Authors: Rachel Plate, MD (EM Resident Physician, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, NC) and Kathryn T Kopec, DO (@KopecToxEM, EM Attending Physician; Medical Toxicologist, Carolinas Medical Center, Charlotte, NC) // Reviewed by: James Dazhe Cao, MD (@JamesCaoMD, Associate Professor of EM, Medical Toxicology, UTSW / Parkland Memorial Hospital); Alex Koyfman, MD (@EMHighAK); and Brit Long, MD (@long_brit)

Case:

A 47-year-old male presents to the emergency department (ED) following the ingestion of a chemical while at work. He accidentally grabbed a water bottle, he thought was his, off the break room counter and took a large drink. Immediately he realized it was not water and tried to spit out the liquid but had already swallowed most of it. The patient reports that the water bottle had been full (16 oz) and now is about half full. Upon telling his supervisor, it was discovered that another worker had placed a bathroom cleaner called “Lime-A-Way” into the empty water bottle. The product was 10% sulphamidic acid.

Initial vitals in the ED were BP 147/88 mmHg; HR 99 bpm; RR 24 breaths/min; O2 sat 98% on RA; Temp 37.8C. He was complaining of a sore throat and odynophagia. Exam demonstrated mild erythema to his posterior pharynx. He had no stridor, drooling, dyspnea or oral lesions noted.

Questions:

- What is the ED management of a caustic ingestion?

- Is any imaging required?

- What treatment, if any, is indicated?

Background/Pathophysiology:

Caustic ingestions cause injury secondary to direct contact of acidic/alkaline substances with mucosal surfaces. Acids are proton (H+) donors which typically cause coagulative necrosis, a type of non-programmed cell death caused by protein denaturation leading to cell membrane destruction. Whereas OH- donation by alkaline substances leads to liquefactive necrosis, a type of premature cell death caused hydrolysis of intracellular contents and breakdown of the cell membrane. Tissue injury develops quickly over a period of hours. (1,2)

Multiple factors contribute to the severity of injury following a caustic ingestion including:

- Time of tissue contact

- Volume or amount ingested

- pH

- Titratable acid/alkaline reserve (an intrinsic property of the chemical)

- Ability of the caustic to penetrate tissue

Long term, patients with caustic ingestions may develop strictures and have a 1000-fold increased risk of esophageal carcinoma. (1, 2)

Clinical Presentation:

Patients often present with clinical evidence of tissue damage either in their oropharynx, esophagus, or airway. However, it is possible to not have any initial physical findings and still have a significant injury in the non-visualized sections of the gastrointestinal tract.

Symptoms may include: (1,2)

- Ear/Nose/Throat:

- Oral pain, odynophagia, drooling, dysphagia

- Gastrointestinal:

- Nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain, hematemesis

- Cardiac:

- Chest pain

- Respiratory:

- Difficulty breathing, coughing or stridor, airway compromise

Diagnosis:

Caustic ingestions are primarily a clinical diagnosis made from components of the patient’s history and supported by the physical exam. Laboratory testing may include CBC, BMP, type and screen, VBG/ABG, PT/INR and lactate. The decision to obtain labs is based on the history, physical exam findings, intent of the ingestion and characteristics of the acid/alkali ingested. (2) Initial imaging may include an upright chest x-ray (CXR) and/or abdominal x-ray to assess for pneumomediastinum or pneumoperitoneum. (1, 2)

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) may be indicated to assess for direct tissue damage, grade the severity of injury to prognosticate the risk for long-term morbidity. EGD should be performed within 24 hours, as beyond this timeframe the patient is at high-risk for iatrogenic perforation. (2) Subsequent EGDs may be performed 2 weeks post-ingestion when perforation risk is lower.

EGD is recommended within the first 24-48 hours for: (3,4)

- Intentional ingestions

- Stridor alone

- Unintentional ingestions with 1 out of the following 3: vomiting, drooling, or inability to tolerate oral intake (per os [PO]) require observation overnight and repeat PO trial the following morning. If remain unable to tolerate PO then endoscopy is recommended

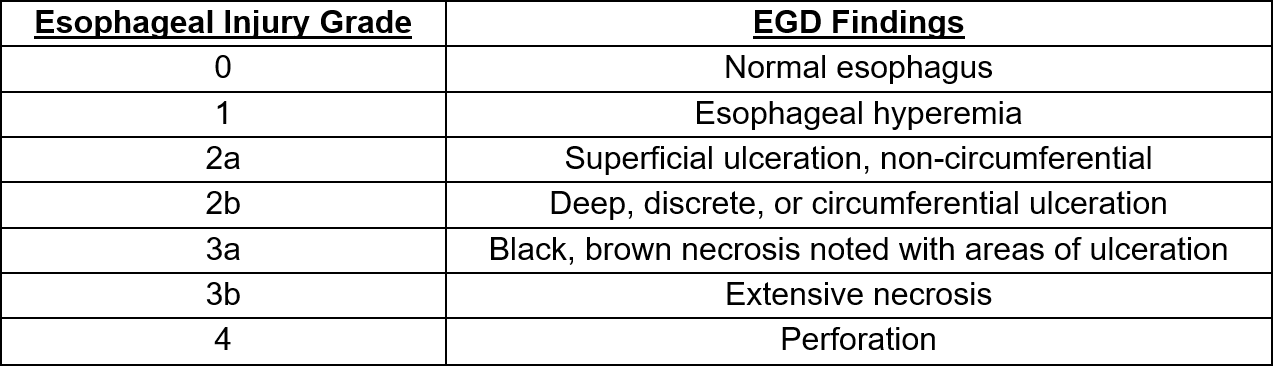

Mucosal esophageal injury is graded on a scale from 0-4 based on EGD findings. (5)

CT chest/abdomen with IV and oral contrast can be an alternative or supplement to EGD in some cases. (2, 4-6) Depending on the patient’s clinical presentation, availability of consultants and possible need for transfer, CT scan can help determine presence of transmural and possibly mucosal damage prior to EGD. (4,6) Further, if a patient presents outside of the 24-hour window for EGD, CT scan can help identify injury.

Management:

Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment. Decontaminate the patient as soon as possible by removing clothes and rinsing exposed affected areas with water. Secure the patient’s airway if there is stridor or other signs of respiratory distress. Establish IV access early and give IV fluids if the patient is symptomatic as caustics may result in third spacing. (1) Provide symptomatic treatment with pain medications and anti-emetics as needed.

Providers should remember what not to do in these cases as well:

- Induce emesis

- Attempt neutralization of the ingested agent

- Administer activated charcoal to these patients

Severe ingestions may result in hollow viscus perforation or fistula formation with major arteries which would require surgical consultation. Some evidence suggests benefit with the administration of glucocorticoids with grade IIb esophageal injuries to prevent esophageal stricture formation. (1,4,7) The decision to administer steroids should be made in discussion with our gastroenterology (GI) colleagues. Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and histamine (H2) blockers are often given and may be helpful, though further study is required. (2, 8) Finally, patients with grade IIb and/or III injuries will need GI follow up for stricture and cancer screenings.

Case Followup:

The patient rinsed out his mouth with water. He developed drooling and chest pain. Lab work was obtained which demonstrated an anion-gap acidosis likely due to the sulphur ingestion. CXR was without pleural effusion or free air under the diaphragm. GI performed an urgent endoscopy which demonstrated Grade 2a lesions. Patient was observed in the hospital, started on a soft diet and a PPI. He was discharged on hospital day 2.

Clinical Pearls:

- Caustic injury to the aerodigestive tract can be caused by a variety of acidic or alkaline substances.

- A good history including the type of chemical ingested and why it was consumed is key to the diagnosis and management.

- Activated charcoal or gastric lavage are NOT indicated.

- Laboratory testing and imaging may be indicated based on physical exam and type of ingestion.

- EGD is indicated in intentional ingestions, patients demonstrating stridor, or unintentional ingestions with inability to tolerate PO after overnight observation.

- EGD should be performed within 24 hours but no later than 48 hours post ingestion.

- Supportive care is the mainstay of treatment, but steroids may benefit some patients post-EGD.

References:

- Wightman RS, Fulton JA. Caustics. In: Nelson LS, Howland M, Lewin NA, Smith SW, Goldfrank LR, Hoffman RS. eds. Goldfrank’s Toxicologic Emergencies, 11e. McGraw-Hill.

- Bouchard NC, Carter WA. Caustic Ingestions. In: Tintinalli JE, Stapczynski J, Ma O, Yealy DM, Meckler GD, Cline DM. eds. Tintinalli’s Emergency Medicine: A Comprehensive Study Guide, 8e. McGraw-Hill.; Accessed May 19, 2021.

- Cheng, H. T., Cheng, C. L., Lin, C. H., Tang, J. H., Chu, Y. Y., Liu, N. J., & Chen, P. C. (2008). Caustic ingestion in adults: the role of endoscopic classification in predicting outcome. BMC gastroenterology, 8(1), 1-7.

- Hoffman, Robert S., Michele M. Burns, and Sophie Gosselin. “Ingestion of caustic substances.” New England Journal of Medicine 382.18 (2020): 1739-1748.

- Zargar, Showkat Ali, et al. “The role of fiberoptic endoscopy in the management of corrosive ingestion and modified endoscopic classification of burns.” Gastrointestinal endoscopy 37.2 (1991): 165-169.

- Chirica, Mircea, et al. “Esophageal emergencies: WSES guidelines.” World journal of emergency surgery 14.1 (2019): 1-15.

- Boukthir, S., Fetni, I., Mrad, S. M., Mongalgi, M. A., Debbabi, A., & Barsaoui, S. (2004). High doses of steroids in the management of caustic esophageal burns in children. Archives de pediatrie: organe officiel de la Societe francaise de pediatrie, 11(1), 13-17.

- B. Çakal, E. Akbal, S. Köklü, A. Babalı, E. Koçak, A. Taş, Acute therapy with intravenous omeprazole on caustic esophageal injury: a prospective case series, Diseases of the Esophagus, Volume 26, Issue 1, 1 January 2013, Pages 22–26, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1442-2050.2011.01319.x