Authors: Marlee Hahn, MD (EM Resident Physician, University of Washington), Joshua Villarreal, PharmD (ED Pharmacist, University of Washington Medical Center), and Jeff Riddell, MD (@Jeff_Riddell, EM Attending Physician / Medical Education Research Fellow, University of Washington) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK, EM Attending Physician, UT Southwestern Medical Center / Parkland Memorial Hospital) and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Image reproduced from americanpregnancy.org[1]

CASE:

A 26 year-old G4P3 Spanish-speaking female at 20 weeks GA presents with husband after a “fainting episode” at home. You begin gathering history in what little Spanish you know as the medical assistant gets the interpreter phone. Her husband is describing the preceding events, when she suddenly becomes unresponsive, her eyes roll back, and she begins convulsing in an apparent generalized tonic-clonic seizure.

Your nurse notices this, comes quickly to bedside, and asks you, “What meds do you want to give?”

You stare wide-eyed at her gravid abdomen as you wrack your brain for what you could safely give to halt her seizure? What if she needs intubation? What if she codes? Can you do an xray? CT? Give contrast?

QUESTIONS:

Which “Go To” medications can most safely be given during pregnancy?

Which medications should you avoid during pregnancy?

What resources exist to help emergency providers with these decisions?

BACKGROUND:

Emergency providers have a uniquely difficult role in evaluating and treating patients under stressful scenarios and with incomplete information. It is our responsibility to weigh the benefits of a particular intervention, medication, or diagnostic study with its risks, and this responsibility can be further magnified in the case of pregnancy.

Although the majority of birth defects are attributable to unknown or unavoidable causes, we must take seriously our role in contributing to modifiable factors, particularly due to medication and radiation exposures[2]. Unfortunately there is incomplete or poor data on the use of most medications in pregnancy[3]. Although we have a responsibility to minimize harm while attempting to maximize treatment benefits, for emergency providers, this decision is often simplified – Treat the emergency.

ARE THEY PREGNANT?

One pitfall emergency providers encounter is that many patients do not know they are pregnant and their complaints often do not warrant testing for pregnancy. According to a large retrospective data analysis, only 22% of reproductive-aged women seen in the ED were tested for pregnancy prior to receiving or being prescribed “teratogenic” medications (defined as class D or X)[4] (Figure 1). Of these patients, it was noted that the most common medications prescribed were benzodiazepines, antibiotics, and antiepileptic medications, and most commonly for diagnoses of psychiatric, musculoskeletal, and cardiac nature. Although there is much debate about which medications actually classify as teratogenic, providers should have basic knowledge of the safest and least safe medication choices to employ when working in the Emergency Department.

Figure 1. Pregnancy testing frequency by FDA pregnancy risk category4

TERATOGENS

There is consensus across many specialties that data on teratogens is inadequate3. The majority of the evidence is derived from animal research, retrospective analyses, case reports and cohort studies, as ethics preclude prospective human studies[5]. It is, however, known that there are significant associations between in utero pharmaceutical exposures and birth defects, thought to contribute to 2-3% of all birth defects, ranging from subtle or delayed to fetal non-viability6. These include the following medications:

Table 1. Known Human Teratogens and Developmental toxins5,[6]

DRUG LABELING

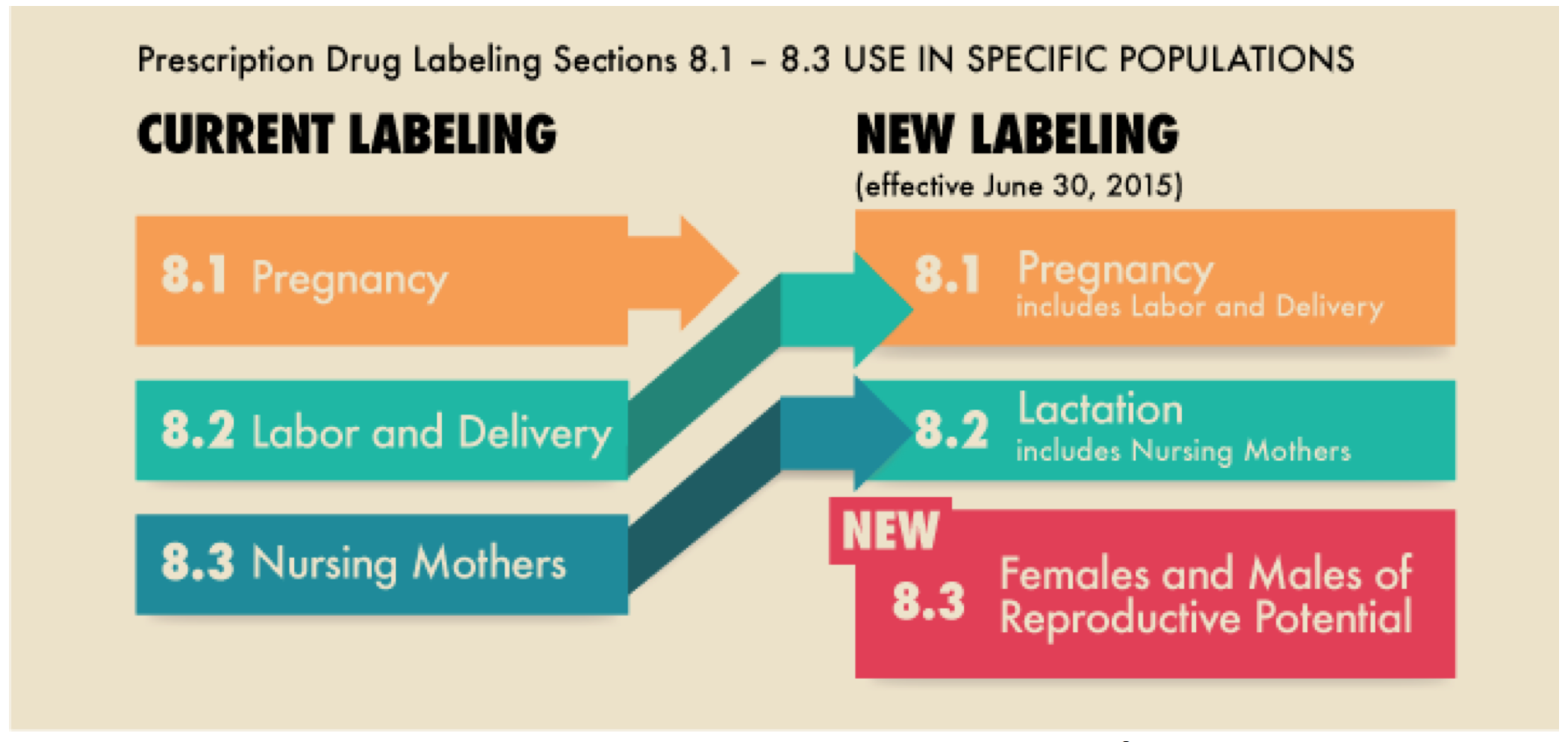

The FDA drug classification system previously employed the use of letter grading, A, B, C, D, E, and X, however for decades these have been criticized as they “did not accurately and consistently communicate differences in degrees of fetal risk”, leading to misuse or misinterpretation by clinicians[7]. In response, in 2014 the FDA abandoned the letter classes, adjusting the Drug Labeling system to redefine and clarify recommendations for use in pregnancy, lactation, and now also patients with reproductive potential.

Image reproduced from fda.gov[8]

Medications now are labeled with drug-specific explanatory data outlining the generalized safety profile, however without clear categorization. Although this may reduce the “misuse” of categorizations, this proposes yet another challenge to the on-the-go MDs who desire a more discrete ‘yes’ or ‘no’ answer regarding the safety of medications.

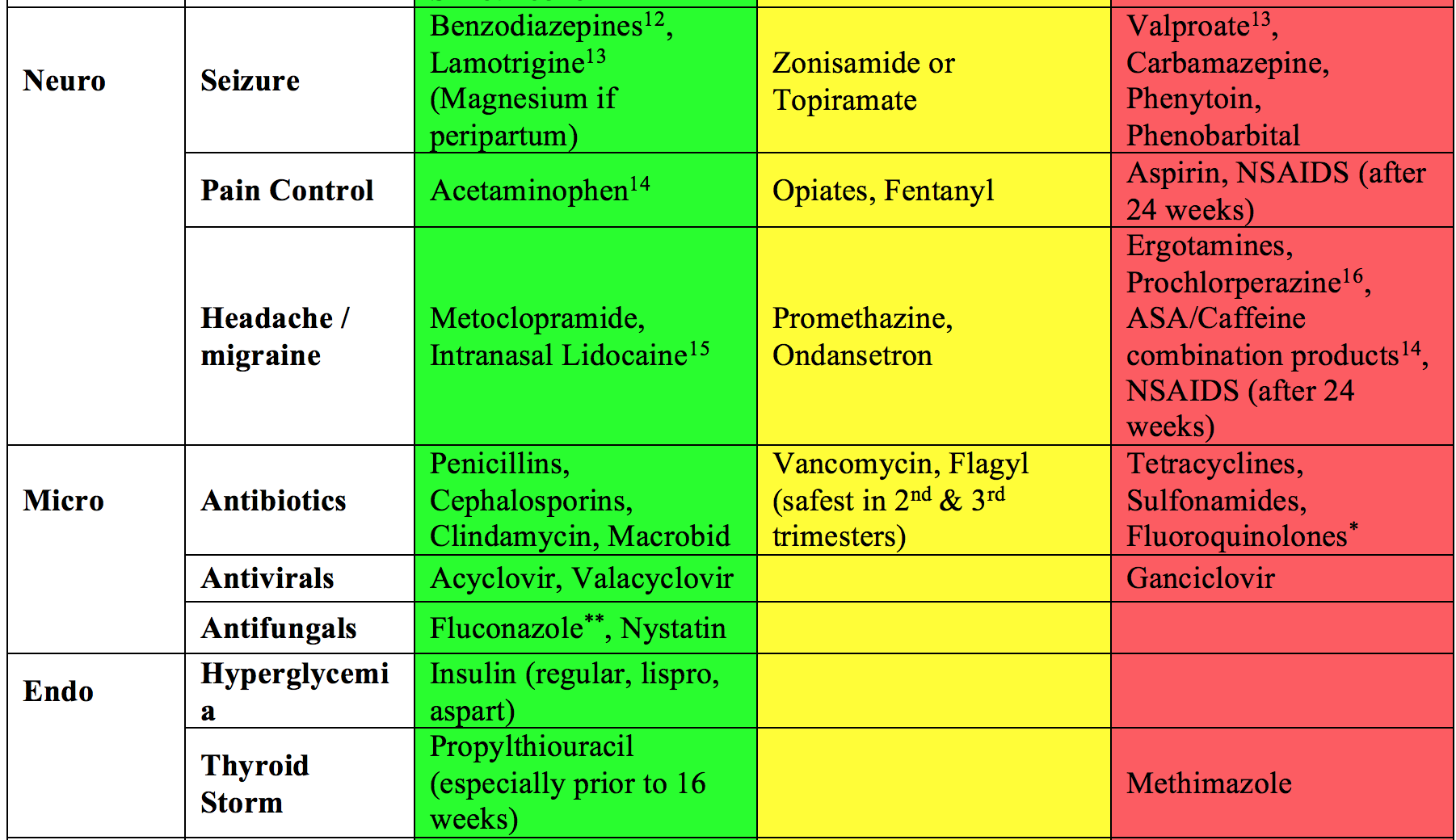

GO-TO MEDICATIONS

Given the lack of well-controlled primary literature, the following table seeks to provide a consolidated categorization for first line “GO-TO” medications, second line, and relatively dangerous, “AVOID” medications for specific ED presentations in pregnancy. This list is by no means exhaustive however allows for an on-the-go “pocket-card” catered specifically to emergency providers.

Table 2. Multi-Resource Derivation of Common Emergency Department Medication Use in Pregnancy5,[18],[19],[20] (data gathered from these resources unless otherwise noted)

*Long thought to be unsafe in pregnancy due to bone/ligament threat, however newer data has found largely reassuring results, that said avoid if other preferred option available[21]

**Data supports safe use of one-time dose of Fluconazole however less data is available for long term course

***TPA does not cross placenta but pregnancy is considered a relative contraindication for use

DOSING & PHARMACOKINETICS:

Generally a specific dose recommendation would be preferable when evaluating medication use in special populations. In pregnancy, recall that physiology, and therefore pharmacokinetics, changes in many ways[22]–most notably:

- Changes in total body weight & fat composition

- Total body water expansion

- Delayed gastric emptying & prolonged transit times

- Increased extracellular fluid and total body water

- Increased cardiac output, SV, and HR

- Decreased albumin concentration with reduced protein binding

- Increased organ perfusion / blood flow / GFR

- Changes in hepatic enzyme activity

Despite these known changes, there are no well-studied dose adjustments in pregnancy, which can often lead to both under and overdosing when standard weight based doses are used. Despite this, there is also no consistent literature to support alteration of dosing from standard adult doses. If you have access to one, an ED pharmacist can assist with dosing decisions.

RADIATION:

There are modest bodies of data on radiation exposure extrapolated from survivors of chemical warfare. Effects of radiation are directly related to gestational age (GA) at time of exposure. The first 14 days are most likely to have lethal effect on fetus, whereas exposure at GA 2-8 weeks, during organogenesis, is most likely to result in congenital malformations. Exposures between 8-15 weeks are most associated with mental retardation and microcephaly. When evaluating pregnant women in the Emergency Department, the use of Ultrasound and MRI are by far the safest, without known harm or risk to fetus. The use of X-Ray and CT should be evaluated case by case with a radiologist to adequately assess the risks and benefits of the study. In life threatening cases, radiologic evaluation is warranted if directly related to survival of the mother, and therefore fetus2.

TAKE HOME POINTS:

- Treat the emergency: Sick mom = sick baby therefore BENEFIT >> RISK

- Have your “GO-TO” and “AVOID” meds memorized or easily accessible (Table 2, above)

- Strongly consider pregnancy testing of reproductive age women before administering meds or writing new prescriptions when possible and practical.

- When in doubt, consult a pharmacist or specialist for more complicated medications and imaging decisions.

RESOURCES

Although this article may be assistive, it is not complete in referencing a majority of less common medications and all EPs should have a resource they trust and can utilize at all hours. Below are several recommendations:

Live Resources:

– Your Pharmacists (ED or inpatient)

– Consultants: OB/GYN or specialist related to issue in question (ID, Neuro, Surgery, etc.)

Online Databases:

- Micromedex REPRORISK database

- REPROTOX (www.reprotox.org)

- Uptodate

- Epocrates mobile app

- LactMed (for lactation)

- drugs.com/pregnancy

Disclosure: This is not an endorsement for specific resource but rather the opportunity to provide options for information access.

References/Further Reading:

[1] American Pregnancy Association. Medications & Pregnancy. 2017. http://americanpregnancy.org/medication/medication-and-pregnancy. Accessed April 1, 2017.

[2] Harris BS, Bishop KC, Kemeny HR, Walker JS, Rhee E, Kuller JA. Risk Factors for Birth Defects. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2017 Feb;72(2):123-135.

[3] Riley LE, Cahill AG, Beigi R, Savich R, Saade G. Improving Safe and Effective Use of Drugs in Pregnancy and Lactation: Workshop Summary. Am J Perinatol. 2017 Jan 31.

[4] Goyal MK, Hersh AL, Badolato G, Luan X, Trent M, Zaoutis T, Chamberlain JM. Underuse of pregnancy testing for women prescribed teratogenic medications in the emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2015 Feb;22(2):192-6.

[5] Marx, J. A., & Rosen, P. Rosen’s emergency medicine: Concepts and clinical practice (8th ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. 2014.

[6] Shephard TH, Lemire RJ. Catalog of Teratogenic Agents. 12th Ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 2007.

[7] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. Content and Format of Labeling for Human Prescription Drug and Biological Products; Requirements for Pregnancy and Lactation Labeling. 2014. www.federalregister.gov/documents/2014/12/04/2014-28241/content-and-format-of-labeling-for-human-prescription-drug-and-biological-products-requirements-for. Accessed April 09 2017.

[8] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Food and Drug Administration. 2014. https://www.fda.gov/ucm/groups/fdagov-public/documents/image/ucm425205.png. Accessed April 9 2017.

[9] Yaksh A, van der Does LJ, Lanters EA, de Groot NM. Pharmacological Therapy of Tachyarrhythmias During Pregnancy. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev. 2016 May;5(1):41-4.

[10] Hagley MT, Cole PL. Adenosine use in pregnant women with supraventricular tachycardia. The Annals of pharmacotherapy. 1994, Vol.28(11), p.1241-1242.

[11] Cooper WO et al. Major congenital malformations after first-trimester exposure to ACE inhibitors. N Engl J Med. 2006 Jun 8;354(23):2443-51.

[12] Vitale, SG et al. Psychopharmacotherapy in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding. Obstetrical and Gynecological Survey. 2016. Vol 71(12).

[13] Shih JJ, et al, Epilepsy treatment in adults and adolescents: Expert opinion. Epilepsy Behav. 2016. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.yebeh.2016.11.018. Accessed April 8, 2017.

[14] Coluzzi F, Valensise H, Sacco M, Allegri M. Chronic pain management in pregnancy and lactation. Minerva Anestesiol 2014;80:211-24.

[15] Schoen JC, Campbell RL, Sadosty AT. Headache in Pregnancy: An Approach to Emergency Department Evaluation and Management. Western Journal of Emergency Medicine: Integrating Emergency Care with Population Health. West J Emerg Med. 2015 Mar;16(2):291-301.

[16] Contag SA, Mertz HL, Bushnell CD. Migraine during pregnancy: is it more than a headache? Nat Rev Neurol. 2009;5:449-56.

[17] Webb, JA, Thomsen HS, Morcos SK. The use of iodinated and gadolinium contrast media during pregnancy and lactation. Eur Radiol.2005.15:1234-40.

[18] Shephard TH, Lemire RJ. Catalog of Teratogenic Agents. 12th Ed. Baltimore, MD: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 2007.

[19] Therapeutic Goods Administration, Australian Drug Evaluation Committee. Prescribing medicines in pregnancy; An Australian categorisation of risk of drug use in pregnancy. Commonwealth of Australia. 4th Ed. 1999. https://web.archive.org/web/20070316054726/http://www.tga.gov.au/docs/pdf/medpreg.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2017.

[20] Micromedex Solutions. Truven Health Analytics, Inc. Ann Arbor, MI. Available at: http://www.micromedexsolutions.com. Accessed April 12, 2014.

[21] Padberg et al. Observational Cohort Study of Pregnancy Outcome after First- Trimester Exposure to Fluoroquinolones. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014 Aug; 58(8): 4392–4398.

[22] Donald R. Mattison, Clinical Pharmacology During Pregnancy. 1st Ed. Elsevier. 2013. https://www-clinicalkey-com.offcampus.lib.washington.edu/#!/content/book/3-s2.0-B9780123860071010011. Accessed April 4, 2017.