Author: Richard Slama, MD, LT (Emergency Medicine Physician, Naval Medical Center Portsmouth) // Edited by: Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK), Brit Long, MD (@long_brit, EM Resident at SAUSHEC, USAF)

Introduction

The presentation of muffled heart sounds, jugular venous distension (JVD), and hypotension sound familiar? It should as it has been a widely used triad in most textbooks and medical school lectures to describe cardiac tamponade (CT). In reality this triad of findings may only be present in ~40% of patients.1 Briefly, CT can be categorized into true tamponade (effusion around the heart), constrictive tamponade (due to pericardium not stretching), or a constrictive with effusion (both).2 Regardless of the cause, the end result of tamponade is compression of the chambers of the heart and impedance of venous return leading to decreased cardiac output. The question then becomes what is the best way to diagnose and treat this condition in the emergency department in the crashing patient? We will review a few case scenarios and discuss management and treatment of this deadly condition.

Case 1

A 75 year-old female with a history of metastatic lung cancer presents to the emergency department with hypotension, tachycardia, and obvious respiratory distress. She is given a 1 L fluid bolus and her blood pressure improves to 90/40; however, her heart rate continues to be in the high 150s. Bedside ultrasound performed shows a significant pericardial effusion with RV collapse, no pneumothorax, and no free abdominal fluid. Upon completing the ultrasound, the patient’s pressure begins to drop, and she becomes bradycardic down to the 30s and unresponsive. What is the next best course of action for this patient?

Case 2

A 22 year-old male with no major medical history presents to the emergency department with a gunshot wound to the left sternal border. On arrival the male is obviously hypotensive (65/30), tachycardic (170bpm), and in distress. As you’re performing the bedside ultrasound, you see a large pericardial effusion and bilateral lung sliding. During this procedure the patient goes into asystole. What is the most appropriate course of action for this patient?

Diagnosis

Clinical Signs

Tachycardia, hypotension, elevated JVD, pulsus paradoxus, pericardial rub, patient distress, tachypnea

Diagnostic Signs

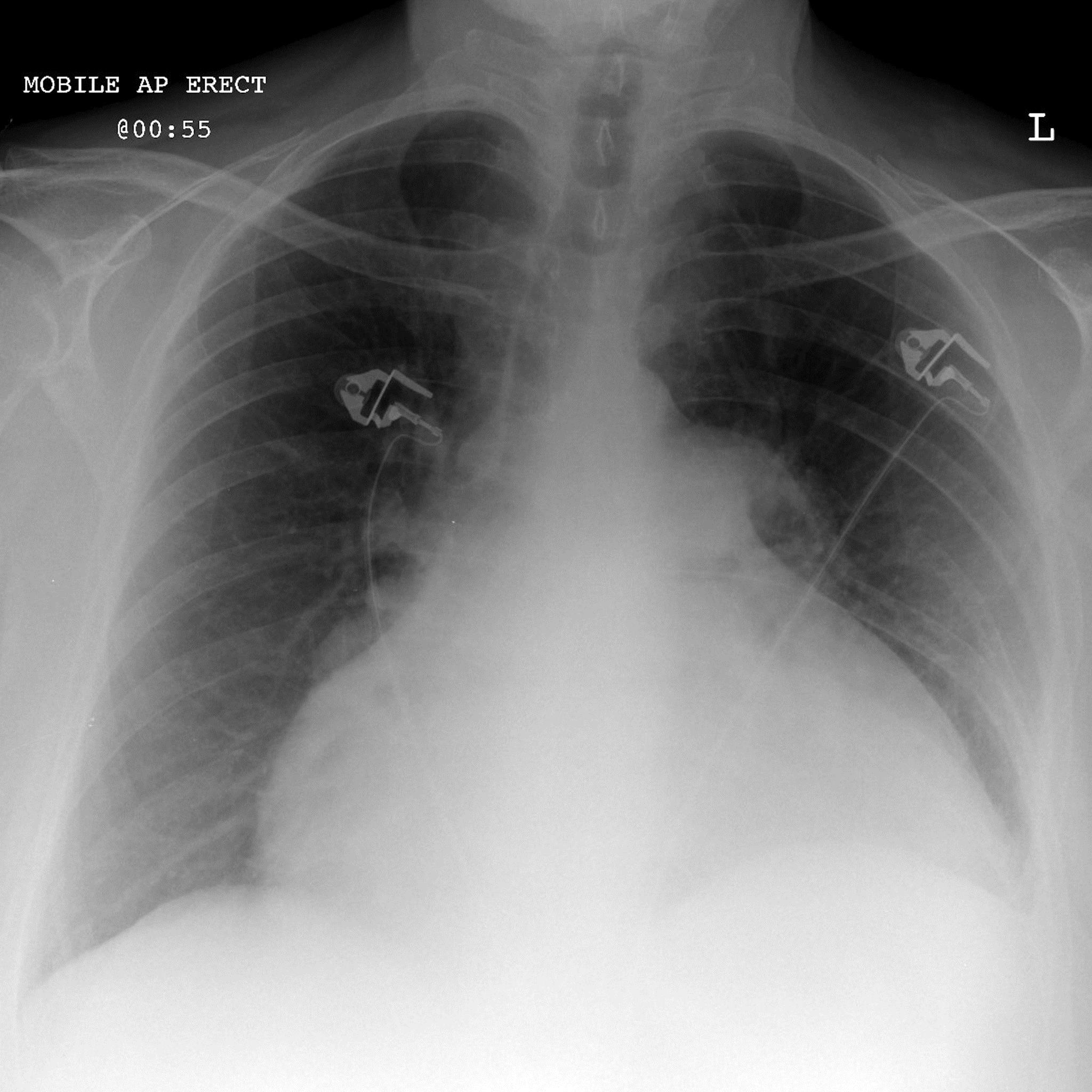

Electrical alternans – thought to be secondary to the heart “floating” within the pericardium (Image courtesy of Life In The Fast Lane)  Enlarged Cardiac Silhouette (courtesy of Radiopaedia.org) – often only present in chronic effusions, unlikely with acute presentations

Enlarged Cardiac Silhouette (courtesy of Radiopaedia.org) – often only present in chronic effusions, unlikely with acute presentations

Ultrasound – will show heart surrounded by hypoechoic fluid, possible swinging of the heart in the fluid, collapsed right atrium and/or right ventricle, enlarged and non-variable IVC (Courtesy of the Ultrasound Podcast)

Differential

PE, MI, CHF, Dissection, PTX, Sepsis, Aortic Rupture, etc…

Approach/Treatment on Case basis

For any patient for whom you suspect CT with decompensation based on clinical signs and symptoms, ultrasound should be your first diagnostic modality. While clinical signs, chest x-ray, and EKG can lead you to the diagnosis, none will prove to be as sensitive as ultrasound in diagnosing this condition. A quick parasternal long or subxiphoid view on echocardiogram performed at bedside cannot only show you effusion but can also show you the cause of the effusion such as aortic dissection.

Case 1

Malignancy is by far one of the most common causes of pericardial effusion in the United States.3 This is an all too familiar situation that is often overlooked in light of other findings in cancer patients (i.e. sepsis, pleural effusions). In the patient who is relatively stable but starting to decompensate, the first course of action is always IV, monitor, O2, airway protection, etc. Once the diagnosis has been confirmed based on bedside ultrasound and the clinical signs/symptoms, you must decide if the patient is unstable or stable. For the case of this patient who is actively crashing, the next step is to perform a bedside pericardiocentesis. As stated in most texts this procedure is “relatively simple but has a high rate of complications.”4 There are two methods:

A. Blind Pericardiocentesis (not preferred)

- Quickly sterilize the subxiphoid area with an agent of your choice.

- Insert a pericardiocentesis needle between the xiphoid and the left costal margin at a 45 degree angle.

- Remove the stylet, aim the tip of the needle towards the patients left shoulder.

- Slowly advance the needle while applying negative pressure on the syringe.

- Advance the needle until there is return of fluid.

- Do not advance further if any of the following are encountered – ischemic changes on ECG, return of pulsatile arterial blood, cardiac pulsation.

- There should be symptomatic relief for the patient upon drainage of fluid.

- At this point as much fluid as possible should be drained and if possible, the Seldinger technique may be used to place an indwelling catheter.

B. Ultrasound-guided technique (considered the standard of care)

- Visualize the largest area of pericardial fluid in either the parasternal long or apical views of the heart.

- Once identified, sterilize the area and use a sterile probe cover if time permits.

- Using the ultrasound, insert a pericardiocentesis needle over the rib into the pericardial space using continuous aspiration.

- Placement is confirmed when there is return of fluid or when the needle is visualized within the space.

- Stop for any of the reasons as listed in A6 above.

- Do not use the subxiphoid window, as there’s risk of damaging the liver.

Case 2

This presentation is one that is typical for ventricular rupture secondary to trauma from a projectile. Up to 71% of patients presenting with unstable vital signs will likely not survive. However, there have been case reports of patients surviving after low velocity projectiles entering the pericardium.5,6 In this case there is very little utility in performing a pericardiocentesis, and the next best option should be ED thoracotomy with pericardiotomy and GSW repair.

A. Left sided thoracotomy

- Pour betadine on the left side of the chest.

- Your mark is the 4th-5th intercostal space.

- Incise in 1-3 passes from sternum to posterior axillary line down to the ribs and intercostal muscles.

- Incise the intercostal muscle with mayo scissors, and insert your hand to free up the lung from the inside of the chest wall.

- Insert the Finochietto retractor and crank open (this entire process should take less than 60 seconds and will likely cause at least one person in the room to syncopize).

- Push aside the lungs, pick up the pericardium with forceps and incise parallel and ~4 cm above the phrenic nerve running along the posterior border of the heart.

- Deliver the heart, locate the GSW, and stop the bleeding using three different techniques: 1) Shove a foley into it, inflate and use this to tamponade the bleeding. 2) Suture pledgets on the myocardium 3) Staple the myocardium (by report and experience, likely the easiest and most effective).

- If your patient is still alive, now would be a great time to call your cardiovascular or trauma surgeon.

- A great overview of this can be found at: http://www.trauma.org/index.php/main/article/361

Discussion

The crashing patient with CT can be both difficult to diagnose and difficult to treat. Pericardiocentesis and thoracotomy are invasive procedures that you should probably not be using if your patient is still awake and talking. In the cases listed above, they are appropriate interventions as both patients will die if an intervention is not pursued. In summary, pericardiocentesis should be performed in any patient with evidence of a pericardial effusion and hemodynamic compromise. ED thoracotomy, while controversial, has absolute indications for the following: penetrating thoracic trauma with previously witnessed cardiac activity and blunt trauma with either witnessed loss of vital signs in the ED (or within 15 minutes) or 1,500 mL out of a chest tube.7

References/Further Reading

- Sternbach G. Claude Beck: cardiac compression triads. J Emerg Med. 1988;6(5):417-419. doi:10.1016/0736-4679(88)90017-0.

- Khandaker MH, Espinosa RE, Nishimura R a, et al. Pericardial disease: Diagnosis and management. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(6):572-593.

- Imazio M, Adler Y. Management of pericardial effusion. Eur Heart J. 2013;34(16):1186-1197. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehs372.

- Reichman EF. Chapter 36. Pericardiocentesis. In: Emergency Medicine Procedures, 2e. Vol New York, NY: The McGraw-Hill Companies; 2013. http://mhmedical.com/content.aspx?aid=57703684.

- Title: Surviving shot through the heart: Management in two cases Source: J Pakistan Med Assoc. 2015;1:31-33.

- Vu PD, Young JB, Salcedo ES GJ. Multiple complex penetrating cardiac injuries: role of civilian trauma in the education of the combat general surgeon. Mil Med. 2014;179(2).

- Slessor D, Hunter S. To Be Blunt: Are We Wasting Our Time? Emergency Department Thoracotomy Following Blunt Trauma: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Ann Emerg Med. 2015;65(3):297-307.e16. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2014.08.020.

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25441032

- http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/20800410

2 thoughts on “The Crashing Patient with Cardiac Tamponade: ED Management”

Pingback: Tamponnade et hémopéricarde | thoracotomie

Pingback: emDOCs.net – Emergency Medicine EducationEM@3AM - Cardiac Tamponade - emDOCs.net - Emergency Medicine Education