Evidence-Based Medicine Improves the Emergent Management of Peritonsillar Abscesses Using Point-of-Care Ultrasound

Take Home Points

- Since the publication of the randomized control trial by Costantino et al. that showed a benefit to using POCUS in the management of PTAs, EPs are more likely to use POCUS to help diagnose and treat PTAs at this institution.

- POCUS use appears to significantly increase EP chances for a successful PTA aspiration and significantly decrease ENT consults, ED LOS, and the need for return visits compared to the traditional landmark-based approach.

- Future Research: More research is needed to understand how POCUS can change PTA management when an abscess is NOT identified on ultrasound or when tonsillar cellulitis or phlegmonous changes are present. The secondary outcomes in this study (Take Home Point #2 above) need to be replicated at another institution.

Background

Peritonsillar abscesses (PTA) are the most common deep space infection of the neck. It can be difficult for a clinician to differentiate between a peritonsillar abscess and cellulitis upon physical examination alone. In fact, physical examination has limited sensitivity and specificity for a PTA. While complications (e.g. mediastinitis) are rare, they can be life-threatening, so it is important to recognize and treat this pathology early. We know that physical exam is not great for making this diagnosis. Traditional management involves landmark-based blind needle aspiration, but not surprisingly, this has a high false negative rate. We also don’t want to have to CT everyone’s neck. You have probably deduced that there must be a better way, and that it likely has something to do with point-of-care ultrasound (POCUS). PTA meet your match-POCUS.

POCUS has transformed the management of these pesky purulent collections in recent years. Prior studies have shown that POCUS helped improve diagnostic accuracy and increased the rates of successful aspiration of PTAs. Specifically, the randomized control trial by Costantino et al. published in 2012 demonstrated that ultrasound confirmed the diagnosis of PTA more often and led to more successful aspirations than a landmark-based technique. Additionally, the study revealed a lesser need for otolaryngology (ear, nose, and throat [ENT]) consultation and CT when ultrasound was used instead of the landmark-based approach. Note that this RCT was 28 patients and they used an intraoral US-assisted protocol. They also seemed to be evaluating it as a diagnostic test compared to drainage as a means for diagnosis.

The study at hand expands upon the existing literature on how POCUS can improve patient outcomes by increasing first attempt PTA drainage while reducing the need for ENT consultation and CT and decreasing the length of stay (LOS) and need for return visits. Management of PTAs is a skill that all EPs (emergency providers) need to be proficient in; accordingly, let POCUS help guide your needle to benefit you and your patient in the future.

We have touched on this topic a little on GEL in the past:

Prior US GEL from May 2020. A radiology performed transcervical US protocol for PTA seemed to shorten ED LOS in a pre/post study.

Question

Since the publication of the randomized control trial by Costantino et al., how has physician behavior changed with regard to using POCUS in the management of PTA?

Does EP use of POCUS increase the likelihood of successful PTA aspiration?

Does EP use of POCUS decrease the likelihood of ENT consultation, CT imaging, unscheduled emergency department (ED) return visits, and LOS?

Population

Inclusion Criteria

· > 18 years old

· Final diagnosis of PTA

Exclusion Criteria

· Peritonsillar cellulitis

· Phlegmonous changes

· CT performed prior to POCUS

· Transferred patient from an outside facility

Design

This study is a retrospective case control study at a single-center urban, academic emergency department.

✱In this post, the protocol we describe is from the initial 2012 paper, but wasn’t entirely detailed in this paper. See Scan (below) for how they did the ultrasounds.

Researchers queried the electronic health records for patients diagnosed with a PTA using ICD-9 diagnosis codes. Two cohorts of patients were studied. Cohort 1 and 2 included patients that presented to the ED with a PTA from 1/2007-1/2008 and 1/2013-12/2014, respectively.

A retrospective chart review and data abstraction were performed on patients with the diagnosis of a PTA between the established timeframes. Data was divided into two patient groups: 1) POCUS or 2) no POCUS (NUS) as part of the PTA management. The use of POCUS in PTA management prior to the publication of the randomized trial by Costantino et al. was compared to the POCUS usage after publication. Successful aspiration, need for advanced imaging, return ED visits within 7 days, and LOS were compared across the two groups.

Primary Outcomes:

· POCUS utilization between cohorts

Secondary Outcomes:

· Successful aspiration

· Frequency of specialty consultation

· Need for advanced imaging

· Unscheduled return visits within 1 week

· LOS (defined as length in time from initial EM provider presentation to final disposition)

Who did the ultrasounds?

PGY-1, -2, or -3 EM residents under the supervision of attending emergency medicine physicians performed the procedures. All emergency medicine physicians were credentialed in the core American College of Emergency Physician POCUS applications.

The Scan

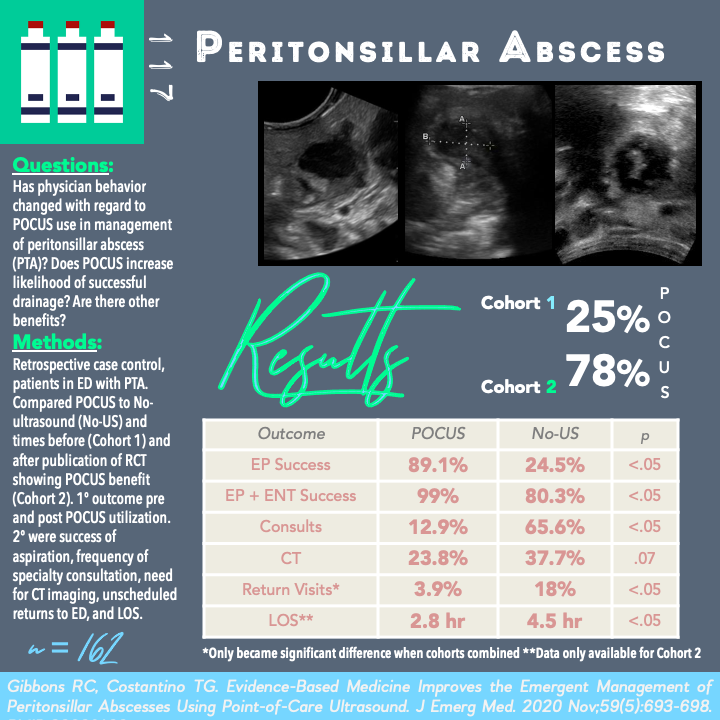

Endocavitary

POCUS was performed in patients with a clinical suspicion of PTA. If POCUS diagnosed a PTA, the EM resident aspirated the PTA under POCUS-guidance.

The POCUS-guidance protocol used was based on a previous protocol established by Costantino et al. Patients received both a topical and local anesthetic prior to the procedure. An 8-5 MHz intraoral, intracavitary transducer was used to identify the location of the PTA, as well as the carotid artery using color flow Doppler. An abscess was defined as a “distinct anechoic area or hypoechoic area in the posterior pharynx in the area of swelling.” The distances from the probe to the front of the abscess and to the carotid artery were measured.

All ultrasound studies were static meaning that the provider performed the ultrasound first, removed the probe, and then attempted needle aspiration. Aspiration was attempted using an 18-gauge needle attached to a 10-ml syringe. If the first attempt at aspiration failed, providers were permitted an additional two attempts.

Results

Primary Outcome – POCUS utilization between cohorts

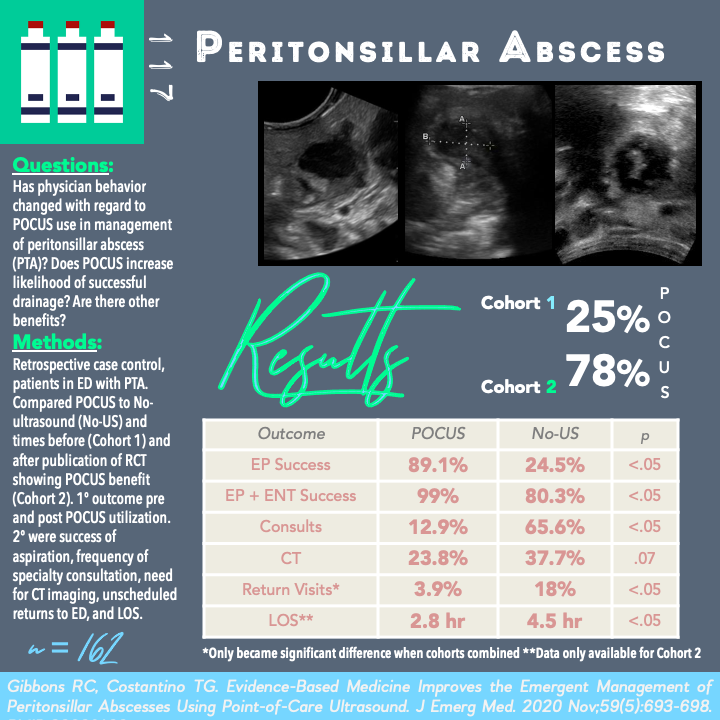

Cohort 1 – 25% → Cohort 2 – 78%

EP use of POCUS as a tool in the management of PTA has significantly increased from 25% to 78% (p< 0.0001, OR 0.09 [95% CI 0.04-.20]) since the publication of the results of the randomized trial of Costantino et al that validated the use of and demonstrated the benefit of POCUS in the management of PTAs.

Secondary Outcomes

Cohort I: N=48 patients (median age 33 years)

In summary: Improved successful aspirations by EP and a decreased need for ENT consultation were clinically significant outcomes between the POCUS vs No-Ultrasound (NUS) groups in Cohort I. There was no clinical significance between the overall success rate of drainage with ENT consult, CT usage, and return visits between groups in Cohort I. Of note, length of stay (LOS) data was not available for this cohort.

Cohort II: N=114 patients (median age 32 years)

In summary: Successful aspirations by EP alone and with ENT consultation, reduced rate of ENT consults, lower CT usage, and reduced average LOS in the ED were clinically significant between the POCUS vs NUS groups in Cohort II. Return visits were not clinically significant between groups in Cohort II.

Collective Data from Cohort I and Cohort II: N = 162

· 62.3% of patients had POCUS performed as part of their PTA management.

Successful aspiration by EP

- POCUS 89.1% vs NUS 24.5% (p<.0001, OR 25 [95% CI 10-59])

ED plus ENT successful aspiration

- POCUS 99% vs NUS 80.3% (p<.0001, OR 24 [95% CI 3-193])

ENT consultant rate

- POCUS 12.9% vs NUS 65.6% (p<.0001, OR .07 [95% CI .03-.17])

CT usage

- POCUS 23.8% vs NUS 37.7% (p=.07, OR .51 [95% CI 0.25-1.02])

Return visits✱

- POCUS 3.9 % vs NUS 18.0% (p=.004, OR .18 [95% CI .05-.61])

✱This is one outcome where it was not statistically significant in either of the two cohorts, but by pooling the data, now it is.

Overall, successful aspiration by EP, combined EP plus ENT success, the need for ENT consultations and return visits were clinically significant when data was combined between the two cohorts. CT usage was not clinically significant but there was a trend toward decreased CT usage in the POCUS group.

Strengths

Generalizable to an academic EM setting where most ED attendings are credentialed in ultrasound. Most ED attendings that supervised the exams were not EUS fellowship trained and had not performed more than 10 prior PTA POCUS scans.

The POCUS exam was performed by the same clinicians treating the patients.

Meaningful secondary outcomes to EPs included a reduction in length of stay and return visits.

Limitations

Single center study, Retrospective design, Convenience sample

Potential for selection bias. There may have been certain characteristics in those who received POCUS versus those who did not that would affect the outcomes.

Population was only patients with final diagnosis of PTA, which misses all of the patients in which it was suspected but ultimately did not have it (obviously the latter population is hard to identify retrospectively). Therefore, this data does not necessarily inform how ultrasound changes management in patients with tonsillar cellulitis or phlegmonous changes.

Endocavitary probes may not be accessible at all institutions. These authors did not assess the transcutaneous (aka submandibular) approach which has certain benefits.

This study may not be as generalizable to community EM practice where POCUS knowledge and support may not be as robust as in an academic practice environment. The size of cohort I is substantially smaller than Cohort II, biasing towards more recent practices at this institution.

The study did not address how accurate POCUS was compared to gold-standard CT (for cases when CT was obtained after a failed POCUS-attempt).

Same authors that published the original randomized trial. This decreases external validity (especially for the primary outcome of practice change). It would be beneficial to see a similar study performed at another institution.

Discussion

Diagnostic vs Therapeutic benefits. The first study (RCT) seemed to be touting the diagnostic benefits of using POCUS. It is not hard to believe that using an imaging study is better than using no imaging study. Now – if we have already made the diagnosis (either by physical exam, POCUS, CT), the next question should be – does using POCUS increase the therapeutic success? The problem is that this study blends those questions into one. It is hard to say from this retrospective vantage if POCUS was being used to make the diagnosis, or if the diagnosis was obvious and POCUS helped to guide the procedure. Ultimately, POCUS can be very useful in doing both; however, from a research question standpoint, it makes it a little harder to interpret the data not knowing exactly what question they were asking when they did the ultrasound. The population could be quite heterogenous if some patients had an unclear diagnosis and others had an obvious diagnosis. It would have been

great to see a comparison of the patient characteristics between the POCUS and non-ultrasound groups, and also a comparison of those characteristics between Cohorts 1 and 2.

For community EPs in particular, using ultrasound may save your patient the need to be transferred to an outside hospital for ENT consult. More studies on outcomes of using a submandibular approach to drain a PTA may be helpful to EPs without access to intracavitary probes. Furthermore, it would be beneficial to investigate how ultrasound changed the management of and affected the outcomes in patients with no abscess identified on ultrasound but with a diagnosis of tonsillar cellulitis or phlegmonous changes. Overall, this paper contributes to the existing literature showing that ultrasound can be an invaluable tool to EPs managing PTAs and lead to improved patient outcomes in many cases.

Summary

This study demonstrated that EPs have changed their approach to management of PTAs since the paper published by Constantino et al. EPs are more likely to use POCUS as a tool to assist them with the diagnosis and treatment of PTAs. This paper was able to demonstrate that the POCUS first approach can lessen the need for ENT consultations, reduce return visits, and decrease LOS in the ED. Overall, these patients tended to receive less CT scans compared to traditional management.

Take Home Points

- Since the publication of the randomized control trial by Costantino et al. that showed a benefit to using POCUS in the management of PTAs, EPs are more likely to use POCUS to help diagnose and treat PTAs at this institution.

- POCUS use appears to significantly increase EP chances for a successful PTA aspiration and significantly decrease ENT consults, ED LOS, and the need for return visits compared to the traditional landmark-based approach.

- Future Research: More research is needed to understand how POCUS can change PTA management when an abscess is NOT identified on ultrasound or when tonsillar cellulitis or phlegmonous changes are present. The secondary outcomes in this study (Take Home Point #2 above) need to be replicated at another institution.

More Great FOAMed on This Topic

Our Score

Expert Reviewer for this Post

Christina Wilson, MD @cnwilsono

Christina is an emergency medicine physician and the Emergency Ultrasound Fellowship Director at Maine Medical Center.

Reviewer’s Comments

It is encouraging to see evidence that emergency physicians (EPs) change clinical practice in response to new evidence (especially when it involves using more ultrasound!); however, this paper left me wondering how this physician group went from 25% POCUS use for PTA up to 78%. Are the authors implying that just knowing that POCUS for PTA works and benefits patients is enough for EPs to learn the skill and change their practice independently or was there an educational intervention, curriculum change, or new policy/pathway introduced? As an ultrasound educator, I would love to know.