Authors: Nikhil B. Bhana, MD (EM Resident Physician, University of Massachusetts/UMass Chan Medical School); Clarence Kong, MD (Pain Fellow, Eastern Virginia Medical School – Virginia Health Sciences at Old Dominion University); Mani Hashemi, MD (EM Attending, HCA Florida Mercy Hospital); S.M. Jafar Mahmood, MD (Pain Medicine Attending, Paincare Medical Practice) // Reviewed by: Jessica Pelletier, DO, MHPE (EM Attending, APD, University of Missouri-Columbia), Marina Boushra, MD (EM-CCM Attending, Cleveland Clinic); Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Introduction:

- Pain management in the ED can be a unique challenge.

- Most patients presenting to the ED seek care for pain-related complaints.1

- The ED is a fast-paced environment where patient stability and life-and-limb-threatening conditions are prioritized.

- The American Academy of Emergency Medicine has called effective, efficient, and safe pain management a “specialty-defining skill.”2

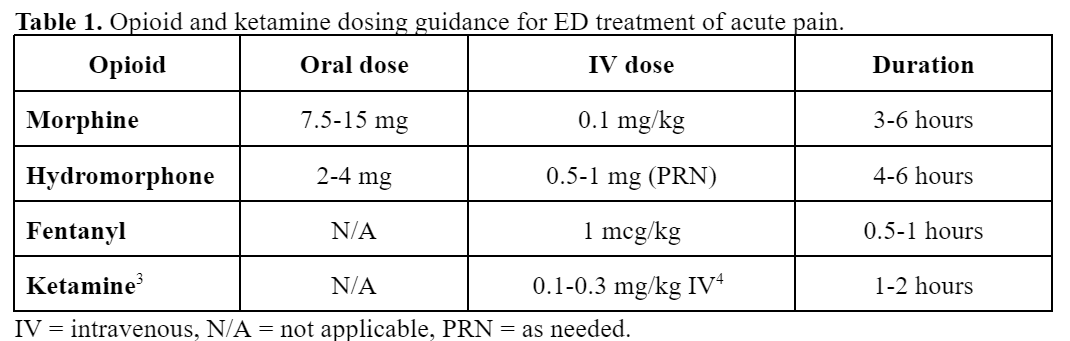

- This post discusses stepwise management of the most common painful ED diagnosis, organized by anatomical location. Medication dosages detailed in this article are suggestions; local institutional pharmacy dosage policies should be followed.

Cases:

- A 28-year-old female presents to the ED with sharp, left-sided chest pain that started two days ago. The pain is worse with deep breaths, coughing, or certain movements, and improves with rest and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs).

- A 45-year-old male presents to the ED after a motor vehicle collision where he was the restrained driver. He reports severe, localized chest pain, worsened by breathing, coughing, and movement. He denies shortness of breath or abdominal pain but has difficulty taking deep breaths due to pain.

- A 32-year-old male presents to the ED with a sharp, central chest pain that has been worsening over the past 3 days. The pain is relieved by sitting forward and worsens when lying flat or taking deep breaths. He reports a recent upper respiratory infection but denies shortness of breath, leg swelling, or recent trauma.

Chest Pain:

- Within the United States, chest pain accounted for nearly 7.6 million patient complaints in 2017, making it the second most common ED complaint.5

- In addition to the management of acute pain, it is important to identify if the cause of chest pain is life-threatening (Table 2).

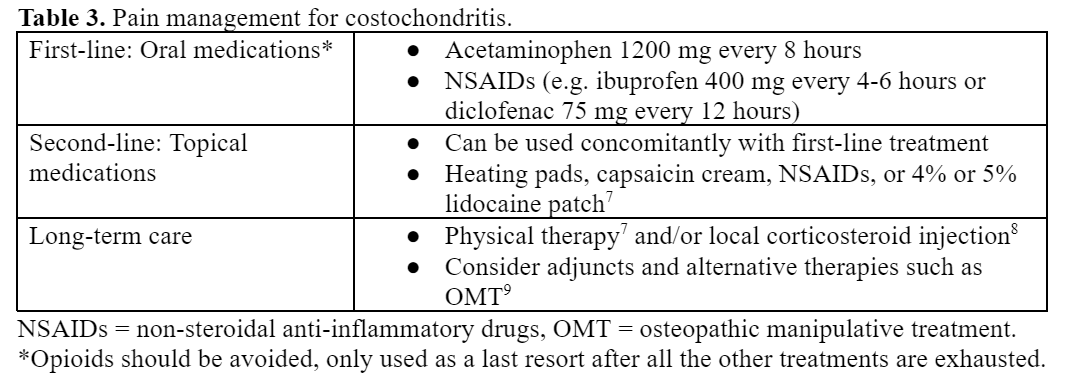

- Costochondritis, rib fractures, and pericarditis are common causes of chest pain that can be treated with multimodal regimens.

Costochondritis:

- Costochondritis is inflammation of the sternal articulations and costal cartilages causing chest wall pain that is usually reproducible with palpation.6

- Clinical course can last weeks to months.

- Most cases abate by one year. The provider must educate the patient on the anticipated clinical course.7

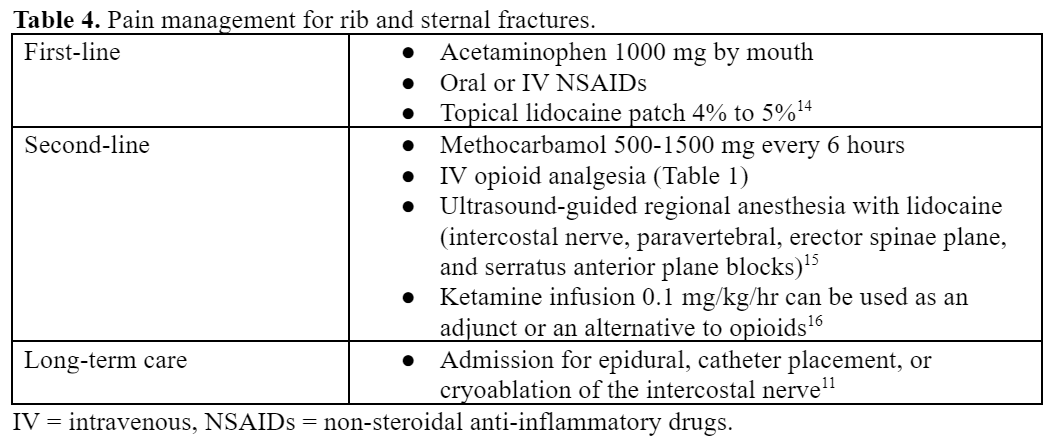

Rib and Sternal Fractures:

- Rib fractures are often caused by blunt chest trauma.

- Up to two-thirds of rib fractures are missed on initial chest radiographs.10

- Rib fractures can result in exquisite pain and can cause complications like pneumothorax, pneumonia, atelectasis, and delirium.11

- Aggressive and timely analgesia is critical to reduce subsequent complications, morbidity, and mortality.12,13

Pericarditis:

- Pericarditis, inflammation of the pericardium, is known to cause pleuritic chest pain.

- Pain can be associated with a friction rub on cardiac auscultation, a pericardial effusion on a bedside echocardiogram, or diffuse ST elevations on an EKG.17

Cases:

- A 26-year-old female presents to the ED with a throbbing, unilateral headache on the right side that began 12 hours ago. The pain is moderate to severe in intensity, associated with nausea, photophobia, and phonophobia. She reports a history of similar headaches but this one is more prolonged. She denies any recent head trauma, neck stiffness, or vision changes.

- A 34-year-old male presents to the ED with severe, excruciating pain around his left eye. The pain began abruptly 1 hour ago, described as a stabbing sensation, and has occurred daily at the same time for the past week, each episode lasting about 45 minutes. He also reports associated left-sided nasal congestion, tearing, and ptosis during the attacks. He denies any nausea, photophobia, or aura.

- A 30-year-old female presents to the ED with a dull, bilateral headache that started 3 days ago. She describes the pain as a tight, band-like pressure around her forehead and temples. The headache is mild to moderate in intensity, without associated nausea, vomiting, photophobia, or phonophobia. She reports increased stress at work but denies any recent trauma or history of migraines.

Headache:

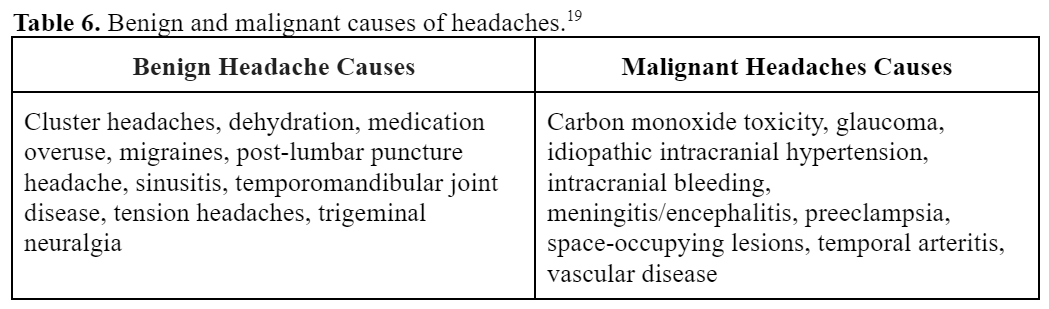

- Headaches account for over 2.1 million ED visits per year (2.2% of visits) and represent the 4th most common chief concern in the ED.19

- A variety of etiologies can lead to a patient presenting to the ED with headache. These causes can be divided into two distinct categories: benign and malignant.

- Red-flag headache characteristics can point to malignant pathology that should warrant further workup (Table 6).

- Headache red-flag characteristics include neurological symptoms, thunderclap nature, syncope, trauma, immunocompromised, coagulopathy, fever, rash, seizure, nuchal rigidity, altered mental status, pregnancy, temporal tenderness, jaw claudication, and cancer history.

- This post focuses on pain management for benign headaches.

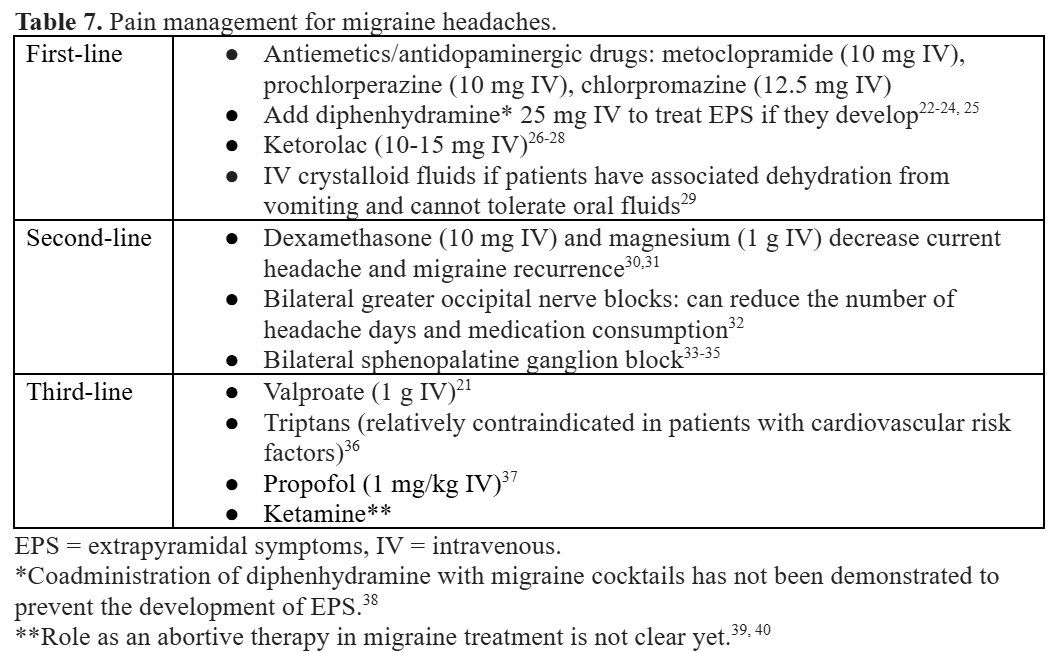

Migraines:

- Migraines cause approximately 1.2 million visits to the ED in the United States (US).20

- Migraines are defined as recurrent headaches lasting 4-72 hours and are often characterized by unilateral, pulsating, moderate to severe pain that is aggravated by physical activity.

- Frequently associated symptoms include photophobia, phonophobia, nausea, or vomiting.21

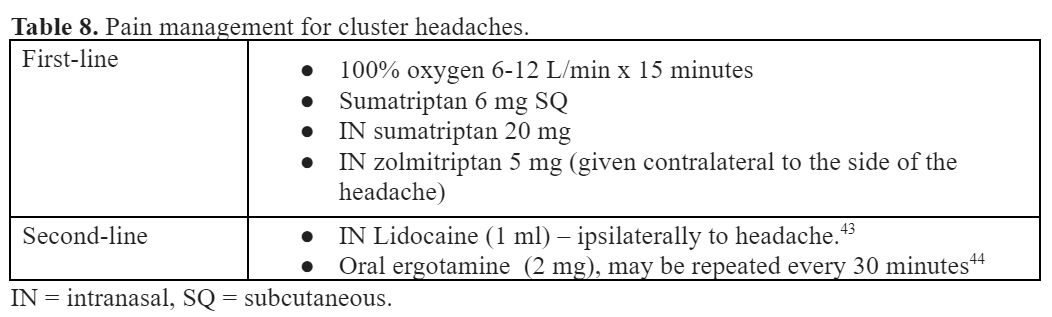

Cluster Headaches:

- Cluster headaches are a primary headache disorder affecting up to 0.1% of the population.

- These headaches occur in “clusters” over days to weeks, at the same time of day, and in the same anatomical location.41

- Clutter headaches are characterized by severe and unilateral orbital, supraorbital, or temporal pain lasting 15–180 minutes. The headache is usually accompanied by at least one of the following: ipsilateral conjunctival injection, lacrimation, congestion, eyelid edema, facial diaphoresis, miosis, ptosis, restlessness, or agitation. Attacks have a frequency from every other day to eight per day.19

- Effective treatment includes avoidance of triggers, abortive strategies, and prophylactic medication.

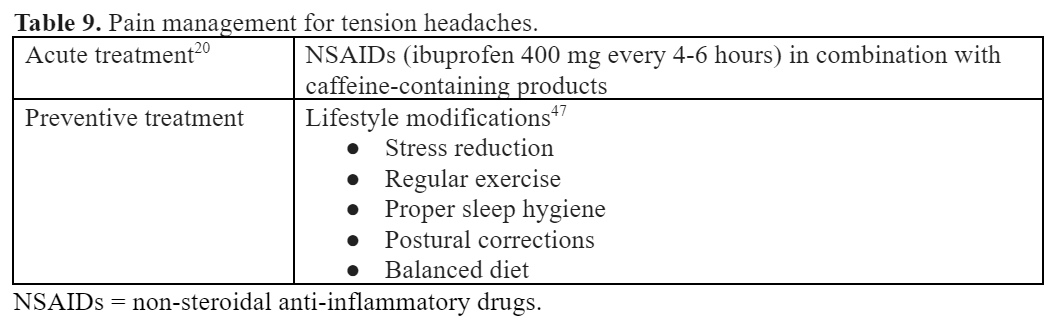

Tension Headache:

- A primary headache disorder that presents with bilateral non-pulsating pain in a band-like or vice-like distribution around the head. Tension headaches are characterized by bilateral location and mild to moderate intensity.

- Nausea, vomiting, photophobia, and phonophobia are NOT associated with tension headaches.21

Case:

- A 40-year-old male presents to the ED with a burning epigastric pain that has been worsening over the past week. The pain is worse after meals and at night, but improves with antacids. He reports associated bloating and frequent burping but denies nausea, vomiting, or weight loss. He has a history of occasional NSAID use for joint pain.

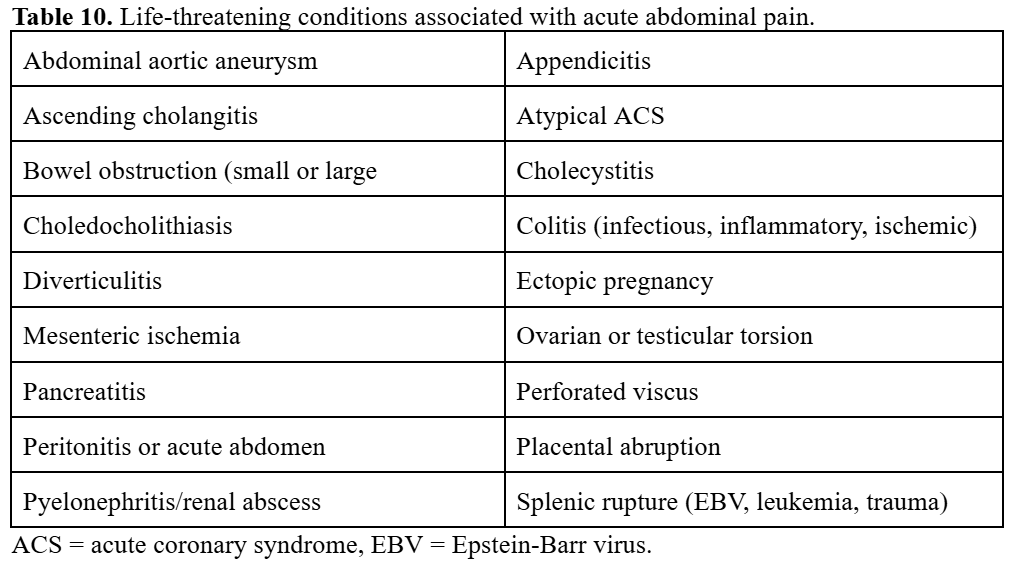

Abdominal Pain:

- Acute abdominal pain accounts for approximately 7 million ED visits annually (5 to 10% of all ED visits).48,49

- The abdominal region contains a multitude of critical organs including the liver, spleen, kidneys, pancreas, gallbladder, stomach, bowel, aorta, inferior vena cava, and ovaries. Chest and thoracic pain commonly refer to the abdominal region.50

- The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain is broad and diagnoses can be easily missed. In up to 25% of cases, the exact etiology of abdominal pain remains undifferentiated at the time of discharge.51

Abdominal Pain Clinical Pearls:

- Patients over 65 have a six- to eight-fold increased risk of mortality compared to younger patients when presenting to the ED for abdominal pain.52,53 Their pain intensity does not correlate with disease severity and pain location does not correlate with disease location. A low threshold to obtain imaging should be maintained in this population.

- Every patient, assigned female-at-birth (AFAB), of child-bearing age should get a pregnancy test.

- Physicians should ensure the patient can tolerate oral intake before discharge.

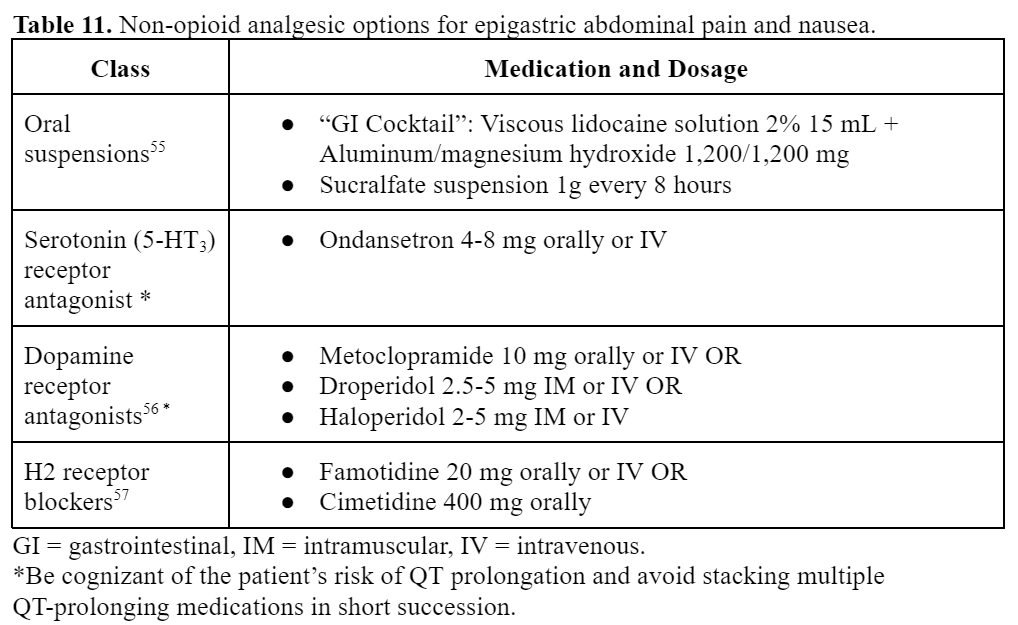

- Treatment pathways for various causes of abdominal pain are similar. Generally, a stepwise approach should be utilized.

- Both pain and associated nausea should be treated.

- Abdominal pain and gastritis caused by NSAIDs, alcohol, or marijuana may benefit from cessation of the inciting substance.

Mild to Moderate Gastric Pain:

- Common etiologies include gastritis, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), and other gastric pain.

- Pain can be gnawing, aching, burning, and located in the upper abdomen.

- Pain can be improved or exacerbated with meals.54

- It is vital to consider dangerous epigastric pain mimickers like acute coronary syndrome (ACS), hepatobiliary disease, or pancreatitis.52

Moderate to Severe Abdominal Pain:

- Analgesia has been proven to not interfere with abdominal pain assessment or diagnosis.53,60

- Moderate to severe abdominal pain should be treated aggressively while the etiology of pain is investigated with labs or imaging.

- Opioid analgesia is appropriate for moderate to severe acute abdominal pain (Table 1).

- The goal of pain management is not to eliminate pain, but rather to facilitate examination and workup.

Case:

- A 50-year-old male presents to the ED with lower back pain that began after lifting a heavy object 3 days ago. The pain is dull, localized to the lumbar region, and worsens with movement or prolonged sitting. He denies radiating pain, numbness, weakness, or bowel/bladder dysfunction. He has no history of trauma or previous back problems.

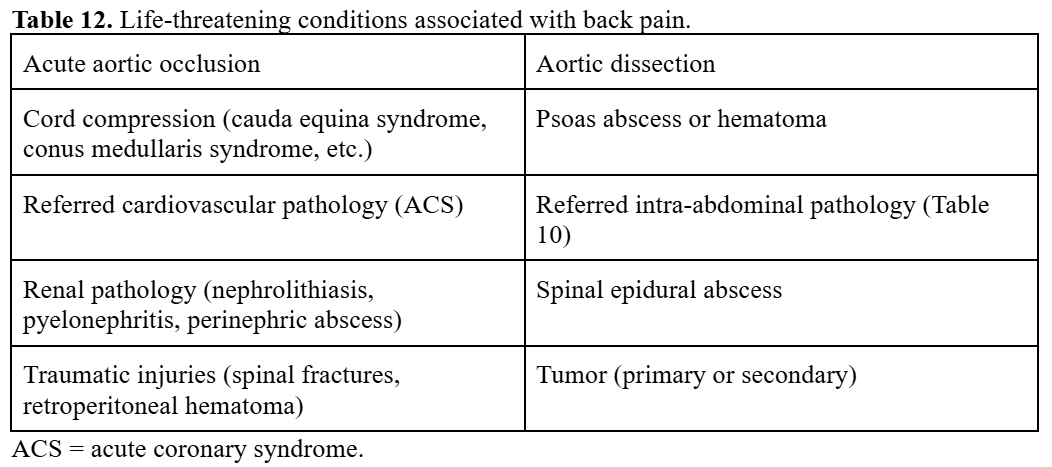

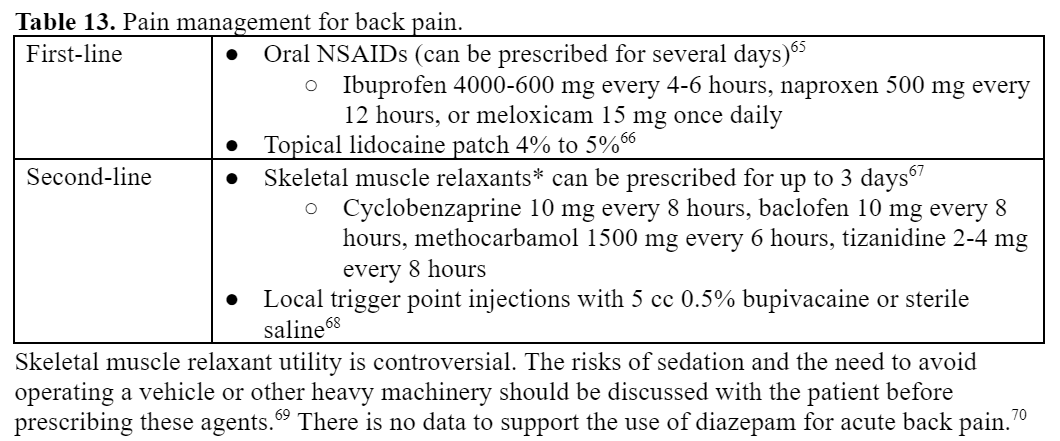

Back Pain:

- Back pain is the eighth most common concern in the ED in the US.5

- The etiology of acute back pain is often multifactorial. Even after standard pain management, up to one-third of patients will continue to have pain for months.61

- It is critical to educate patients on outpatient nonpharmacologic treatments as most back pain improves regardless of the pharmacologic treatment used.62,63

- The most recent American College of Physicians Guidelines recommend the following:64

- For acute and subacute low back pain: heat (moderate-quality evidence); and acupuncture, massage, or spinal manipulation (low-quality evidence).

- For chronic low back pain: acupuncture, exercise, mindfulness-based stress reduction, multidisciplinary rehabilitation (moderate-quality evidence); and cognitive behavioral therapy, electromyography biofeedback, low-level laser therapy, motor control exercise, operant therapy, progressive relaxation, spinal manipulation, tai chi, or yoga (low-quality evidence).

- Pharmacologic therapy should only be utilized for chronic low back pain for patients who have not responded adequately to the aforementioned options.

- The most recent American College of Physicians Guidelines recommend the following:64

- Managing patient expectations is vital. Patients must understand the likelihood of persistent pain during recovery.

Case:

- A 35-year-old female presents to the clinic with diffuse muscle aches and joint stiffness, primarily in the shoulders and lower back, that began 1 week ago after starting a new exercise routine. The pain is worse with activity but improves with rest. She denies any trauma, swelling, or redness in the joints, as well as fever or weight loss.

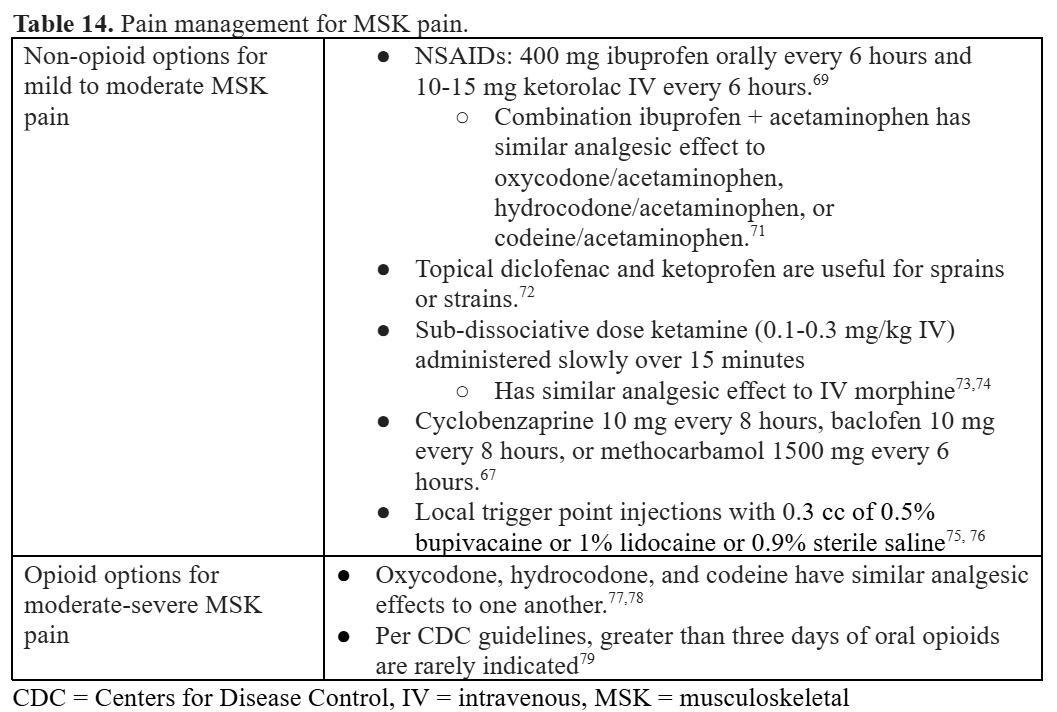

Musculoskeletal Pain:

- Musculoskeletal (MSK) pain is a common painful complaint seen in the ED.5

- Etiologies range from long bone fractures, chest pain, back pain, and soft tissue contusions.

- The diversity of MSK pain etiologies necessitates a multimodal approach of opioid, non-opioid, and regional analgesics.

Case:

- A 60-year-old male with a history of diabetes presents to the clinic with burning and tingling pain in both feet, which has been progressively worsening over the past several months. The pain is described as a constant, sharp, “pins-and-needles” sensation, particularly at night, affecting his sleep. He denies any recent trauma, weakness, or changes in balance but reports some numbness in his toes.

Neuropathic Pain:

- Neuropathic pain is triggered by lesions to the somatosensory nervous system that alter its structure and function.

- Pain can be triggered spontaneously and noxious/innocuous stimuli are pathologically amplified.80

- It can be caused by traumatic nerve, spinal cord, or brain injury (including stroke) or can be a sequela of conditions like diabetes, HIV/AIDS, postherpetic neuropathies, multiple sclerosis, cancer, or chemotherapies.81

Other Common Causes of Pain:

Cases:

- 22-year-old female with a known history of sickle cell disease (SCD) presents to the ED with severe, sharp pain in her chest and back that began suddenly 4 hours ago. She rates the pain as 9/10 and describes it as the worst pain she has ever experienced. She reports feeling fatigued and has had mild fever and chills over the past day.

- A 28-year-old male presents to the ED with sudden onset, severe right flank pain that began 2 hours ago. He describes the pain as sharp and intermittent, radiating to the groin. He reports associated nausea but denies vomiting, fever, or changes in urinary habits.

Sickle Cell Disease (SCD):

- Vaso-occlusive pain crises are the most common reason for patients with SCD to present to the ED.84

- It is critical to identify life-threatening conditions associated with pain crises (Table 16).

- Sickle cell pain management has been shown to reduce hospital admissions.85

- In addition to pain management, adequate hydration and oxygenation are key to managing a vaso-occlusive pain crisis.86

- Clinicians should strongly consider providing SCD patients with incentive spirometers when treating them for pain crises, as this simple and inexpensive intervention can help reduce the risk for acute chest syndrome.87

- Following the patient’s individualized care plan (where available) is essential.

Renal Colic Pain:

- Renal colic pain constitutes approximately 2 million annual ED visits and approximately 1 in 10 people experience this condition.90

- Renal colic pain is painful and prompt pain management can reduce associated nausea and vomiting.

- Pain is hypothesized to be prostaglandin-mediated and thus NSAIDs are the mainstay treatment.91

Pearls and Pitfalls:

- Management of pain in the ED begins with a thorough assessment to rule out life-threatening conditions.

- Identifying the specific type of pain is crucial, allowing for targeted treatments.

- A comprehensive, patient-centered approach to pain management ensures effective treatment across these diverse pain syndromes, ultimately improving patient outcomes.

References:

- Chang HY, Daubresse M, Kruszewski SP, Alexander GC. Prevalence and treatment of pain in EDs in the United States, 2000 to 2010. Am J Emerg Med. May 2014;32(5):421-31. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2014.01.015

- Motov S, Strayer R, Hayes BD, et al. The Treatment of Acute Pain in the Emergency Department: A White Paper Position Statement Prepared for the American Academy of Emergency Medicine. J Emerg Med. 05 2018;54(5):731-736. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2018.01.020

- Motov S, Rockoff B, Cohen V, et al. Intravenous Subdissociative-Dose Ketamine Versus Morphine for Analgesia in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Ann Emerg Med. Sep 2015;66(3):222-229.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2015.03.004

- Balzer N, McLeod SL, Walsh C, Grewal K. Low-dose Ketamine For Acute Pain Control in the Emergency Department: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. Acad Emerg Med. 2021 Apr;28(4):444-454. doi: 10.1111/acem.14159. Epub 2021 Jan 2. PMID: 33098707.

- National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NHAMCS) 2017 Emergency Department Summary Tables (2017).

- Fam AG, Smythe HA. Musculoskeletal chest wall pain. CMAJ. Sep 01 1985;133(5):379-89.

- Spalding L, Reay E, Kelly C. Cause and outcome of atypical chest pain in patients admitted to hospital. J R Soc Med. Mar 2003;96(3):122-5. doi:10.1258/jrsm.96.3.122

- Freeston J, Karim Z, Lindsay K, Gough A. Can early diagnosis and management of costochondritis reduce acute chest pain admissions? J Rheumatol. Nov 2004;31(11):2269-71.

- Koch J, Tsui C, Talsma J, Pierce-Talsma S. Osteopathic Manipulative Treatment for Inhaled Rib Somatic Dysfunction. Journal of Osteopathic Medicine. 2020;120(10):696-697. doi:10.7556/jaoa.2020.109

- Turk F, Kurt AB, Saglam S. Evaluation by ultrasound of traumatic rib fractures missed by radiography. Emerg Radiol. Nov 2010;17(6):473-7. doi:10.1007/s10140-010-0892-9

- Ho AM, Karmakar MK, Critchley LA. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured ribs: a focus on regional techniques. Curr Opin Crit Care. Aug 2011;17(4):323-7. doi:10.1097/MCC.0b013e328348bf6f

- Murphy CE, Raja AS, Baumann BM, et al. Rib Fracture Diagnosis in the Panscan Era. Ann Emerg Med. Dec 2017;70(6):904-909. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2017.04.011

- Witt CE, Bulger EM. Comprehensive approach to the management of the patient with multiple rib fractures: a review and introduction of a bundled rib fracture management protocol. Trauma Surg Acute Care Open. 2017;2(1):e000064. doi:10.1136/tsaco-2016-000064

- Zink KA, Mayberry JC, Peck EG, Schreiber MA. Lidocaine patches reduce pain in trauma patients with rib fractures. Am Surg. Apr 2011;77(4):438-42. doi:10.1177/000313481107700419

- Karmakar MK, Ho AM. Acute pain management of patients with multiple fractured ribs. J Trauma. Mar 2003;54(3):615-25. doi:10.1097/01.TA.0000053197.40145.62

- Puri L, Morgan KJ, Anghelescu DL. Ketamine and lidocaine infusions decrease opioid consumption during vaso-occlusive crisis in adolescents with sickle cell disease. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 12 2019;13(4):402-407. doi:10.1097/SPC.0000000000000437

- Imazio M, Gaita F. Diagnosis and treatment of pericarditis. Heart. Jul 2015;101(14):1159-68. doi:10.1136/heartjnl-2014-306362

- LeWinter MM. Clinical practice. Acute pericarditis. N Engl J Med. Dec 18 2014;371(25):2410-6. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1404070

- Goldstein JN, Camargo CA, Pelletier AJ, Edlow JA. Headache in United States emergency departments: demographics, work-up and frequency of pathological diagnoses. Cephalalgia. Jun 2006;26(6):684-90. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01093.x

- Friedman BW, West J, Vinson DR, Minen MT, Restivo A, Gallagher EJ. Current management of migraine in US emergency departments: an analysis of the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Cephalalgia. Apr 2015;35(4):301-9. doi:10.1177/0333102414539055

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS) The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition. Cephalalgia. 01 2018;38(1):1-211. doi:10.1177/0333102417738202

- Friedman BW, Garber L, Yoon A, et al. Randomized trial of IV valproate vs metoclopramide vs ketorolac for acute migraine. Neurology. Mar 18 2014;82(11):976-83. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000223

- Gaffigan ME, Bruner DI, Wason C, Pritchard A, Frumkin K. A Randomized Controlled Trial of Intravenous Haloperidol vs. Intravenous Metoclopramide for Acute Migraine Therapy in the Emergency Department. J Emerg Med. Sep 2015;49(3):326-34. doi:10.1016/j.jemermed.2015.03.023

- D’Souza RS, Mercogliano C, Ojukwu E, et al. Effects of prophylactic anticholinergic medications to decrease extrapyramidal side effects in patients taking acute antiemetic drugs: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Emerg Med J. May 2018;35(5):325-331. doi:10.1136/emermed-2017-206944

- Mokhtari A, Yip O, Alain J, Berthelot S. Prophylactic Administration of Diphenhydramine to Reduce Neuroleptic Side Effects in the Acute Care Setting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;60(2):165-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.09.031. Epub 2020 Oct 31. PMID: 33131965.

- Taggart E, Doran S, Kokotillo A, Campbell S, Villa-Roel C, Rowe BH. Ketorolac in the treatment of acute migraine: a systematic review. Headache. Feb 2013;53(2):277-87. doi:10.1111/head.12009

- Rao AS, Gelaye B, Kurth T, Dash PD, Nitchie H, Peterlin BL. A Randomized Trial of Ketorolac vs. Sumatripan vs. Placebo Nasal Spray (KSPN) for Acute Migraine. Headache. Feb 2016;56(2):331-40. doi:10.1111/head.12767

- Forestell B, Sabbineni M, Sharif S, Chao J, Eltorki M. Comparative Effectiveness of Ketorolac Dosing Strategies for Emergency Department Patients With Acute Pain. Ann Emerg Med. 2023 Nov;82(5):615-623. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2023.04.011. Epub 2023 May 13. PMID: 37178102.

- Jones CW, Gaughan JP, McLean SA. Epidemiology of intravenous fluid use for headache treatment: Findings from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Am J Emerg Med. May 2017;35(5):778-781. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.01.030

- Latev A, Friedman BW, Irizarry E, et al. A Randomized Trial of a Long-Acting Depot Corticosteroid Versus Dexamethasone to Prevent Headache Recurrence Among Patients With Acute Migraine Who Are Discharged From an Emergency Department. Ann Emerg Med. 02 2019;73(2):141-149. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.09.028

- Delavar Kasmaei H, Amiri M, Negida A, Hajimollarabi S, Mahdavi N. Ketorolac versus Magnesium Sulfate in Migraine Headache Pain Management; a Preliminary Study. Emerg (Tehran). 2017;5(1):e2.

- Inan LE, Inan N, Karadaş Ö, et al. Greater occipital nerve blockade for the treatment of chronic migraine: a randomized, multicenter, double-blind, and placebo-controlled study. Acta Neurol Scand. Oct 2015;132(4):270-7. doi:10.1111/ane.12393

- Cady R, Saper J, Dexter K, Manley HR. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of repetitive transnasal sphenopalatine ganglion blockade with tx360(®) as acute treatment for chronic migraine. Headache. Jan 2015;55(1):101-16. doi:10.1111/head.12458

- Schaffer JT, Hunter BR, Ball KM, Weaver CS. Noninvasive sphenopalatine ganglion block for acute headache in the emergency department: a randomized placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. May 2015;65(5):503-10. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.12.012

- Khan S, Schoenen J, Ashina M. Sphenopalatine ganglion neuromodulation in migraine: what is the rationale? Cephalalgia. Apr 2014;34(5):382-91. doi:10.1177/0333102413512032

- Akpunonu BE, Mutgi AB, Federman DJ, et al. Subcutaneous sumatriptan for treatment of acute migraine in patients admitted to the emergency department: a multicenter study. Ann Emerg Med. Apr 1995;25(4):464-9. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70259-8

- Goldstein JN, Camargo CA Jr, Pelletier AJ, Edlow JA. Headache in United States emergency departments: demographics, work-up and frequency of pathological diagnoses. Cephalalgia. 2006 Jun;26(6):684-90. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2982.2006.01093.x. PMID: 16686907.

- Mokhtari A, Yip O, Alain J, Berthelot S. Prophylactic Administration of Diphenhydramine to Reduce Neuroleptic Side Effects in the Acute Care Setting: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. J Emerg Med. 2021 Feb;60(2):165-174. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2020.09.031. Epub 2020 Oct 31. PMID: 33131965.

- Bilhimer MH, Groth ME, Holmes AK. Ketamine for Migraine in the Emergency Department. Adv Emerg Nurs J. 2020 Apr/Jun;42(2):96-102. doi: 10.1097/TME.0000000000000296. PMID: 32358422.

- Etchison AR, Bos L, Ray M, McAllister KB, Mohammed M, Park B, Phan AV, Heitz C. Low-dose Ketamine Does Not Improve Migraine in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Placebo-controlled Trial. West J Emerg Med. 2018 Nov;19(6):952-960. doi: 10.5811/westjem.2018.8.37875. Epub 2018 Sep 10. PMID: 30429927; PMCID: PMC6225951.

- Wei DY, Yuan Ong JJ, Goadsby PJ. Cluster Headache: Epidemiology, Pathophysiology, Clinical Features, and Diagnosis. Ann Indian Acad Neurol. Apr 2018;21(Suppl 1):S3-S8. doi:10.4103/aian.AIAN_349_17

- Mir P, Alberca R, Navarro A, et al. Prophylactic treatment of episodic cluster headache with intravenous bolus of methylprednisolone. Neurol Sci. Dec 2003;24(5):318-21. doi:10.1007/s10072-003-0182-3

- Robbins L. Intranasal lidocaine for cluster headache. Headache. Feb 1995;35(2):83-4. doi:10.1111/j.1526-4610.1995.hed3502083.x

- May A, Leone M, Afra J, et al. EFNS guidelines on the treatment of cluster headache and other trigeminal-autonomic cephalalgias. Eur J Neurol. Oct 2006;13(10):1066-77. doi:10.1111/j.1468-1331.2006.01566.x

- Francis GJ, Becker WJ, Pringsheim TM. Acute and preventive pharmacologic treatment of cluster headache. Neurology. Aug 03 2010;75(5):463-73. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181eb58c8

- Dodick DW, Goadsby PJ, Lucas C, et al. Phase 3 randomized, placebo-controlled study of galcanezumab in patients with chronic cluster headache: Results from 3-month double-blind treatment. Cephalalgia. 08 2020;40(9):935-948. doi:10.1177/0333102420905321

- Kaniecki RG. Tension-type headache. Continuum (Minneap Minn). Aug 2012;18(4):823-34. doi:10.1212/01.CON.0000418645.32032.32

- Kamin RA, Nowicki TA, Courtney DS, Powers RD. Pearls and pitfalls in the emergency department evaluation of abdominal pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. Feb 2003;21(1):61-72, vi. doi:10.1016/s0733-8627(02)00080-9

- Brewer BJ, Golden GT, Hitch DC, Rudolf LE, Wangensteen SL. Abdominal pain. An analysis of 1,000 consecutive cases in a University Hospital emergency room. Am J Surg. Feb 1976;131(2):219-23. doi:10.1016/0002-9610(76)90101-x

- Hwang SY, Park EH, Shin ES, Jeong MH. Comparison of factors associated with atypical symptoms in younger and older patients with acute coronary syndromes. J Korean Med Sci. Oct 2009;24(5):789-94. doi:10.3346/jkms.2009.24.5.789

- Powers RD, Guertler AT. Abdominal pain in the ED: stability and change over 20 years. Am J Emerg Med. May 1995;13(3):301-3. doi:10.1016/0735-6757(95)90204-X

- Hustey FM, Meldon SW, Banet GA, Gerson LW, Blanda M, Lewis LM. The use of abdominal computed tomography in older ED patients with acute abdominal pain. Am J Emerg Med. May 2005;23(3):259-65. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2005.02.021

- Lewis LM, Banet GA, Blanda M, Hustey FM, Meldon SW, Gerson LW. Etiology and clinical course of abdominal pain in senior patients: a prospective, multicenter study. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. Aug 2005;60(8):1071-6. doi:10.1093/gerona/60.8.1071

- Robinson P, Perkins JC. Approach to Patients with Epigastric Pain. Emerg Med Clin North Am. May 2016;34(2):191-210. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2015.12.012

- Wrenn K, Slovis CM, Gongaware J. Using the “GI cocktail”: a descriptive study. Ann Emerg Med. Dec 1995;26(6):687-90. doi:10.1016/s0196-0644(95)70038-2

- Cowling M, Covington S, Roehmer C, Musey P. Characterizing the role of haloperidol for analgesia in the Emergency Department. J Pain Manag. 2019;12(2):141-146.

- Friesen CA, Schurman JV, Colombo JM, Abdel-Rahman SM. Eosinophils and mast cells as therapeutic targets in pediatric functional dyspepsia. World J Gastrointest Pharmacol Ther. Nov 06 2013;4(4):86-96. doi:10.4292/wjgpt.v4.i4.86

- Sakurai K, Nagahara A, Inoue K, et al. Efficacy of omeprazole, famotidine, mosapride and teprenone in patients with upper gastrointestinal symptoms: an omeprazole-controlled randomized study (J-FOCUS). BMC Gastroenterol. May 01 2012;12:42. doi:10.1186/1471-230X-12-42

- Thomas SH, Silen W, Cheema F, et al. Effects of morphine analgesia on diagnostic accuracy in Emergency Department patients with abdominal pain: a prospective, randomized trial. J Am Coll Surg. Jan 2003;196(1):18-31. doi:10.1016/s1072-7515(02)01480-1

- Ranji SR, Goldman LE, Simel DL, Shojania KG. Do opiates affect the clinical evaluation of patients with acute abdominal pain? JAMA. Oct 11 2006;296(14):1764-74. doi:10.1001/jama.296.14.1764

- Friedman BW, Conway J, Campbell C, Bijur PE, John Gallagher E. Pain One Week After an Emergency Department Visit for Acute Low Back Pain Is Associated With Poor Three-month Outcomes. Acad Emerg Med. 10 2018;25(10):1138-1145. doi:10.1111/acem.13453

- Byström MG, Rasmussen-Barr E, Grooten WJ. Motor control exercises reduces pain and disability in chronic and recurrent low back pain: a meta-analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Mar 15 2013;38(6):E350-8. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31828435fb

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, et al. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 04 04 2017;166(7):514-530. doi:10.7326/M16-2367

- Qaseem A, Wilt TJ, McLean RM, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians; Denberg TD, Barry MJ, Boyd C, Chow RD, Fitterman N, Harris RP, Humphrey LL, Vijan S. Noninvasive Treatments for Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Low Back Pain: A Clinical Practice Guideline From the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017 Apr 4;166(7):514-530. doi: 10.7326/M16-2367. Epub 2017 Feb 14. PMID: 28192789.

- Roelofs PD, Deyo RA, Koes BW, Scholten RJ, van Tulder MW. Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. Jan 23 2008;(1):CD000396. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000396.pub3

- Gimbel J, Linn R, Hale M, Nicholson B. Lidocaine patch treatment in patients with low back pain: results of an open-label, nonrandomized pilot study. Am J Ther. 2005 Jul-Aug 2005;12(4):311-9. doi:10.1097/01.mjt.0000164828.57392.ba

- van Tulder MW, Touray T, Furlan AD, Solway S, Bouter LM, Group CBR. Muscle relaxants for nonspecific low back pain: a systematic review within the framework of the cochrane collaboration. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Sep 01 2003;28(17):1978-92. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000090503.38830.AD

- Garvey TA, Marks MR, Wiesel SW. A prospective, randomized, double-blind evaluation of trigger-point injection therapy for low-back pain. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). Sep 1989;14(9):962-4. doi:10.1097/00007632-198909000-00008

- Werthman AM, Jolley BD, Rivera A, Rusli MA. Emergency Department Management of Low Back Pain: A Comparative Review of Guidelines and Practices. Cureus. 2024 Feb 6;16(2):e53712. doi: 10.7759/cureus.53712. PMID: 38455774; PMCID: PMC10919314.

- Friedman BW, Irizarry E, Solorzano C, et al. Diazepam Is No Better Than Placebo When Added to Naproxen for Acute Low Back Pain. Ann Emerg Med. Aug 2017;70(2):169-176.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2016.10.002

- Seymour RA, Ward-Booth P, Kelly PJ. Evaluation of different doses of soluble ibuprofen and ibuprofen tablets in postoperative dental pain. Br J Oral Maxillofac Surg. Feb 1996;34(1):110-4. doi:10.1016/s0266-4356(96)90147-3

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Esses D, Barnaby DP, Baer J. Effect of a Single Dose of Oral Opioid and Nonopioid Analgesics on Acute Extremity Pain in the Emergency Department: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA. 11 07 2017;318(17):1661-1667. doi:10.1001/jama.2017.16190

- Derry S, Wiffen PJ, Kalso EA, et al. Topical analgesics for acute and chronic pain in adults – an overview of Cochrane Reviews. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 05 12 2017;5:CD008609. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008609.pub2

- Kirschner JM, Hunter BR. Is Low-Dose Ketamine an Effective Alternative to Opioids for Acute Pain? Ann Emerg Med. May 2019;73(5):e47-e49. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2018.11.001

- Motov S, Mai M, Pushkar I, et al. A prospective randomized, double-dummy trial comparing IV push low dose ketamine to short infusion of low dose ketamine for treatment of pain in the ED. Am J Emerg Med. Aug 2017;35(8):1095-1100. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.03.004

- Tschopp KP, Gysin C. Local injection therapy in 107 patients with myofascial pain syndrome of the head and neck. ORL J Otorhinolaryngol Relat Spec. 1996 Nov-Dec;58(6):306-10. doi: 10.1159/000276860. PMID: 8958538.

- Appasamy M, Lam C, Alm J, Chadwick AL. Trigger Point Injections. Phys Med Rehabil Clin N Am. 2022 May;33(2):307-333. doi: 10.1016/j.pmr.2022.01.011. PMID: 35526973; PMCID: PMC9116734.

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Holden L, Gallagher EJ. Comparative Analgesic Efficacy of Oxycodone/Acetaminophen Versus Hydrocodone/Acetaminophen for Short-term Pain Management in Adults Following ED Discharge. Acad Emerg Med. Nov 2015;22(11):1254-60. doi:10.1111/acem.12813

- Chang AK, Bijur PE, Lupow JB, Gallagher EJ. Comparative Analgesic Efficacy of Oxycodone/Acetaminophen vs Codeine/Acetaminophen for Short-Term Pain Management Following ED Discharge. Pain Med. Dec 2015;16(12):2397-404. doi:10.1111/pme.12830

- Dowell D, Haegerich TM, Chou R. CDC Guideline for Prescribing Opioids for Chronic Pain–United States, 2016. JAMA. Apr 19 2016;315(15):1624-45. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1464

- Costigan M, Scholz J, Woolf CJ. Neuropathic pain: a maladaptive response of the nervous system to damage. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:1-32. doi:10.1146/annurev.neuro.051508.135531

- Treede RD, Jensen TS, Campbell JN, et al. Neuropathic pain: redefinition and a grading system for clinical and research purposes. Neurology. Apr 29 2008;70(18):1630-5. doi:10.1212/01.wnl.0000282763.29778.59

- Derry S, Rice AS, Cole P, Tan T, Moore RA. Topical capsaicin (high concentration) for chronic neuropathic pain in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017 Jan 13;1(1):CD007393. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD007393.pub4. PMID: 28085183; PMCID: PMC6464756.

- Park J, Park HJ. Botulinum Toxin for the Treatment of Neuropathic Pain. Toxins (Basel). 2017 Aug 24;9(9):260. doi: 10.3390/toxins9090260. PMID: 28837075; PMCID: PMC5618193.

- Lovett PB, Sule HP, Lopez BL. Sickle cell disease in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. Aug 2014;32(3):629-47. doi:10.1016/j.emc.2014.04.011

- Tanabe P, Silva S, Bosworth HB, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing two vaso-occlusive episode (VOE) protocols in sickle cell disease (SCD). Am J Hematol. 02 2018;93(2):159-168. doi:10.1002/ajh.24948

- Tripette J, Loko G, Samb A, et al. Effects of hydration and dehydration on blood rheology in sickle cell trait carriers during exercise. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. Sep 2010;299(3):H908-14. doi:10.1152/ajpheart.00298.2010

- van Tuijn CFJ, Gaartman AE, Nur E, Rijneveld AW, Biemond BJ. Incentive spirometry to prevent acute chest syndrome in adults with sickle cell disease; a randomized controlled trial. Am J Hematol. 2020 Jul;95(7):E160-E163. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25805. Epub 2020 May 1. PMID: 32242978; PMCID: PMC7317710.

- Brandow AM, Carroll CP, Creary S, et al. American Society of Hematology 2020 guidelines for sickle cell disease: management of acute and chronic pain. Blood Advances. 2020;4(12):2656-2701. doi:10.1182/bloodadvances.2020001851

- Neri CM, Pestieau SR, Darbari DS. Low-dose ketamine as a potential adjuvant therapy for painful vaso-occlusive crises in sickle cell disease. Paediatr Anaesth. Aug 2013;23(8):684-9. doi:10.1111/pan.12172

- Schoenfeld EM, Pekow PS, Shieh MS, Scales CD, Lagu T, Lindenauer PK. The Diagnosis and Management of Patients with Renal Colic across a Sample of US Hospitals: High CT Utilization Despite Low Rates of Admission and Inpatient Urologic Intervention. PLoS One. 2017;12(1):e0169160. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0169160

- Stein A, Ben Dov D, Finkel B, Mecz Y, Kitzes R, Lurie A. Single-dose intramuscular ketorolac versus diclofenac for pain management in renal colic. Am J Emerg Med. Jul 1996;14(4):385-7. doi:10.1016/s0735-6757(96)90055-8

- Duttchen KM, Lo A, Walker A, et al. Intraoperative ketorolac dose of 15mg versus the standard 30mg on early postoperative pain after spine surgery: A randomized, blinded, non-inferiority trial. J Clin Anesth. Sep 2017;41:11-15. doi:10.1016/j.jclinane.2017.05.013

- Bektas F, Eken C, Karadeniz O, Goksu E, Cubuk M, Cete Y. Intravenous paracetamol or morphine for the treatment of renal colic: a randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Ann Emerg Med. Oct 2009;54(4):568-74. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.06.501

- Safdar B, Degutis LC, Landry K, Vedere SR, Moscovitz HC, D’Onofrio G. Intravenous morphine plus ketorolac is superior to either drug alone for treatment of acute renal colic. Ann Emerg Med. Aug 2006;48(2):173-81, 181.e1. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.03.013

- Abbasi S, Bidi N, Mahshidfar B, et al. Can low-dose of ketamine reduce the need for morphine in renal colic? A double-blind randomized clinical trial. Am J Emerg Med. Mar 2018;36(3):376-379. doi:10.1016/j.ajem.2017.08.026