse T, Ziel A, Hagen P, et al. Analytical and clinical evaluation of a novel real-time PCR-based detection kit for Mpox virus. Med Microbiol Immunol (Berl). 2024;213(1):18. doi:10.1007/s00430-024-00800-4

- Mills MG, Juergens KB, Gov JP, et al. Evaluation and clinical validation of monkeypox (mpox) virus real-time PCR assays. J Clin Virol. 2023;159:105373. doi:10.1016/j.jcv.2022.105373

- World Health Organization (WHO). WHO lists additional mpox diagnostic tests for emergency use.https://www.who.int/news/item/30-10-2024-who-lists-additional-mpox-diagnostic-tests-for-emergency-use. October 30, 2024. Accessed November 27, 2024.

- Zhou Y, Chen Z. Mpox: a review of laboratory detection techniques. Arch Virol. 2023;168(8):221. doi:10.1007/s00705-023-05848-w

- Kava CM, Rohraff DM, Wallace B, et al. Epidemiologic Features of the Monkeypox Outbreak and the Public Health Response — United States, May 17–October 6, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(45):1449-1456. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7145a4

- Curran KG, Eberly K, Russell OO, et al. HIV and Sexually Transmitted Infections Among Persons with Monkeypox — Eight U.S. Jurisdictions, May 17–July 22, 2022. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71(36):1141-1147. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm7136a1

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Mpox in Animals and Pets.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/about/mpox-in-animals-and-pets.html

- Shahid S. The American College of Emergency Physicians Guide to Monkeypox Disease.; 2022. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.acep.org/monkeypox-field-guide/cover-page

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Clinical Treatment of Mpox.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/hcp/clinical-care/index.html

- Micromedex. Tecovirimat. In: Merative US L.P.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian/CS/B803A2/ND_PR/evidencexpert/ND_P/evidencexpert/DUPLICATIONSHIELDSYNC/D6889E/ND_PG/evidencexpert/ND_B/evidencexpert/ND_AppProduct/evidencexpert/ND_T/evidencexpert/PFActionId/evidencexpert.GoToDashboard?docId=932503&contentSetId=100&title=Tecovirimat&servicesTitle=Tecovirimat&brandName=Tpoxx&UserMdxSearchTerm=TPOXX&=null#

- Micromedex. Cidofovir. In: Merative US L.P.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian/CS/573EC6/ND_PR/evidencexpert/ND_P/evidencexpert/DUPLICATIONSHIELDSYNC/135E16/ND_PG/evidencexpert/ND_B/evidencexpert/ND_AppProduct/evidencexpert/ND_T/evidencexpert/PFActionId/evidencexpert.DoIntegratedSearch?SearchTerm=Cidofovir%20&UserSearchTerm=Cidofovir%20&SearchFilter=filterNone&navitem=searchGlobal#

- Micromedex. Vaccinia Immune Globulin, Human. In: Merative US L.P.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian/CS/6B6750/ND_PR/evidencexpert/ND_P/evidencexpert/DUPLICATIONSHIELDSYNC/23F76E/ND_PG/evidencexpert/ND_B/evidencexpert/ND_AppProduct/evidencexpert/ND_T/evidencexpert/PFActionId/evidencexpert.IntermediateToDocumentLink?docId=2620&contentSetId=31&title=VACCINIA+IMMUNE+GLOBULIN%2C+HUMAN&servicesTitle=VACCINIA+IMMUNE+GLOBULIN%2C+HUMAN#

- Micromedex. Brincidofovir. In: Merative US L.P.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.micromedexsolutions.com/micromedex2/librarian/CS/A4F44E/ND_PR/evidencexpert/ND_P/evidencexpert/DUPLICATIONSHIELDSYNC/285910/ND_PG/evidencexpert/ND_B/evidencexpert/ND_AppProduct/evidencexpert/ND_T/evidencexpert/PFActionId/evidencexpert.DoIntegratedSearch?SearchTerm=Tembexa&UserSearchTerm=Tembexa&SearchFilter=filterNone&navitem=searchGlobal#

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U.S.). Mpox Vaccination.; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.cdc.gov/mpox/vaccines/index.html

- Poland GA, Kennedy RB, Tosh PK. Prevention of monkeypox with vaccines: a rapid review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2022;22(12):e349-e358. doi:10.1016/S1473-3099(22)00574-6

- Emergent Product Development Gaithersburg Inc. ACAM2000® [Smallpox and Mpox (Vaccinia) Vaccine, Live].; 2024. Accessed November 26, 2024. https://www.fda.gov/media/75792/download