Authors: Ashley Weisman, MD (EM Attending Physician, University of Vermont Medical Center) and Catherine Platt, PharmD (EM Clinical Pharmacist, University of Vermont Medical Center) // Edited by: Kayvan Moussavi, PharmD, BCCCP (Faculty, Clinical Education, Providence St. Joseph Hospital Orange; Assistant Professor, Department of Pharmacy Practice / College of Pharmacy, Marshall B. Ketchum University); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); Brit Long, MD

Case

You are working in a rural, critical access hospital two hours from the nearest tertiary center. The 6 bed ED is covered by a solo physician and one RN. It’s 2AM, and a 79-year-old male presents with fever and dyspnea. You place the patient on the monitor and see a wide complex tachycardia and a blood pressure of 81/42 mmHg. You administer 50 mcg of fentanyl IV and attempt cardioversion; however, this tachycardia is refractory to three attempts at 200 joules. You ask your nurse teammate to prepare a norepinephrine drip and an amiodarone bolus and infusion. You fear for the worst, so you ask him to prepare a vasopressin drip and push dose epinephrine boluses as well. Your nurse colleague kindly reminds you that you are not in the big city anymore. This is a rural ED, there is no ED pharmacist, and we need to mix all our own medications. How do you prepare them? Can you mix them in normal saline (0.9% sodium chloride) or dextrose 5% in water (D5W)? Are they all Y site compatible if you have only one peripheral IV? What resources can you use to find this information?

Introduction

Rural EDs operate with many limited resources including limited or no onsite pharmacy support and single provider and nurse coverage, especially at night. Rural EDs often stock fewer premixed critical medications, since they tend to be more expensive, expire more quickly, and are less frequently used than in tertiary centers (1-4). Thus, single nurse and physician teams in rural EDs often find themselves mixing and administering numerous essential medications to provide care for critically ill patients. If you are unfamiliar with medication preparation, there may be significant delays in initiating life-saving therapies. Therefore, it is important for all ED providers to be comfortable with preparation, dosing, and administration of IV medications. Fortunately, the list of medications that you need (and have) to care for critically ill patients in rural hospitals is quite small. Mastering the preparation, dosing, and administration of this small but mighty subset of critical medications dramatically improves your efficiency and reduces your cognitive load when caring for sick patients.

Case Resolution

I came across this very patient in a rural ED a few years ago with no pharmacy coverage and no idea how to mix the medications we needed. Our two-woman MD/RN team spent the night running around like crazy, rifling through our pharmacy’s old paper ‘cookbook’, supplementing with Lexicomp and Google, mixing a med, cross checking dosing and Y site compatibility on Micromedex, and hoping it matched the concentrations listed in our IV infusion pump library. When it did not, we sighed, and triple checked our arithmetic as we manually entered the medication and calculated the infusion rate. The patient made it to tertiary care and had a good outcome, but it wasn’t pretty.

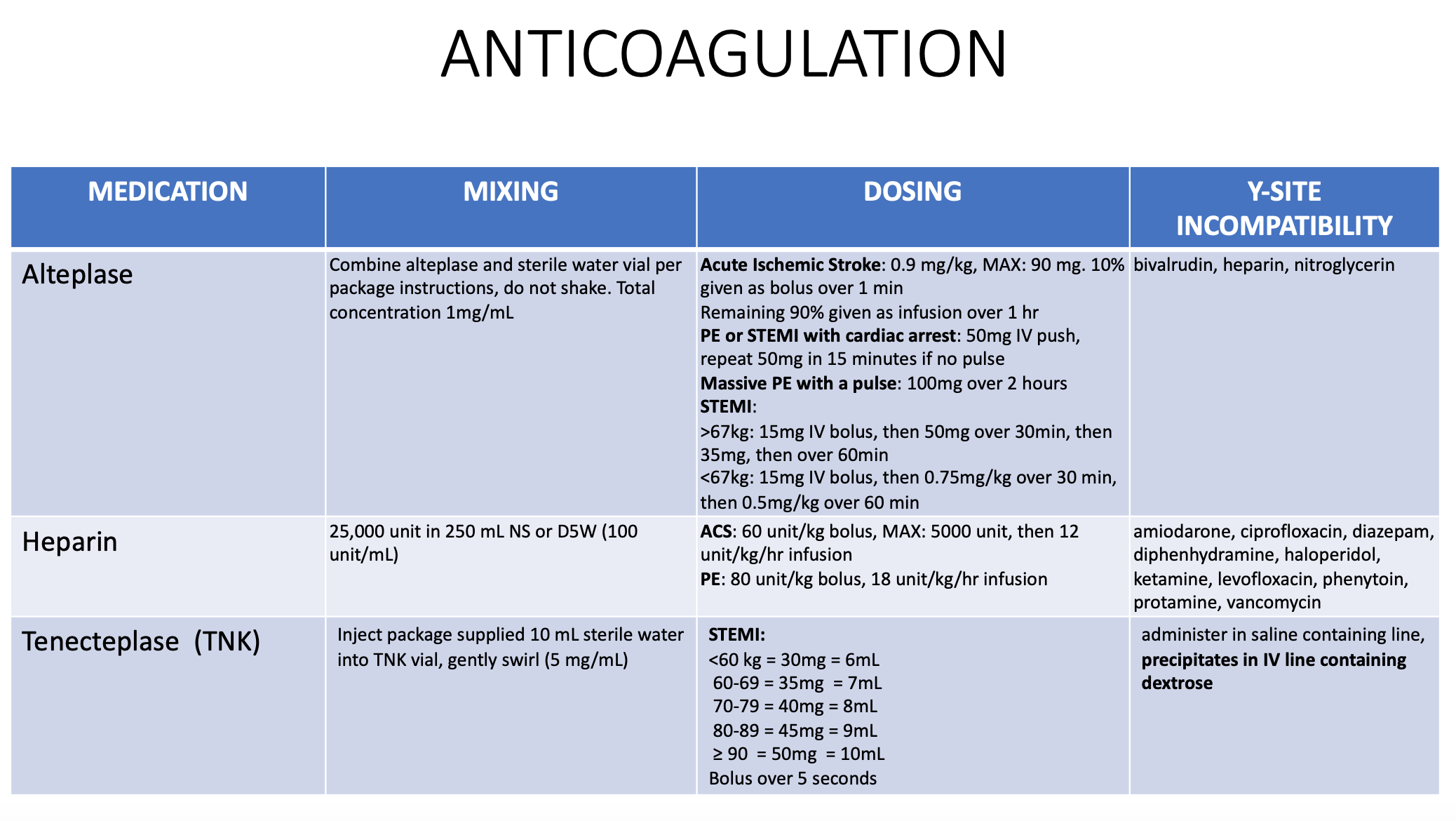

ED/Critical Care Pharmacy Recipe Cards

Following this case, I conferred with physician, nurse, prehospital, and pharmacist colleagues working in rural and tertiary EDs. We generated a short list of important critical care medications and created a set of critical care pharmacy “recipe cards” These cards summarize preparation, dosing, and compatibility, and can be tailored to your hospital formulary and infusion pump library. We have used these many times in our small EDs and found them very helpful. We hope others will find them useful.

General Approach to Preparing and Administering IV medications

Begin with hand hygiene and aseptic technique, including wiping the tops of vials with alcohol swabs before drawing up medications. Gather your supplies – medication vials, solvent (NS or D5W) in an appropriately sized bag, syringes to draw up medications and remove solvent, IV tubing, IV infusion pump. Label all mixed medications with name, concentration, date, and time prepared. Prime your IV tubing. If you are using a medication concentration that matches your pump library, you will be able to input the medication and concentration, select your dose, and the pump will do the math and ensure the correct infusion rate. If the concentration you mix does not match your library, be prepared to do the math yourself. For example, you prepare norepinephrine at 4mg/250mL, but your pump library only has the 8mg/250mL concentration, and the infusion rate must be entered in mL/hr. If you want to run this 4mg/250mL norepi at 10mcg/min, you will need to manually convert mcg/min to mL/hr and enter an infusion rate of 37mL/hr (recommend this calculator – https://www.manuelsweb.com/McgPerMin.htm).

When mixing medications, it is also helpful to be aware of how to account for overfill and drug volume. Commercially available parental solutions are labeled with a given volume – 100, 250, 500, 1000 mL – but are slightly overfilled to account for evaporative water losses over time. Thus, the actual volume is a little larger than listed and concentrations will vary slightly based on the age and storage conditions of the bag. When mixing a medication infusion, you can do one of three things: 1) just add the medication to the solvent, 2) withdraw some solvent to account for drug volume, 3) withdraw more solvent to account for both overfill and drug volume. In our context, the rural ED with a crashing patient, we are most often choosing option 1, tolerating a minor inaccuracy in the infusion’s concentration in favor of ease and speed, and titrating our infusions to affect anyway. However, when the volume of drug you are adding is greater than 10% of the total volume of your solvent, we do recommend option 2, removing the volume of solvent equivalent to the volume of drug. For example, to mix a 1mg/mL diltiazem infusion using a 125ml bag of NS, remove 25mL NS from the 125mL bag, then add 125mg diltiazem reconstituted in 25mL sterile water (total volume 125mL). Alternatively, you could use a 100mL bag of NS and add 125mg diltiazem in 25mL sterile water for a total volume of about 125mL (likely closer to 130mL due to overfill), and a concentration of about 1mg/mL, titrated to desired heart rate.

Disclaimer: These mixing and administration instructions provide rapid, general guidelines to assist in caring for critical patients with limited staff. Other compounding and dosing options may exist. It is ultimately the provider’s responsibility to make the best compounding and dosing for each patient. Compatibility lists include medications frequently used in critically ill patients but are not exhaustive. We strongly recommend consulting a comprehensive reference such as Micromedex or Lexicomp as soon as possible.

Abbreviations: Normal saline (NS), Dextrose 5% in water (D5W), as needed (PRN), paroxysmal ventricular tachycardia (pVT), ventricular fibrillation (VF), diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA), Hyperosmolar hyperglycemic non-ketoacidosis (HHNK), Intracranial Pressure (ICP), Acute coronary syndrome (ACS), Pulmonary embolism (PE).

Take-Home Points

- Whether you work in a rural ED, a resource-limited ED, or a tertiary center filled with more sick patients than your ED pharmacists can cover, you need to be able to care for patients without the pharmacist, including mixing and dosing your own medication infusions. This can be very challenging when you are simultaneously caring for several sick patients, so preparation and practice are key.

- Familiarize yourself with the basic principles of mixing infusions and operating IV pumps.

- Review your hospital formulary and commit to memory the mixing instructions and dosing for a handful of your most essential resuscitation medications.

- Understand what resources (including this guide) are available to assist you when your next critical patient arrives and have them readily available. This will dramatically improve your efficiency, confidence, and cognitive load during these resuscitations.

References

General References for preparation, dosing, and compatibility: Micromedex, Lexicomp, Clinical Pharmacology

- micromedexsolutions.com

- https://www.wolterskluwer.com/en/solutions/lexicomp/resources/lexicomp-user-academy/trissels-iv-compatibility-databases

- https://www.clinicalpharmacology-ip.com

- https://www.manuelsweb.com/McgPerMin.htm

Peer Reviewed Publications

- Casey MM, Moscovice IS, Davidson G. Pharmacist staffing, technology use, and implementation of medication safety practices in rural hospitals. J Rural Health. 2006 Fall;22(4):321-30.

- Bennett, Christopher L., et al. “National Study of the Emergency Physician Workforce, 2020.” Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2020 Dec; 76(6): 695–708.

- Mk, Hall, et al. “State of the National Emergency Department Workforce: Who Provides Care Where?” Annals of Emergency Medicine. 2018 Sept; 72(3).

- Walker SE, Law S, Garland J, Fung E, Iazzetta J. Stability of norepinephrine solutions in normal saline and 5% dextrose in water. Can J Hosp Pharm. 2010 Mar;63(2):113-8

- Sharifi M, Bay C, Skrocki L, Rahimi F, Mehdipour M; “MOPETT” Investigators. Moderate pulmonary embolism treated with thrombolysis (from the “MOPETT” Trial). Am J Cardiol. 2013 Jan 15;111(2):273-7.

- Stemple K, DeWitt KM, Porter BA, Sheeser M, Blohm E, Bisanzo M. High-dose nitroglycerin infusion for the management of sympathetic crashing acute pulmonary edema (SCAPE): A case series. Am J Emerg Med. 2021 Jun;44:262-266.

- Mathew R, Kumar A, Sahu A, Wali S, Aggarwal P. High-Dose Nitroglycerin Bolus for Sympathetic Crashing Acute Pulmonary Edema: A Prospective Observational Pilot Study. J Emerg Med. 2021 Sep;61(3):271-277.

- Firestone RL, Parker PL, Pandya KA, Wilson MD, Duby JJ. Moderate-Intensity Insulin Therapy Is Associated With Reduced Length of Stay in Critically Ill Patients With Diabetic Ketoacidosis and Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State. Crit Care Med. 2019 May;47(5):700-705.

- Dalziel SR, Borland ML, Furyk J, Bonisch M, Neutze J, Donath S, Francis KL, Sharpe C, Harvey AS, Davidson A, Craig S, Phillips N, George S, Rao A, Cheng N, Zhang M, Kochar A, Brabyn C, Oakley E, Babl FE; PREDICT research network. Levetiracetam versus phenytoin for second-line treatment of convulsive status epilepticus in children (ConSEPT): an open-label, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2019 May 25;393(10186):2135-2145.

- Glauser T, Shinnar S, Gloss D, Alldredge B, Arya R, Bainbridge J, Bare M, Bleck T, Dodson WE, Garrity L, Jagoda A, Lowenstein D, Pellock J, Riviello J, Sloan E, Treiman DM. Evidence-Based Guideline: Treatment of Convulsive Status Epilepticus in Children and Adults: Report of the Guideline Committee of the American Epilepsy Society. Epilepsy Curr. 2016 Jan-Feb;16(1):48-61.

- Kapur J, Elm J, Chamberlain JM, Barsan W, Cloyd J, Lowenstein D, Shinnar S, Conwit R, Meinzer C, Cock H, Fountain N, Connor JT, Silbergleit R; NETT and PECARN Investigators. Randomized Trial of Three Anticonvulsant Medications for Status Epilepticus. N Engl J Med. 2019 Nov 28;381(22):2103-2113.

- Alkazemi A, McLaughlin KC, Chan MG, Schontz MJ, Anger KE, Szumita PM. Safety of Intravenous Push Levetiracetam Compared to Intravenous Piggyback at a Tertiary Academic Medical Center: A Retrospective Analysis. Drug Saf. 2022 Jan;45(1):19-26.

- Spasovski G, Vanholder R, Allolio B, Annane D, Ball S, Bichet D, Decaux G, Fenske W, Hoorn EJ, Ichai C, Joannidis M, Soupart A, Zietse R, Haller M, van der Veer S, Van Biesen W, Nagler E; Hyponatraemia Guideline Development Group. Clinical practice guideline on diagnosis and treatment of hyponatraemia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2014 Feb 25;170(3):G1-47.

- Verbalis JG, Goldsmith SR, Greenberg A, Korzelius C, Schrier RW, Sterns RH, Thompson CJ. Diagnosis, evaluation, and treatment of hyponatremia: expert panel recommendations. Am J Med. 2013 Oct;126(10 Suppl 1):S1-42.

- Maguigan KL, Dennis BM, Hamblin SE, Guillamondegui OD. Method of hypertonic saline administration: effects on osmolality in traumatic brain injury patients. J Clin Neurosci. 2017;39:147-150.

- Cruz KCE, Churchwell MD, Mauro VF, Boddu SHS. Physical compatibility of levetiracetam injection with heparin, dobutamine, and dopamine. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2018 Apr 15;75(8):510-512.